Black Twitter has always been that special place in the Twitterverse where African Americans have congregated to discuss issues germane to the black experience, but recent events in Ferguson, Mo., have solidified it as something more: a vital 24-hour news source.

After unarmed 18-year-olf Michael Brown was shot dead by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson on Aug. 9, national media began to parachute in to the St. Louis suburb. Right behind them (or some would argue ahead of them), black bloggers and activists were online, critiquing the stories and tweets of reporters on the ground for cultural accuracy. In any story involving a black young person killed by a white one, the subject of race tends to lead the narrative.

Many critics believed from the onset that media coverage of the unrest – especially the looting that followed – unfairly described the residents' grievances. Nikole Hannah-Jones at Essence wrote that initial coverage of the rioting overshawdowed the fact that a teenager's life was taken.

"As a journalist, I get it," she wrote. "The images of the rioting were gripping. But coverage of the riots should not overshadow the cause of the riots. The real story has taken a backseat to the sensational. A young Black man lost his life in a confrontation with police under very controversial circumstances. Ferguson is policed by a nearly all-White police force. This context has been missing in too many of these stories. And in the eyes of many people commenting on social media, this type of reporting has rendered the destruction of property more important than the destruction of Black life."

To counter that narrative, one Twitter user and activist who goes by the handle @Awkward_Duck tweeted a photo of young men in Ferguson protecting a store from looters with the caption, "What the news won't show you is protestors standing in front of stores, hands up, blocking looters from getting in. #ferguson."

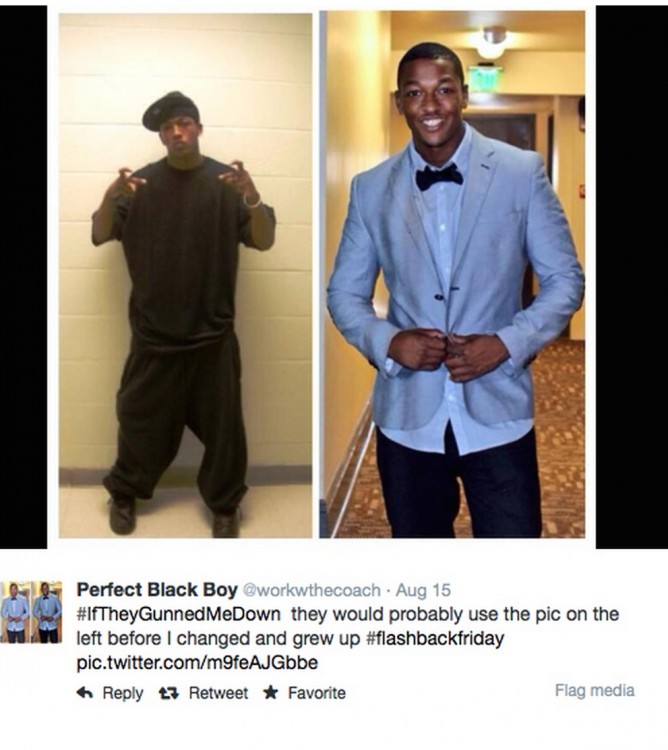

After several media outlets used photos from Brown's Facebook page showing him posed in a less than dignified matter, African Americans on Twitter started the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown. Users combined photos of themselves in one image – one photo of themselves dressed in college graduation wear, for example, and the other of themselves flashing what could be perceived as gang signs or some other pose that could be perceived as negative.

Some of the captions read, "#IfTheyGunnedMeDown which pic would they use?" or, "#IfTheyGunnedMeDown they would probably use the pic on the left before I changed and grew up #flashbackfriday."

One of the tweets was shared as many as 22,000 times. Other were retweeted thousands of times as well. The story behind the hastag would eventually make it on the front cover of the New York Times.

Kimberly C. Ellis, Ph.D, American and Africana Studies Scholar and Public Intellectual who is completing a book titled "The Bombastic Brilliance of Black Twitter," told AlterNet that the hastag played a very influential role in how the media covered Ferguson after it began trending.

"That set the precursor for the media and they had to think about how they were going to present Mike Brown," Ellis said, who goes by the handle "@drgoddess" on Twitter. "I honestly believe that #IfTheyGunnedMeDown prevented mainstream media from doing their usual lazy presentation on black youth in particular and black people in general."

To be sure, there are many reporters on the ground who are using their large platforms to provide nuanced coverage of Ferguson. Twitter-savvy reporters like Wesley Lowery, of the Washington Post, Joel D. Anderson, of BuzzFeed, Yamiche Alcindor, of USA TODAY, Ryan J. Reilly, of the Huffington Post, are some of them.

But independent bloggers on Twitter have begun blogging from Ferguson after their loyal audiences began raising funds to finance their living expenses.

Elon James White, CEO of "This Week In Blackness" with a following of more than 35,000 followers on Twitter, told AlterNet that he began reporting from Ferguson after his audience raised money for him and his team in less than 24 hours. During his first day in Ferguson, he said noticed how police were aggressively engaging peaceful protesters and that he documented much of it.

"I spoke with people directly to find out what was happening and it wasn't just about this incident," he said. "There is a history of issues and this was not being reported in the media at the time. But it was because I was able to come down and talk to people directly and find out exactly what was happening that I got to witness what was going on."

African-American blogger, Zellie Thomas, who blogs from Black Culture, told AlterNet that his Twitter followers also financed his travel to Ferguson after being unsatisfied with mainsteam coverage. "I think that a lot of people trust our news source more than the media," Thomas said. "Most of us are people of color and we already have good reputations online, so people trust our facts."

A lack of diversity impacts how media cover stories. Recent data reveal troubling numbers that show the lack of people of color in America's newsrooms. The Pew Research Center reports that "the number of black journalists working at U.S. daily newspapers has dropped 40% since 1997" and that "just 10% of the local TV news workforce was black in 2013, the most recent available data. That’s a decline from 2009, when the rate peaked at 12%."

One area where African Americans are the majority is in their use of Twitter – especially younger users. Forty percent of African Americans between the ages of 18-29 use Twitter, as conpared to just 28 percent of whites in the same age range, according to the Pew Reseach Internet Project. African Americans are also just as likely to own a cellphone; 96 percent own one, with 56 percent of that number using a smartphone.

As far as when #BlackTwitter first appeared, no one is exactly sure and no one person has been credited for coining the phrase to describe the set of communities, with or without the hashtag. The name grew on people organically and they began vacillating between #NegroTwitter and #BlackTwitter around 2009-2010, Ellis said. She, for example, used, "The Twittuh," to describe the community of African American users active on the platform.

"There was no particular need for users to label the community, as blacks who used Twitter regularly already interacted with one another and did not need a hashtag to centralize their activity," she said. "But #BlackTwitter organically became popular and partly in response to mainstream media, the name took on a life of its own."

Sherri Williams, an educator at Syracuse University and former journalist, told AlterNet that social media and mobile technolgy puts storytelling power in the hands of everyday people, empowering them to add cultural nuance to stories about their communities that many newsrooms aren't always able to accomplish because of their dearth of diversity. While Williams believes diversity across the board is needed in newsrooms – economic, sexual orientation, racial, etc – she says the Michael Brown story is an especially vital time to have people of color on the ground to cover what is happening in Ferguson.

"In a case like this, it's really important for mainstream newsrooms to have people of color on staff because there is a lived experience and a knowledge that they have, insider information and personal experiences with law enformement that others outside of the community don't have," she said.

"That information is helpful with understanding the community that they are reporting on. If you have someone who grew up in an area and having a lifestyle of privilege where they've only had friendly encounters with law enforcement, this kind of outrage that the community is experiencing would be totally foreign to them."

But Ellis says that the Afican-Amercian community that comprises #BlackTwitter are filling in the gap and doing a very good job of serving as its own newsroom. "Chuck D would say, 'We're the Black CNN.' Well, #BlackTwitter is the new CNN," she said. "In fact, we're better than them."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments