Conversations about fracking for natural gas and shale oil typically orient toward one of two poles: either it is an energy and economic godsend that demands to be exploited, or it is a social and environmental catastrophe that cannot be considered.

In either view it is rarely understood just what a marvel the practice itself is. A look at the engineering, technology, and geoscience behind high-volume hydrofracturing, or fracking, shows it to be an astonishing materialization of human desire, intention and ingenuity. It also reveals the practice to be an agent of slow violence.

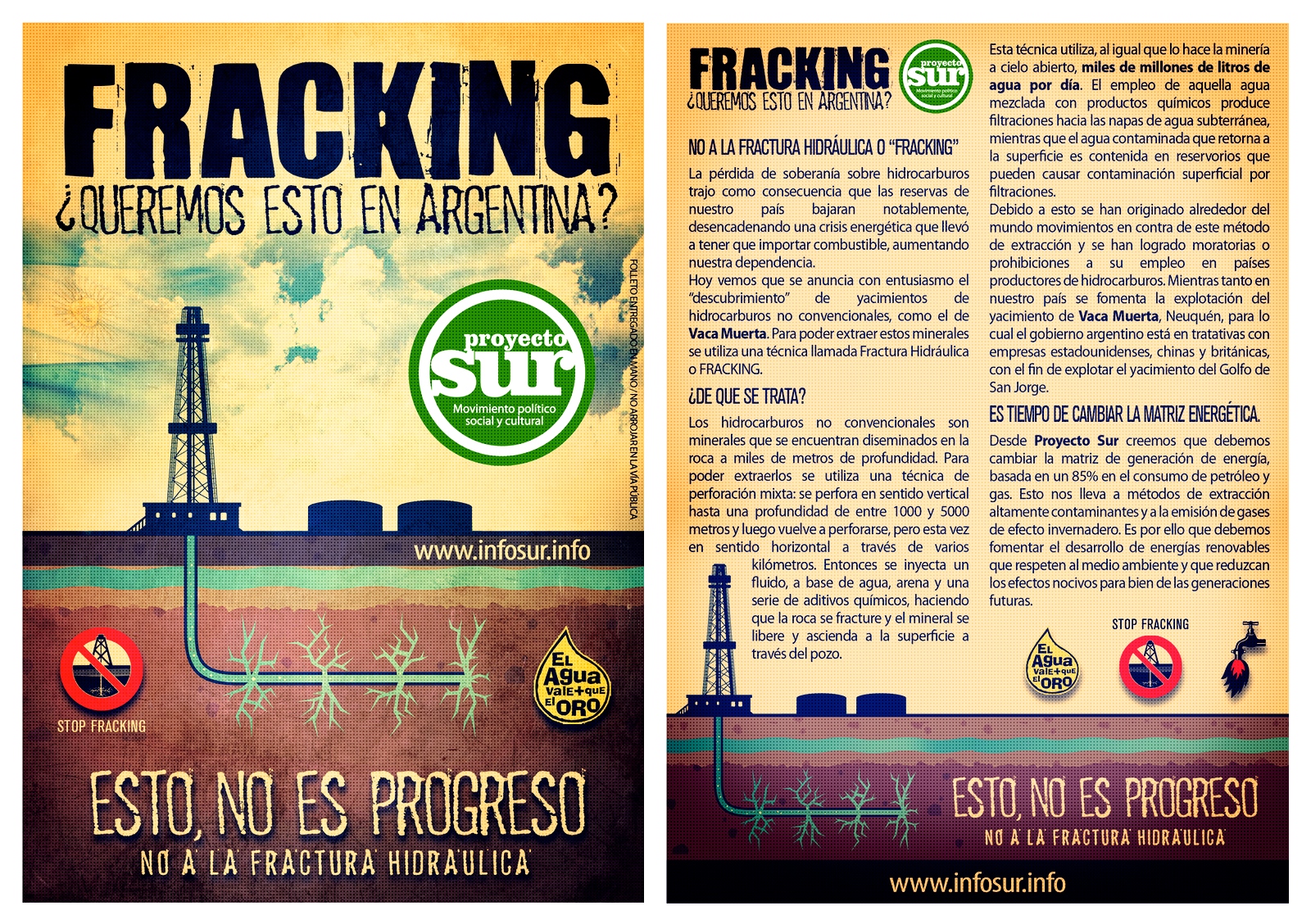

The ability to precisely drill down thousands of feet, change directions through heterogeneous sedimentary rock formed millions of years ago and fracture specific types of shale with powerful blasts of pressurized fluids in order to release billions of tiny, disparate bubbles of gas and collect it in a steel pipe is remarkable. And the extensive coordination and logistics needed to organize the various domains of expertise from geotechnics to drilling to wastewater disposal to cement contractors is equally awe-inducing.

This technological wonder, brought about through great effort and ingenuity, are all the more remarkable given fracking’s many unknowns. These include the exact structure and direction of the preexisting shale fractures or the long-term durability of steel and concrete structures thousands of feet below ground in rock that has just been fractured and is meant to cap spent wells. They also include the behavior and ethics of myriad contractors and hired hands spread out across a fracking basin who are responsible for properly disposing of the thousands of gallons of hazardous wastewater produced by drilling a well.

Many similarly spectacular and terrible efforts of the 20th century were imminently visible - think of the space flights, the Hoover Dam, the Golden Gate Bridge, but also the Love Canal, the Cuyahoga River Fire and the Dust Bowl. These objects and events lent themselves to representation in popular media. They were visually incredible, and spawned much heated public discourse. By contrast, many of the potentials, effects, and ramifications of fracking are difficult to represent in popular media. They operate on long time scales or under the earth’s surface, and their deleterious effects are often not immediate or visually impressive.

The spectacular organization and engineering at work in these efforts makes accidents, spills, and contamination a fact- certain to happen given enough time. While this would never be admitted in the copy produced by petroleum companies or acquiescent governments, pipes leak, concrete crumbles, contractors want to save on disposal fees or get home early on Friday. And the scope and scale of these long-term effects are often exacerbated in Argentina, the United States, and other countries in the Americas where regulation and governmental oversight by agencies like the U.S.Environmental Protection Agency or the Argentina COFEMA (Federal Environmental Council) is made more difficult by huge expanses of rural lands with small populations and relatively weak federal governments.

The contamination of critical aquifers, extreme compaction of huge swaths of agriculturally productive or ecologically healthy soils, the rerouting of capital investment and human ingenuity away from the design and development of renewable energy technologies, and the rapid expansion and social disarray that historically result in boom-towns built around resource mining and extraction are all very real possibilities in shale plays around the world.

Whereas the Hoover Dam, or the flaming surface of the Cuyahoga River in 1969 Cleveland (a spectacular disaster that galvanized public opinion and policy-making and lead to the creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency after catching the attention of Time Magazine) are immediate and spectacular, compacted soil and contaminated aquifers don't make headlines.

The perception and representation of violence shapes the public discourse on environmental and industrial issues. It was violence at the demonstrations over the Vaca Muerta agreements in Neuquén that attracted so much media attention. However, this limited conception of violence makes it difficult to represent and understand long-term negative effects of an operation like fracking. As a result, much of the conversation ends up either extolling the immediately visible benefits such as new jobs or lower energy prices, or making broad environmental justice arguments that are difficult to quantify or verify in a short time-span.

Recognizing this issue, Rob Nixon offers up the concept of slow violence as a way to understand these issues: Violence is customarily conceived as an event or action this is immediate in time, explosive and spectacular in space, and as erupting into instant sensational visibility. We need to engage a different kind of violence, a violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales. In doing so, we also need to engage the representational, narrative, and strategic challenges posed by the relative invisibility of slow violence.

By simply combining the visceral connotations of violence with the idea of slowness, Nixon puts a finger on the central misalignment in the contemporary fracking discussion: the immediate and measurable effects tend to be somewhat beneficial, while the longer term effects that are ambiguous and difficult to quantify tend to be bad. And while the timeline of the beneficial effects is measured in months and years, and aligns with the quarterly earnings reports of corporations and the election cycles of local politicians, the timeline of the deleterious effects is measured in decades and generations and seems impossible to properly weigh when unemployment and energy prices are rising now.

The Vaca Muerta was in the news last August because of the demonstrations and violent official response in Neuquén after the government signed lease agreements that opened the door for that investment and exploitation. The demonstrators intended to prevent those agreements from being signed, so that foreign multinational petroleum corporations, including Chevron, could not begin exploring for and exploiting unconventional oil and natural gas in the Vaca Muerta shale play. The violence resulted in injury to six police officers and twenty-five demonstrators. The agreements were signed on August 28.

Demonstrations in Neuquén, and the violence used to suppress them, received much attention. While the powerful forces pushing for fracking in this zone make its eventual realization seem certain, corporations, federal and local governments, indigenous communities and local citizen groups continue to openly jostle for influence over the shape that industrial extraction operations will take in Neuquén.

This ambiguity makes the existence, and significance, of long-term effects such as groundwater contamination difficult to represent. Slow violence is an extensive effect, something that is massively distributed in space and time and difficult to understand as discrete moments, events, or objects. In [my previous article on the Vaca Muerta]((http://www.occupy.com/article/invading-vaca-muerta-brief-summary-recent-...) I mentioned that the ability to understand and operate on multiple scales and fronts at once is essential in a fracking situation. Local communities, including those in Neuquén and my own here in central New York, need to be able to weigh the short-term and the long-term, the intensive and the extensive. Nixon's idea of slow violence offers one way to do that. This sort of hybrid thinking promises the possibility of a third path in the fracking discussion, a way of operating that is pragmatic and contextually-driven.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments