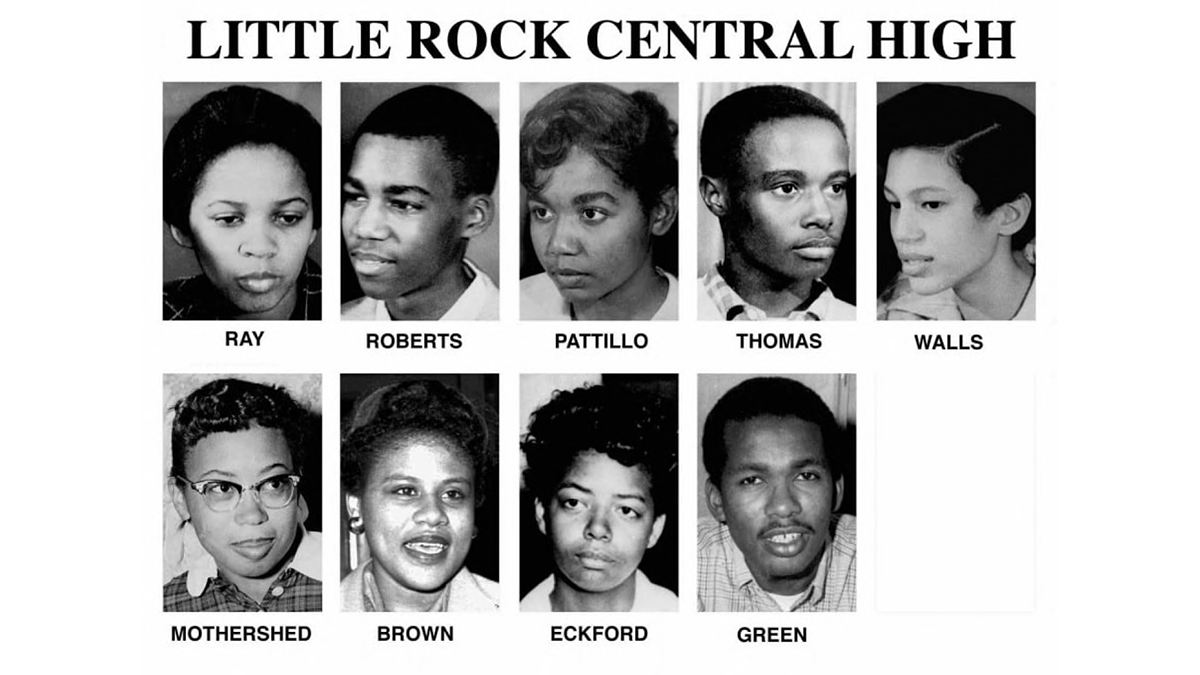

It was a moment of turmoil, when a school became a lightning rod for debates about American values and the Constitution. At the center of it all was a clutch of students, their teenage faces beamed across the country by television cameras. But no sooner had they emerged as heroes than they were branded as phonies.

The year was 1957.

Sixty-one years before teens at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., would survive a mass shooting only to be labeled “crisis actors,” the nine African American teens who braved racist crowds to enroll in Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas were also accused of being impostors.

False rumors that the Little Rock Nine were paid protesters even forced the NAACP to issue a statement condemning the stories as “pure propaganda.” The students were not, in fact, “imported” from the North, said the NAACP’s Clarence A. Laws, but rather the children of local residents, including veterans.

When Princeton history professor Kevin M. Kruse pointed out the parallel between Parkland and Little Rock earlier this week, his tweet went viral.

“It’s funny,” Kruse told The Washington Post on Thursday. “I’m teaching a class right now that does deep dives into three historical moments as a way to teach students how to use documents, and the first one we’re doing is on Little Rock. … So when the ‘these students must be paid’ thing came up in the news, it took me a day and then I was like, wait a minute, I just read about this.”

But the practice of dismissing witnesses to major historical events as mere paid actors goes back much further than the Little Rock Nine.

“It’s a theme that crops up throughout civil rights history,” said Kruse. “Back then, it was an assumption that African Americans in the South couldn’t possibly be upset. They must have been stirred up from the outside, either paid to do this or inspired to do this by propaganda. They couldn’t have come up with this on their own.

“I think this is what we see in the Parkland case today,” he added. “There’s a belief that somehow these 17- or 18-year-olds who witnessed a school shooting … who saw their friends die, somehow could not have been motivated to respond to that on their own, that they would need some sort of outside direction for that protest to take shape.”

The crisis actor slur dates back to shortly after the Civil War, when former slaves who testified before Congress were slandered by Southern politicians as stooges paid to lie about their experiences, according to Boston College history professor Heather Cox Richardson.

In December 1865, six months after the war’s end, Congress convened a special Joint Committee on Reconstruction to “inquire into the condition of the States which formed the so-called Confederate States of America, and report whether they, or any of them, are entitled to be represented in either house of Congress.”

The future of the country was at stake. Northerners feared that full representation for freed slaves could, ironically, hand control of Congress over to many of the same Southern politicians who had led secession.

The committee took testimony from 144 witnesses, including former slaves who described in detail the decades of horrors they had endured.

“But Congress figures out they have a problem because many African Americans can’t afford to come to Washington and they can’t afford to take time away from work to testify, so they begin to pay the people testifying before [the committee] a per diem and they pay their travel expenses,” said Richardson, who has written several books on Reconstruction.

“Democrats look at this and say, ‘This is outrageous. You are paying them to lie to keep yourselves in power and to force policies down our throats that we hate,’ ” she said. “And you literally get the argument that these people are lying about what happened because they are getting a payoff.”

The same thing happened in the 1870s when African Americans again testified before Congress about the Ku Klux Klan.

“Hundreds of black women and men played a remarkable role, coming forward to testify during the hearings,” Kansas University history professor Shawn Leigh Alexander wrote. “Democratic committee members attempted to discredit their testimony, equating the two-dollar-a-day allowance that witnesses received to bribery and accusing local Republicans of coaching them.”

When Reconstruction gave way to lynch mobs and Jim Crow laws, Southern whites no longer needed to discredit African American witnesses, Richardson said.

But with the rise of the civil rights movement half a century later, black voices were again shouted down with baseless claims. In 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. was charged with perjury for supposedly hiding thousands of dollars of donations from Northern supporters, Kruse pointed out. King beat the charges, which were politically motivated.

When three civil rights workers went missing in Philadelphia, Miss., in the summer of 1964, “segregationists said, ‘Oh, this is all a hoax. They were paid to do this, this was their plan all along, they want to draw sympathy to the plight of blacks down here,” Kruse said. “They said they were off laughing it up in Communist Cuba.”

In fact, the three men had been murdered by the Klan.

“There is a constant theme that anyone advocating for full equality, for equal rights for African Americans in the South in the ’50s and ’60s can’t be doing it because they sincerely believe in that, but because they’ve been put up to it,” Kruse said. “Because if [segregationists] accept that it’s African Americans from the South demanding this change, then it exposes as a lie their insistence that race relations were good, that blacks and whites were happy, that everyone locally was fine with this arrangement, which was the fiction that they told themselves for generations.”

Both historians saw parallels between the dismissal of civil rights activists in the past and the undermining of outraged Parkland students today.

“It’s the same idea,” Richardson said. “That anybody who doesn’t agree with establishment politics must have no agency, be corrupt or not understand what they are doing.”

“The motivations then were obviously driven by race,” Kruse said. “I don’t think that’s a factor here. What they have in common, though, was a belief that these people protesting could not be protesting on their own.”

Whether fueled by the Internet or Trump’s frequent “fake news” allegations or the president’s own tenuous relationship with truth, crisis actor conspiracy theories — which have dogged everything from the 1969 moon landing to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks to the 2012 slaughter of first graders at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. — are being embraced by an ever growing number of people, the historians agreed.

According to Kate Starbird, a University of Washington professor who runs a lab that tracks the spread of online rumors after disasters, these conspiracies are now amplified by websites in the United States and overseas.

“The goal seems to be to want to undermine the collective response to tragedy,” she told The Post.

With his tweet, Kruse said he hoped to provoke discussion over why people would try to silence students today.

“Somebody responded in a tweet, ‘This is why we have historians,'” he said. “It’s not the only reason, but that’s why we’re here: to try and draw these connections between the past and the present.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments