Thanks for Your Input, Governor Christie.

Days after Phil Murphy’s call for a publicly-owned Bank of New Jersey sent shockwaves across state and national media, the proposal received an unexpected favor: Governor Chris Christie attacked it, saying the bank itself would eventually need to be bailed out and invoking the common trope that government bureaucrats shouldn’t be running the banks.

Murphy, a Democrat and the only declared candidate for New Jersey governor (the election is next year), quickly had his campaign team respond: “Given Chris Christie’s nine credit downgrades, lagging economic growth, budget shortfalls built on putting politics before families, broken promises, and subservience to Donald Trump, we’ll consider the source.”

When fallen governors attack you with stale anti-regulatory arguments, you’re probably on the right side of history. But Murphy could also have responded by mentioning Christie’s addiction to toxic debt and gargantuan secret fees paid to Wall Street firms to mismanage the state’s pension funds – the very kind of financial apocalypse public banks aim to solve. Under Christie, the state’s pension fund management fees went from $141 million in 2010 to $600 million in 2014. That’s about $1.6 million per day. In 2015, they’d grown to a staggering $720 million.

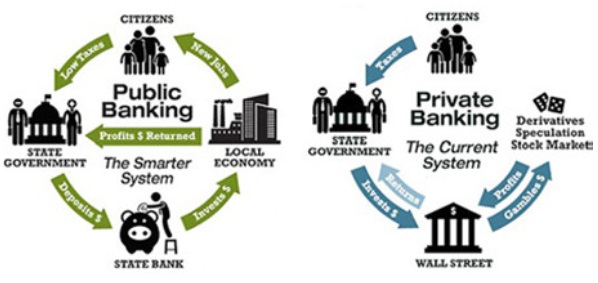

New Jersey has long been a testing ground for nearby Wall Street’s extractive banking practices. Like Pennsylvania and New York itself, New Jersey communities are besieged by city and county debt and fees. Public banks would serve most governmental financial needs, managing money in ways that would meet the three most important criteria for how banks should handle public money: minimizing risk exposure, ensuring liquidity and optimizing earnings. Wall Street has failed miserably at the first two, offsetting any success that would otherwise come of the third. Wall Street exposes governments to devastating risk and fails to lend adequate credit even in good times. Cities and people have died, schools closed, bridges crumbled, as a result.

Against this backdrop, and smoldering New Jersey political and economic realities, Murphy called Christie’s economic thinking “outdated,” and “a zero-sum economy where some are able to succeed only because others have been left by the wayside.” New Jersey, he said, should establish a North Dakota-style public bank, providing low-interest financing to small businesses, college students, and local governments.

Class Traitors and Public Banks

Murphy, a former Goldman Sachs executive, has jumped from the predatory ship and joined the ranks of the robbed and maltreated. Like Robin Hood, he’s a rogue nobleman, but unlike Robin Hood, who merely redistributed wealth, Murphy knows a public bank will create wealth from the ground up.

Why would a former Goldman Sachs executive embrace public banking? It’s not unprecedented: Nomi Prins, a biting critic of Wall Street and a fan of public banking, served in upper management at both Goldman Sachs and Bear Sterns before deciding they needed to be destroyed. Like the colonial elite who became enmeshed in debts to Britain and so joined the American Revolution, some members of the ruling class are jumping ship, a phenomenon I’ve discussed with economist Richard Wolff a couple of times. Wolff told me he thinks Murphy “knows what shenanigans go on in big banks and investment houses like Goldman,” but that “as a Democrat, he cannot attack pensioners the way other, especially Republican governors have,” and that a public bank would, among other things, be “less politically costly” than letting pension plans burn.

Ellen Brown, author of Web of Debt and The Public Bank Solution and co-founder of the Public Banking Institute, told me that while she couldn’t guess Murphy’s motives, she was happy he crossed over to the other side. “Our biggest hurdle has always been that legislators don’t understand how banking works,” she said. “They don’t understand that banks don’t lend their deposits but actually create deposits when they make loans, and that they’re wasting a huge opportunity by giving their revenues away to Wall Street to leverage for that purpose. It takes a banker to understand why states should have their own banks!”

Of course, in order to truly jump off the finance capital ship, that banker also needs to know the difference between just and unjust economics. Otherwise, their corruptibility will bleed into the public banks they create or manage. Murphy has a progressive Democrats’ grasp of economic justice. He calls for an expanded earned income tax credit and $15 minimum wage, and investment in rail infrastructure. These are good beginnings, but if Murphy wants to walk even further from GoldmanThink, he could follow the lead of another east coast candidate, Joshua Harris, running for Mayor of Baltimore on a revolutionary economic platform, also based around public banking, but even more appropriate to 21st century economic realities than the Democratic Party’s economic platform.

Because once you no longer think predatory finance is good, and realize that money is a tool rather than the whole toolbox, the entirety of economics changes.

Grassroots Movements are Right About Public Banking

The Bank of North Dakota’s success is not hype. It’s not “you can make statistics say anything.” BND has carried North Dakota through recessions, financed flood and fire relief that New Jersey could have used in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, helped build schools and repair roads and bridges at miniscule interest rates, kept vital community banks in business throughout the state, and created successful student loan and farm credit programs. Contrary to the Wall Street Journal’s assertion in 2014 that North Dakota’s oil boom made BND successful, BND was successful long before the boom, and helped create the infrastructure that made the thriving oil economy possible. Although the state is now taking a hit because of the rapidly declining fossil fuel economy, North Dakota’s public bank could, if used wisely, greatly soften that impact and finance a post-carbon transition in the state.

Public banks keep communities financially healthy in hard times because their economic benefits run “countercyclical,” lending at low interest when private banks won’t lend even at high interest. Rather than competing with community banks, public banks help them with loans and regulatory compliance (North Dakota has more community banks per capita than any other state).

Most relevant to New Jersey, public banks break the dependence on risky Wall Street finance. If it weren’t occurring slowly, mostly legally, and mostly in the dark, Wall Street’s pillaging of public treasuries would be the most scandalous financial story of the last 50 years. A public bank in New Jersey would have saved the state over a billion dollars on pension fund fees alone.

None of these benefits guarantee economic justice by themselves. A state or local government might use a public bank to finance unsustainable or environmentally harmful practices like fracking or mountaintop coal removal. But because a public bank is a public utility, the will of the people, rather than Wall Street shareholders and executives, determines the mission and functions of the bank.

In fact, the will of the people is responsible for Phil Murphy’s revolutionary policy proposal. The Bank of North Dakota was created by popular organizing and mobilization a hundred years ago. In his championing of a Bank of New Jersey, Murphy has used the language of the movement – a result of organizations like Banking on New Jersey and my former colleagues at the Public Banking Institute tirelessly working the state, along with Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, New York, Delaware, Vermont and Maine, creating widespread public banking consciousness all along the east coast.

Murphy is the highest profile political figure to raise the public banking mantle in the region. Hopefully he won’t be the last. The right combination of wealthy class traitors and local working class activists could create the space for a new era in sustainable economic justice. Public banks aren’t a panacea, but they’re a vital first step in giving control of financial decision-making back to communities.

A former board member and research consultant for the Public Banking Institute, Matt Stannard is policy director of Commonomics USA, an organization providing policy support for public banks and other economic democracy measures.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Matt Stannard replied on

Commonomics USA

Visit commonomicsusa.org

Ira Dember replied on

State-owned New Jersey public bank

Thanks for this excellent piece on public banking and its potential to serve NJ's public interest in unprecedented ways (unprecedented outside North Dakota, which already has a state-owned bank).

Chris Christie did NJ gubernatorial candidate Phil Murphy a favor by attacking him on public banking, focusing a welcome spotlight on this important issue. NJ.com's original report on Murphy proposing a New Jersey state-owned bank sparked 157 comments. But Christie's attack drew 270. Thank you, Gov. Christie!

The irony: North Dakota is one of the deepest red states, yet its public bank is one of ND's most popular institutions.

Regardless of who wins the NJ governorship next year, everyone should demand a clean, efficient, state-owned Bank of New Jersey as Phil Murphy has boldly proposed.

NJ taxpayers and businesses have been deprived of this public-interest economic engine long enough. New Jersey should seek to replicate North Dakota's public banking success.