In February of 1960, four young black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat down at a whites-only Woolworths lunch counter and demanded to be served. The sit-in grew to 20 people the next day, and 300 the following day, eventually attracting over 1,000. After that, sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters were happening nationwide. A few years later, the movement for civil rights that began with Rosa Parks’s defiant action on a Montgomery bus and carried over into lunch counters eventually resulted in the end of state-sponsored segregation.

Today, a new civil rights movement is emerging that begs for a successful example like this on which to model itself. The #BlackLivesMatter protests that swept hundreds of U.S. cities after the Michael Brown and Eric Garner grand jury decisions revealed a large segment of the country that wants to engage in a movement for social change. But after the street demonstrations dissipated, many on social media questioned whether there was a grand strategy to achieve the movement’s ultimate demands of criminal justice reform and police accountability.

Perhaps now we're discovering our answer. As North Carolina spawned the lunch counter sit-ins that put the Civil Rights movement directly in the faces of ordinary Americans 55 years ago, the state is also giving America an effective model for social justice organizing in today’s society – the Forward Together movement.

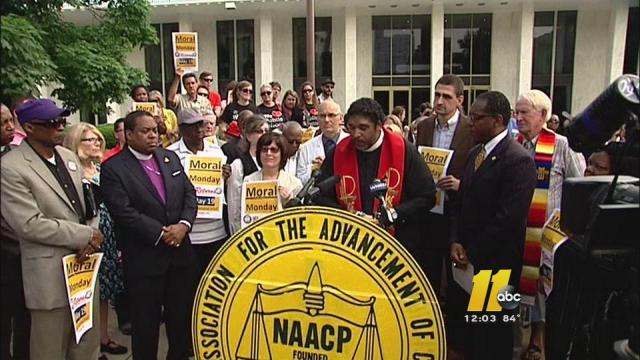

“’Black Lives Matter’ is not just a cry for black lives,” said Reverend William Barber II, president of the North Carolina NAACP and author of the book Forward Together. “The message is, if my life doesn’t matter, then nobody’s life matters. These same people ignoring the criminal justice system are the same ones ignoring the need for education funding and the need for voting rights. It’s not black-exclusive, it’s a statement that we are all one nation, and all of our lives matter.”

Reverend Barber, who has become the face of North Carolina's burgeoning social justice movement, believes America is “in the embryonic stages of a third reconstruction.” He cites the first reconstruction that began after the Civil War; the second one that began after the death of Emmitt Till and Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on the bus as a direct response to Till’s murder, and today’s third reconstruction that may have potentially began after the killers of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner walked free.

“Movements don’t come from the top down, they come from the bottom up. Nobody flies in and starts a sit-in movement with college freshmen, like the ones at that lunch counter in Greensboro,” Rev. Barber said during an in-depth interview with Occupy.com earlier this month. “Dr. King said, go back to Mississippi, don’t go to Washington. He said to build state-based movements from the bottom up.”

As I wrote in the previous installment of this series, the Forward Together movement, known in North Carolina as the Historic Thousands on Jones Street (HKonJ) coalition, brings together more than 170 state-based organizations under a 14-point agenda covering economic, environmental, racial, educational, voting, housing, and LGBT justice. HKonJ recently mobilized 30,000 people for this agenda outside the North Carolina General Assembly building in Raleigh on Feb. 14. Rev. Barber says Forward Together’s “deeply constitutional, deeply moral” movement is one that is rooted in the organizing traditions of the Civil Rights movement.

“Dr. King didn’t just organize in churches. He organized in pool halls. He went to disc jockeys on the radio, who had the same kind of reach then that social media has now. He went to hair salons, beauty shops,” Barber said.

Just as Martin Luther King’s movement organized for black Americans to have the right to vote without facing discriminatory barriers like poll taxes, Reverend Barber’s movement is organizing for those voting rights to remain intact. Forward Together won an injunction in the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals against North Carolina’s draconian voter suppression law, and is taking it to trial in July. Reverend Barber said the legislature’s attacks on voting came from a place of fear.

“Those who believe in the old white southern strategy recognize that when everybody comes together, they can formulate a new electorate,” Barber said. “The only way to beat organized money is to have organized people.”

One example Barber cites in his praise for “organized people” comes from Hyde County, a mostly poor community in the far-eastern part of North Carolina, in 1968. Despite desegregation being the law of the land after Brown v. Board of Education, the courts left the details of how to desegregate to the states most responsible for segregation. As a result, desegregation hadn’t reached places like Hyde County, North Carolina. County officials who were being forced to integrate their school systems simply closed down the black schools, erasing their names, mascots and traditions from history, forcing black students to assimilate. After months of sustained protests, the federal government finally intervened in favor of the protesters.

“In 1968, they stayed out of school for months, and shut the whole system down. They drained all the federal money out of the school system,” Rev. Barber explained. “They marched all the way from Hyde County to Raleigh, knowing that while they didn’t have the media, they had the power.”

Rev. Barber believes that for the new civil rights movement to achieve its demands, it must dedicate the time and energy to build a broad, youth-led, state-based movement, and escalate its tactics if demands go unmet. However, Barber is quick to note that while shutting down the system is sometimes necessary, actions must remain nonviolent to maintain a moral high ground.

“Shutting it down and tearing it down is different,” Rev. Barber said. “Shutting it down is civil disobedience. And that is the act of refusing to participate until what is supposed to work on behalf of the people works properly. And saying you will be willing to be arrested to draw attention to the issue.”

Stay tuned for part III of this series, which explores how youth are leading the North Carolina movement and looks at how organizations elsewhere can bring in young people to engage as lead activists.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments