A Republican Resists Big Money

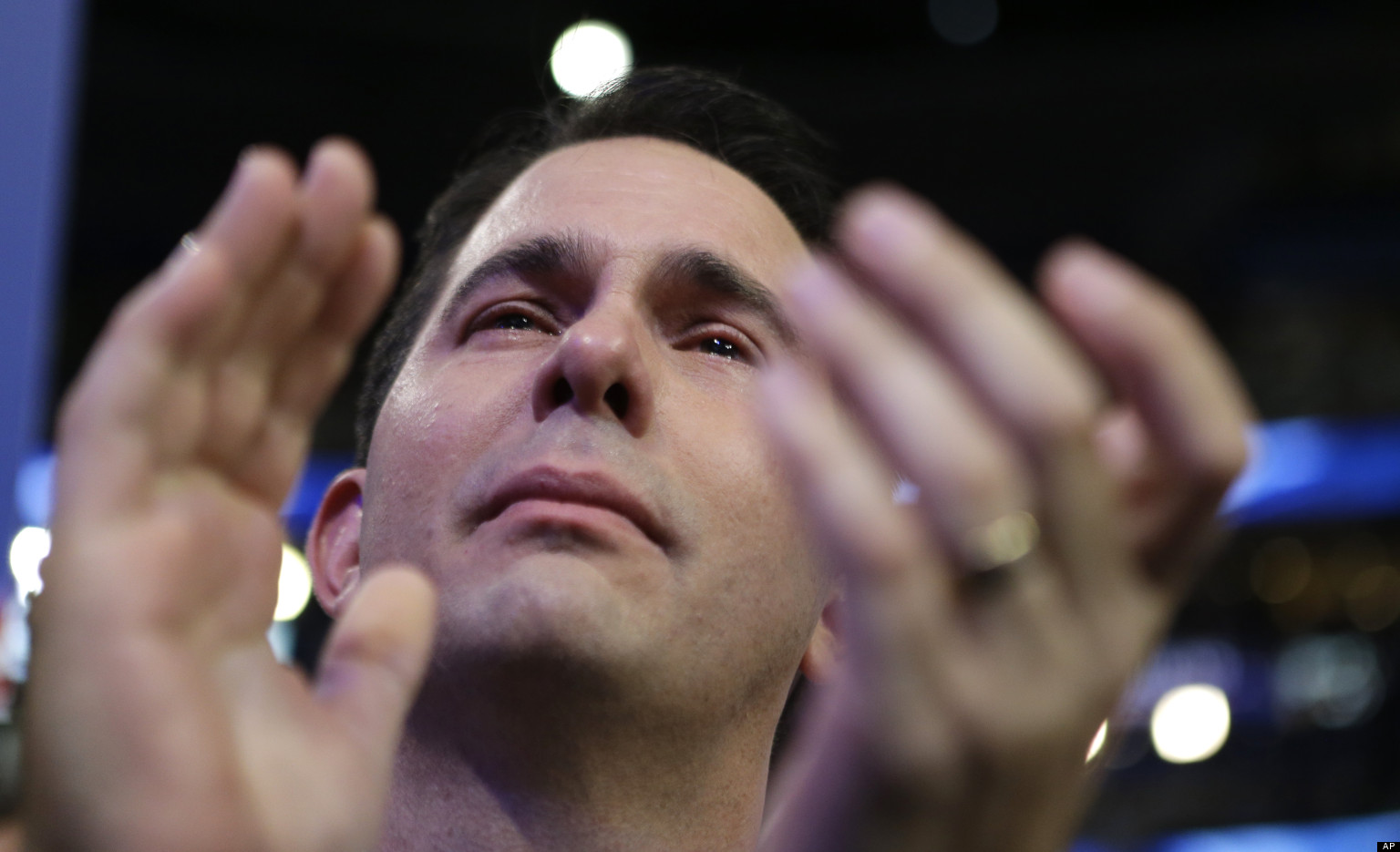

Dale Schultz, a Republican state senator from Richland Center, Wis., has held his seat for 23 years, and served in the state assembly for ten years before that. He’s stood for election 12 times. He was also the only Republican in the Senate to vote against Act 10, the infamous 2011 Wisconsin bill championed by Governor Scott Walker that crippled public sector unions’ organizing rights.

Now, Schultz has announced he won’t be seeking re-election, citing the rise of dark money in politics in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission ruling.

“The business of politics is changed, and I firmly believe that we are beginning in this country to look like a Russian-style oligarchy where a couple of dozen billionaires have basically bought the government,” Sen. Schultz candidly said in a recent, spontaneous interview in his office. “And you know what? I always thought the job of a representative in government was to represent the people.”

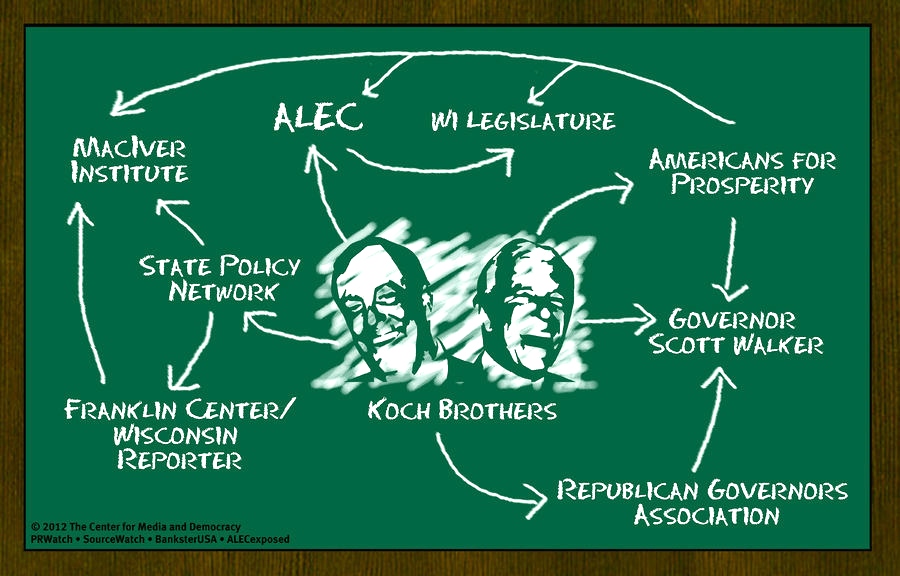

Schultz announced his retirement from his career as a legislator as he faces a primary challenge from the right by Rep. Howard Marklein, a Republican from Spring Green who has already raised over $100,000 for the next election – and is backed by the Koch Brothers-funded Americans for Prosperity, who made it a priority to oust Sen. Schultz.

“When you introduce a torrent – an ocean – of money into politics, all the elements are present to push towards more extremism in politics. And I think that sort of exploded with the decision in Citizens United,” said Schultz, who told me he had to raise $10,000 for his first Assembly race.

“As a Republican, I have always thought business should have access to the public square. I never thought anybody should be able to buy the public square, and that’s really about where we’re at right now.”

Schultz isn’t alone in his sentiments. US Senator Carl Levin (D-Michigan) recently said he would not seek re-election in 2014, simply because constantly fundraising for the next election got in the way of him doing his job. In his farewell address, John Kerry, the richest member of the U.S. Senate, urged his colleagues to address the “corrupting” influence of money in politics.

Schultz said it wasn’t a long time ago that $5 million would have seemed like a lot of money to spend in a gubernatorial election. However, in the 2011 recall elections against nine Wisconsin Republican senators, a whopping $44 million was spent by campaigns and outside groups.

“It puts good people on both sides of the aisle in a very difficult situation – because they know that if they try to represent their constituents, they’re going to be faced with a torrent of money by people who arrogantly believe that they will be able to buy enough space or time to drown out any other message but their own,” Schultz said.

“As long as [Citizens United] stands, we’ll see more money come into politics. We’ll come to see less discussion of the issues and more of the ads that everyone hates but still seems to have an impact.”

Corruption: Chief Obstacle of Progress

On January 22, during a frigid 18-mile march from Concord, New Hampshire to neighboring Manchester, I joined Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig, his organization Rootstrikers, and a new group calling itself the New Hampshire Rebellion, whose goal is to get political candidates to speak to what Lessig calls “the system of corruption in Washington.”

Lessig has talked at length about the influence of money in politics, and even gave a TED talk about how big money interests control the entire electoral process, leaving people without money without a seat at the table. Lessig said that today the average member of the U.S. Senate has to raise approximately $30,000 per week just to stay competitive.

“Members of Congress spend 30 to 70 percent of their time calling wealthy donors for campaign contributions instead of talking to their constituents,” Lessig said.

“The population of campaign contributors as opposed to the rest of the population is just 0.05 percent. This is equivalent to the number of people in the United States with the name Lester. So there’s the Lester primary, where the Lesters get to decide who people will get to vote for, and then there’s the primary for the other 99.95 percent of us.”

One of the marchers, 29-year-old Michael McCarthy, was a corpsman, or medic, for the Navy in Afghanistan, and spent time with Occupy Providence. He said before anything else can be done in Congress, Americans must first work to remove the influence of big money in the political process.

“Whether it’s immigration reform or the prison-industrial complex, it’s always these large money interests that are working against the interests of the greater populace,” McCarthy said. “This issue is so popular with such a broad section of people. It can pull people together from all sides.”

According to the numbers, McCarthy is onto something. A poll commissioned by the group Represent.Us found that 97 percent of Americans want to see anti-corruption legislation on the books. And according to that same poll, 82 percent of Democrats and 83 percent of Republicans agree that corruption should be reduced.

Nearly 80 percent of Independents say the candidate with the most money is most often the candidate that wins. And 51 percent of respondents openly believe that most politicians are corrupt.

A 'Citizens Movement' Against Money in Politics

Senator Schultz largely agrees with those sentiments, citing the recent Wisconsin GOP’s controversial gerrymandering of state legislative districts during the redistricting process. He wants to see non-partisan redistricting processes, where districts are drawn not by politicians looking to win elections, but by independent panels. Iowa, Arizona, Idaho and California have all moved to independent redistricting panels free of influence from state legislators – and are now seeing higher turnover rates for longtime incumbents as a result.

“People should be deeply concerned about [state legislators’] ability to draw districts that are bulletproof, where they get to pick their constituents rather than their constituents picking them. When that happens, you don’t have competitive elections,” Schultz said.

“When people vote for you, they understand you have a view of the world and that your actions may be colored accordingly. But, I think most people get a little bit angry when somebody gets elected to office and pretends they don’t exist. That’s where anger starts, and ultimately, a lack of civility.”

Schultz said once his term ends, he’ll continue working with his Senate colleague, Democrat Tim Cullen, on building what he calls a “citizens movement” to curb big money’s influence on the political process.

“I would hate to have this country look like Ukraine, or Egypt, but I think that’s where we’re headed as a country unless people stand up and say, ‘Enough is enough, we’re going to change this,’” Schultz said.

“There are all kinds of passionate, intelligent, motivated people who make a contribution to public life, community life, all across this country, every day. You don’t have to have Sen. or Rep. or any other abbreviation in front of your name to be a part of that.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments