By demanding the right to live, high school students across the country have articulated a concept of student rights as human rights.

The notion of student rights has largely been associated with the constitutional rights of schoolchildren during school hours. Human rights, on the other hand, has meant the responsibility of governments to provide basic human necessities such as receiving an education and having access to a home.

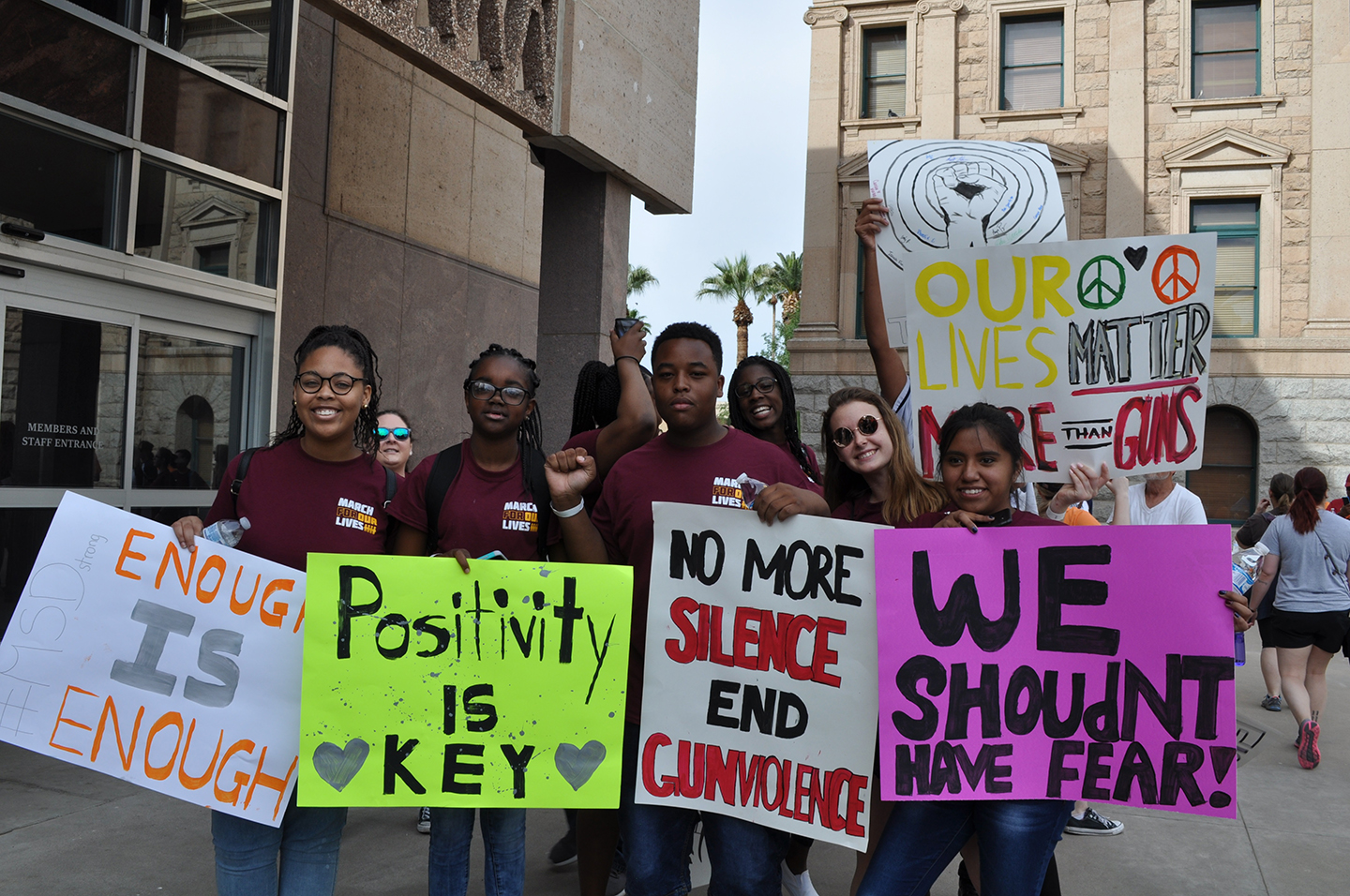

These provisions expand beyond the schoolhouse gate. Students advocating for these rights aren't necessarily new, but the Never Again movement and the March For Our Lives demonstration in Washington, DC, has elevated the concept of human rights for American high school students to the national level.

Students demanding human rights isn’t unprecedented. The high school student movement of the 1960s and 70s gave prominence to radical critiques of the American education system. Students saw themselves as constituting an oppressed group and believed schools were oppressive institutions because pupils lacked constitutional rights during school hours.

With the Vietnam War and civil rights movement in the background, students argued that in order to truly change society, high schools had to be made more egalitarian. Some high school student activists at the time called for human rights to ensure that every student upon graduating from school had access to a home, a decent job, and free college education. But these ideas, compared to student rights, never gained much traction. School districts were powerless in their ability to grant them.

High school students today are continuing the tradition of high school student radicalism. Certainly, the concerns of high school students today are different than they were 50 years ago. Rather than the Vietnam War and civil rights activists, the persistence of mass shootings has served as the catalyst for a national student movement.

On the other hand, they do share something in common with their predecessors: the belief that collective action can foster political change. Students of the 1960s created school-based, citywide, and even regional youth organizations to advocate for constitutional rights and change their schools and local communities. The National Student Walkout demonstrated students’ collective power to challenge the status quo and shame the inaction of lawmakers.

The quest for human rights has made the initiative for gun control a moral crusade. The idea that students have a right to live peacefully while in school and in their own communities addresses society’s failure to halt gun violence. Unquietly, this movement has now encompassed students from various socio-economic and racial backgrounds.

Activists have acknowledged the disproportionate effects of gun violence in communities of color. Students have confronted politicians with the question of whether they value their elected seat over the lives of children. This is quite different from student activist of the 60s and 70s, where students often addressed school boards rather than their elected representatives and advocated mostly for constitutional rights and curriculum reform. Rarely did students form meaningful interracial coalitions.

High school students are fighting an uphill battle. In the past, mass shootings have only sparked lip service by elected officials and often faded from media coverage within a few days. The consistent inaction by elected officials makes it easy to throw up one’s hands in despair and believe nothing will ever change.

Luckily, young people haven’t bought into this hopelessness. They are far more optimistic about the future than adults. Having come up in an age of Black Lives Matter and Me Too, they have seen that collective actions can force a national dialogue and foster change which once seemed impossible. They have mastered the tools of social media and organized a national high school strike, something that hasn’t occurred since the late 1960s with anti-Vietnam war activities.

By demanding human rights, high school students now have an upper hand in the gun control debate. After all, human rights are more difficult to criticize or condemn than student rights. The question of whether a student has freedom of speech in the schoolhouse remains a contested idea. Conservative judicial officials, education and legal scholars have all blamed student rights for eroding the moral authority of school officials. A person’s right to live, on the other hand, is a basic universal principle.

Unlike elected officials, students have demanded immediate action to secure their human rights. The nationwide student walkout was a symbolic message that rejected politicians’ call to delay having a dialogue about guns in order to allow families to grieve. They have objected to unsupportive claims that school shootings happen because of video games, music, and the alleged absence of God in schools. Most importantly, they objected to the notion that there’s nothing society can do about mass shootings, as if these incidents are forces of nature rather than, too often, a result of policies that people have written (or failed to write).

Today's walkouts could be the beginning of something bigger as students harness the power of collective action to foster political and social change. It might also expand the concept of what constitutes student rights. The young have long been that catalyst for change, and the Never Again movement is a continuation of that tradition.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments