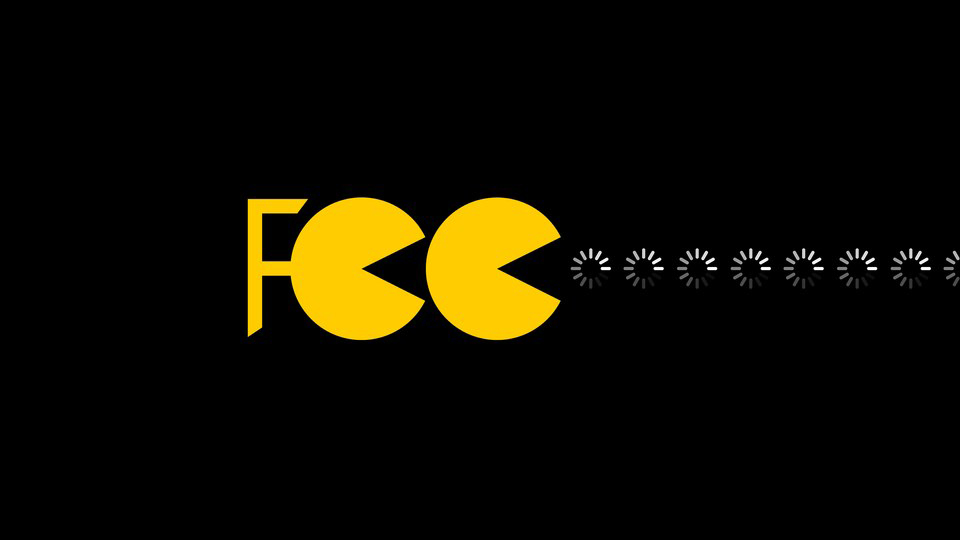

The Federal Communications Commission voted a year ago to end net neutrality – the policy that prohibited Internet service providers from discriminating against some customers in favor of others by offering better service for higher rates. The FCC calls the new rules, which partially supplanted the Obama administration’s 2015 Open Internet Order, the Restoring Internet Freedom Order. It took effect in June.

That sounds final, but the fight for net neutrality isn’t over. California passed a law this fall that guarantees net neutrality in the state (but has suspended enforcement until resolution of a legal challenge). As of early this year lawmakers in 29 other states were trying or had triedto pass similar legislation.

Whether or not these state efforts succeed, consumers should be wary about any legislative or regulatory action whose name contains the word “freedom.” The question is always freedom from what and for whom. In the corporate bubble where the Trump FCC lives – headed by a former Verizon lawyer – it generally means freedom for the powerful to put the weak at risk. As usual with “market-friendly” policy initiatives, there’s a sleight-of-hand here that makes it sound as if what’s good for elites is good for Joe the plumber.

Net neutrality’s opponents generally pull from a grab bag of cynical arguments always close at hand when corporate elites try to bend public policy toward their private advantage. That opposition seems odd given that conservatives overwhelmingly favored net neutrality not so long ago, and that the Republican-led Senate actually voted in May to restore neutrality.

Maybe Vladimir Putin explains the groundswell of pro-repeal sentiment: FCC Chairman Ajit Pai admitted recently that the agency received millions of pro-repeal comments from fake Russian e-mail addresses during the public comment period. Authentic comments were virtually unanimous in supporting neutrality.

Whatever the case, the corporate rush to colonize the Internet tramples on several arguments regularly invoked by market fundamentalists. One has to do with the government picking winners, supposedly a fatal obsession of nanny-state meddlers. But who is picking winners under a policy that gives a clear advantage to the largest players? And why shouldn’t anyone expect those players to grow ever more powerful as they consolidate and use their market power more or less as one would expect?

Another “Internet freedom” argument: Without a fast lane for some players, expansion of bandwidth will remain hampered by underinvestment. Providers must adjust pricing to capture the higher-value customers who will ultimately capitalize much-needed expansion.

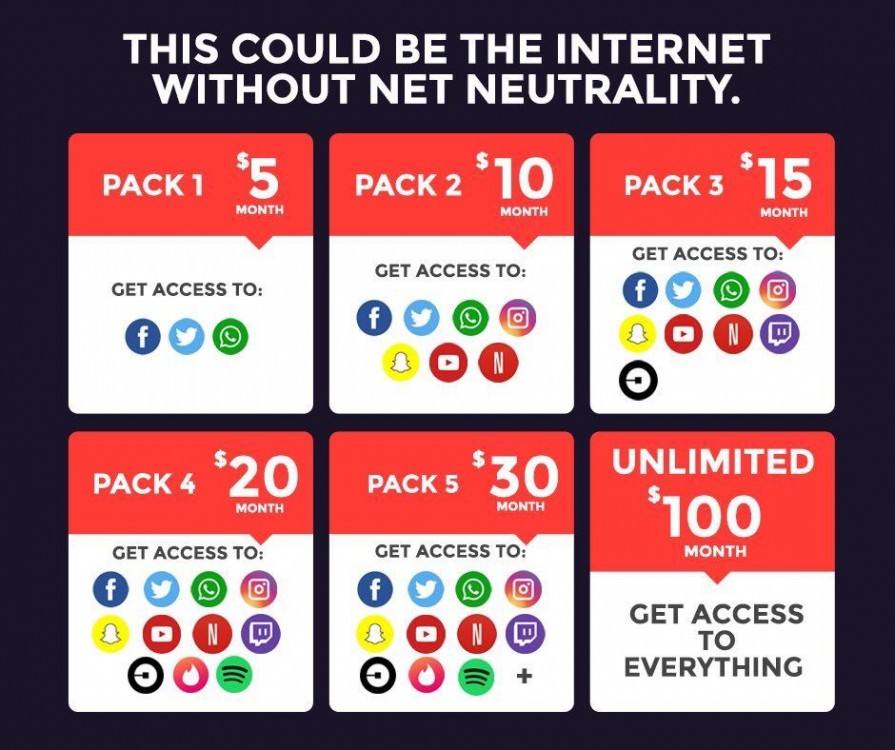

Perhaps, but there’s an equity issue that tends to get overlooked when market purists talk about “efficiency,” which is a much more complex idea than they let on. Unfettered markets tend to distribute goods and services unevenly, if only because some consumers have more purchasing power than others. You have to be agnostic about real-world outcomes not to care if some customers have superb access and others have little or none, or if struggling startups find it impossible to compete against well-funded giants who can afford the fast lane.

Free markets don’t promise equitable outcomes, and yet sometimes equity is critical. That’s one reason why some services – like the Internet until June—are treated as utilities.

You see the disequalizing effects of markets clearly in health care, to take an acute example, where “efficient” (i.e. unregulated) for-profit insurers guarantee inequitable outcomes by denying insurance to folks who aren’t profitable to cover. Obamacare, Medicare and other government programs mitigate this tendency, but the logic of market is clear: In a for-profit insurer’s perfectly efficient world, no one who has insurance would need it and no one who needs it would have it. The resulting maldistribution of healthcare would be the market outcome. How is it obvious that the faults of a regulated, “inefficient” insurance market are worse?

Internet access is arguably less crucial than healthcare access, but not by much, especially on the Internet of healthcare monitoring devices. Access matters, and unequal access can have onerous consequences for those who can’t afford the fast lane.

There is another principle here that should annoy anyone with a sense of fairness. The people who oppose net neutrality seem to regard the Internet as their personal property, and speak of government authority over it as an abomination. In their more fevered ideological moments, they assert that the government had nothing to do with the Internet’s creation (full disclosure: The author is a former colleague of mine).

But anyone one who knows something about the Internet and has no ideological axe to grind will tell you that’s simply not true. The Internet is nothing if not a product of government-funded research, developed initially under Pentagon auspices. Now the private sector comes along and treats it like a personal fief that government – aka, all the rest of us – should keep its inefficient hands off of.

Net-neutrality opponents argue that strict adherence to the principle would prohibit, for instance, carving out fast lanes for medical-device purposes or proscribe establishing free access for poor populations. Maybe, though reasonable people understand that pragmatism demands exceptions to ideological rules.

What should concern people is what tends to happen in unregulated markets. Whether or not marketizing the provision of a good or service helps consumers depends partly on input constraints. The airline industry, for example, can’t just order up a limitless increase in airports, airspace or even seats, which is why deregulation of the industry has produced such dismal results. If carriers are to compete on price, something will have to give. That something has been quality, as anyone who has flown in the past 40 years knows from experience.

It may be that the only constraint on future bandwidth is human ingenuity, which has a way of defying expectations (how many predicted the Internet 30 years ago?), and that 20 years from now the net-neutrality dispute will be a quaint relic of the technological past, like Betamax versus VHS.

In the meantime, be on guard. Trump policy makers don’t seem to care much about popular support for net neutrality, and we don’t have to speculate about how powerful Internet players behave when unconstrained. They have a track record, and it is not encouraging.

Chris Gay is a veteran of financial journalism who writes from New York City. Follow him @cgayNYC.