At 6:11 p.m. on September 6, 2010, San Bruno, Calif. 911 received an urgent call. A gas station had just exploded and a fire with flames reaching 300 feet was raging through the neighborhood. The explosion was so large that residents suspected an airplane crash. But the real culprit was found underground: a ruptured pipeline spewing natural gas caused a blast that left behind a 72 foot long crater, killed eight people, and injured more than fifty.

Over 2,000 miles away in Michigan, workers were still cleaning up another pipeline accident, which spilled 840,000 gallons of crude oil into the Kalamazoo River in 2010. Estimated to cost $800 million, the accident is the most expensive pipeline spill in U.S. history.

Over the last few years a series of incidents have brought pipeline safety to national – and presidential – attention. As Obama begins his second term he will likely make a key decision on the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, a proposed pipeline extension to transport crude from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.

The administration first delayed the permit for the pipeline on environmental grounds, but has left the door open to future proposals for Keystone’s northern route. Construction on the southern route is already underway, sparking fierce opposition from some landowners and environmentalists.

The problem, protesters say, is that any route will pose hazards to the public. While pipeline operator TransCanada has declared that Keystone will be the safest pipeline ever built in North America, critics are skeptical.

The problem, protesters say, is that any route will pose hazards to the public. While pipeline operator TransCanada has declared that Keystone will be the safest pipeline ever built in North America, critics are skeptical.

“It's inevitable that as pipelines age, as they are exposed to the elements, eventually they are going to spill,” said Tony Iallonardo of the National Wildlife Federation. “They’re ticking time bombs."

Critics of the Keystone proposal point to the hundreds of pipeline accidents that occur every year. They charge that system wide, antiquated pipes, minimal oversight and inadequate precautions put the public and the environment at increasing risk. Pipeline operators point to billions of dollars spent on new technologies and a gradual improvement over the last two decades as proof of their commitment to safety.

Pipelines are generally regarded as a safe way to transport fuel, a far better alternative to tanker trucks or freight trains. The risks inherent in transporting fuel through pipelines are analogous to the risks inherent in traveling by airplane. Airplanes are safer than cars, which kill about 70 times as many people a year (highway accidents killed about 33,000 people in 2010, while aviation accidents killed 472). But when an airplane crashes, it is much more deadly than any single car accident, demands much more attention, and initiates large investigations to determine precisely what went wrong.

The same holds true for pipelines. Based on fatality statistics from 2005 through 2009, oil pipelines are roughly 70 times as safe as trucks, which killed four times as many people during those years, despite transporting only a tiny fraction of fuel shipments. But when a pipeline does fail, the consequences can be catastrophic (though typically less so than airplane accidents), with the very deadliest accidents garnering media attention and sometimes leading to a federal investigation.

While both air travel and pipelines are safer than their road alternatives, the analogy only extends so far. Airplanes are replaced routinely and older equipment is monitored regularly for airworthiness and replaced when it reaches its safety limits. Pipelines, on the other hand, can stay underground, carrying highly pressurized gas and oil for decades – even up to a century and beyond. And while airplanes have strict and uniform regulations and safety protocols put forth by the Federal Aviation Administration, such a uniform set of standards does not exist for pipelines.

Critics maintain that while they’re relatively safe, pipelines should be safer. In many cases, critics argue, pipeline accidents could have been prevented with proper regulation from the government and increased safety measures by the industry. The 2.5 million miles of America’s pipelines suffer hundreds of leaks and ruptures every year, costing lives and money. As existing lines grow older, critics warn that the risk of accidents on those lines will only increase.

While states with the most pipeline mileage – like Texas, California, and Louisiana – also have the most incidents, breaks occur throughout the far-flung network of pipelines. Winding under city streets and countryside, these lines stay invisible most of the time. Until they fail.

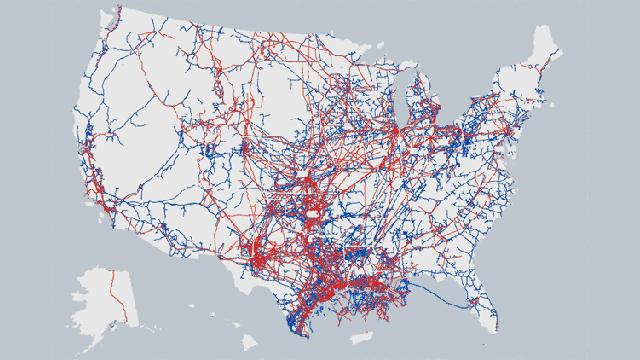

Since 1986, pipeline accidents have killed more than 500 people, injured over 4,000, and cost nearly seven billion dollars in property damages. Using government data, ProPublica has mapped thousands of these incidents in a new interactive news application, which provides detailed information about the cause and costs of reported incidents going back nearly three decades.

Pipelines break for many reasons – from the slow deterioration of corrosion to equipment or weld failures to construction workers hitting pipes with their excavation equipment. Unforeseen natural disasters also lead to dozens of incidents a year. This year Hurricane Sandy wreaked havoc on the natural gas pipelines on New Jersey’s barrier islands. From Bay Head to Long Beach Island, falling trees, dislodged homes and flooding caused more than 1,600 pipeline leaks. All leaks have been brought under control and no one was harmed, according to a New Jersey Natural Gas spokeswoman. But the company was forced to shut down service to the region, leaving 28,000 people without gas, and it may be months before they get it back.

One of the biggest problems contributing to leaks and ruptures is pretty simple: pipelines are getting older. More than half of the nation's pipelines are at least 50 years old. Last year in Allentown Pa., a natural gas pipeline exploded underneath a city street, killing five people who lived in the houses above and igniting a fire that damaged 50 buildings. The pipeline – made of cast iron – had been installed in 1928.

Not all old pipelines are doomed to fail, but time is a big contributor to corrosion, a leading cause of pipeline failure. Corrosion has caused between 15 and 20 percent of all reported “significant incidents,” which is bureaucratic parlance for an incident that resulted in a death, injury or extensive property damage. That’s over 1,400 incidents since 1986.

Corrosion is also cited as a chief concern of opponents of the Keystone XL extension. The new pipeline would transport a type of crude called diluted bitumen, or “dilbit.” Keystone’s critics make the case that the chemical makeup of this heavier type of oil is much more corrosive than conventional oil, and over time could weaken the pipeline.

Operator TransCanada says that the Keystone XL pipeline will transport crude similar to what’s been piped into the U.S. for more than a decade, and that the new section of pipeline will be built and tested to meet all federal safety requirements. And in fact, none of the 14 spills that happened in the existing Keystone pipeline since 2010 were caused by corrosion, according to an investigation by the State Department.

The specific effects of dilbit on pipelines – and whether the heavy crude would actually lead to more accidents – is not definitively understood by scientists. The National Academies of Science is currently in the middle of study on dilbit and pipeline corrosion, due out by next year. In the meantime, TransCanada has already begun construction of the southern portion of the line, but has no assurance it will get a permit from the Obama administration to build the northern section. (NPR has a detailed map of the existing and proposed routes.)

Little Government Regulation for Thousands of Miles

While a slew of federal and state agencies oversee some aspect of America’s pipelines, the bulk of government monitoring and enforcement falls to a small agency within the Department of Transportation called the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration – pronounced “FIM-sa” by insiders. The agency only requires that seven percent of natural gas lines and 44 percent of all hazardous liquid lines be subject to their rigorous inspection criteria and inspected regularly. The rest of the regulated pipelines are still inspected, according to a PHMSA official, but less often.

The inconsistent rules and inspection regime come in part from a historical accident. In the 60's and 70's, two laws established a federal role in pipeline safety and set national rules for new pipelines. For example, operators were required to conduct more stringent testing to see whether pipes could withstand high pressures, and had to meet new specifications for how deep underground pipelines must be installed.

But the then-new rules mostly didn’t apply to pipelines already built – such as the pipeline that exploded in San Bruno. That pipeline, which burst open along a defective seam weld, would never have passed modern high-pressure requirements according to a federal investigation. But because it was installed in 1956, it was never required to.

"No one wanted all the companies to dig up and retest their pipelines," explained Carl Weimer, executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, a public charity that promotes fuel transportation safety. So older pipes were essentially grandfathered into less testing, he said.

Later reforms in the 1990’s mandated more testing for oil pipelines, and today PHMSA requires operators to test pipelines in "high consequence" areas, which include population centers or areas near drinking water. But many old pipelines in rural areas aren’t covered by the same strict regulations.

Some types of pipelines – such as the “gathering” lines that connect wells to process facilities or larger transmission lines – lack any PHMSA regulation at all. A GAO report estimates that of the roughly 230,000 miles of gathering lines, only 24,000 are federally regulated. Because many of these lines operate at lower pressures and generally go through remote areas, says the GAO, the government collects no data on ruptures or spills, and has no enforced standards for pipeline strength, welds, or underground depth on the vast majority of these pipes.

The problem, critics argue, is that today’s gathering lines no longer match their old description. Driven in part by the rising demands of hydraulic fracturing, operators have built thousands of miles of new lines to transport gas from fracked wells. Despite the fact that these lines are often just as wide as transmission lines (some up to 2 feet in diameter) and can operate under the same high pressures, they receive little oversight.

Operators use a risk-based system to maintain their pipelines – instead of treating all pipelines equally, they focus safety efforts on the lines deemed most risky, and those that would cause the most harm if they failed. The problem is that each company use different criteria, so "it's a nightmare for regulators," Weimer said.

However, Andrew Black, the president of the Association of Oil Pipe Lines, a trade group whose members include pipeline operators, said that a one-size-fits-all approach would actually make pipelines less safe, because operators (not to mention pipelines) differ so widely.

"Different operators use different pipe components, using different construction techniques, carrying different materials over different terrains," he said. Allowing operators to develop their own strategies for each pipeline is critical to properly maintaining its safety, he contended.

Limited Resources Leave Inspections to Industry

Critics say that PHMSA lacks the resources to adequately monitor the millions of miles of pipelines over which it does have authority. The agency has funding for only 137 inspectors, and often employs even less than that (in 2010 the agency had 110 inspectors on staff). A Congressional Research Service report found a “long-term pattern of understaffing” in the agency’s pipeline safety program. According to the report, between 2001 and 2009 the agency reported a staffing shortfall of an average of 24 employees a year.

A New York Times investigation last year found that the agency is chronically short of inspectors because it just doesn’t have enough money to hire more, possibly due to competition from the pipeline companies themselves, who often hire away PHMSA inspectors for their corporate safety programs, according to the CRS.

Given the limitations of government money and personnel, it is often the industry that inspects its own pipelines. Although federal and state inspectors review paperwork and conduct audits, most on-site pipeline inspections are done by inspectors on the company’s dime.

The industry’s relationship with PHMSA may go further than inspections, critics say. The agency has adopted, at least in part, dozens of safety standards written by the oil and natural gas industry.

"This isn't like the fox guarding the hen house," said Weimer. "It's like the fox designing the hen house."

Operators point out that defining their own standards allows the inspection system to tap into real-world expertise. Adopted standards go through a rulemaking process that gives stakeholders and the public a chance to comment and suggest changes, according to the agency.

Questions have also been raised about the ties between agency officials and the companies they regulate. Before joining the agency in 2009, PHMSA administrator Cynthia Quarterman worked as a legal counsel for Enbridge Energy, the operator involved in the Kalamazoo River accident. But under her leadership, the agency has also brought a record number of enforcement cases against operators, and imposed the highest civil penalty in the agency’s history on the company she once represented.

Proposed Solutions Spark Debate

How to adequately maintain the diversity of pipelines has proved to be a divisive issue – critics arguing for more automatic tests and safety measures and companies pointing to the high cost of such additions.

One such measure is the widespread installation of automatic or remote-controlled shutoff valves, which can quickly stop the flow of gas or oil in an emergency. These valves could help avoid a situation like that after the Kalamazoo River spill, which took operators 17 hours from the initial rupture to find and manually shut off. Operators use these valves already on most new pipelines, but argue that replacing all valves would not be cost-effective and false alarms would unnecessarily shut down fuel supplies. The CRS estimates that even if automatic valves were only required on pipelines in highly populated areas, replacing manual valves with automatic ones could cost the industry hundreds of millions of dollars.

Other measures focus on preventing leaks and ruptures in the first place. The industry already uses robotic devices called "smart pigs" to crawl through a pipeline, clearing debris and taking measurements to detect any problems. But not all pipelines can accommodate smart pigs, and operators don’t routinely run the devices through every line.

Just last month, a smart pig detected a “small anomaly” in the existing Keystone pipeline, prompting TransCanada to shut down the entire line. Environmentalists pointed out that this is not the first time TransCananda has called for a shut down, and won’t be the last.

“The reason TransCanada needs to keep shutting down Keystone,” the director of the National Wildlife Federation contended in a statement, “is because pipelines are inherently dangerous.”

Last January, Obama signed a bill that commissioned several new studies to evaluate some of these proposed safety measures, although his decision on extending the Keystone pipeline may come long before those studies are completed.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments