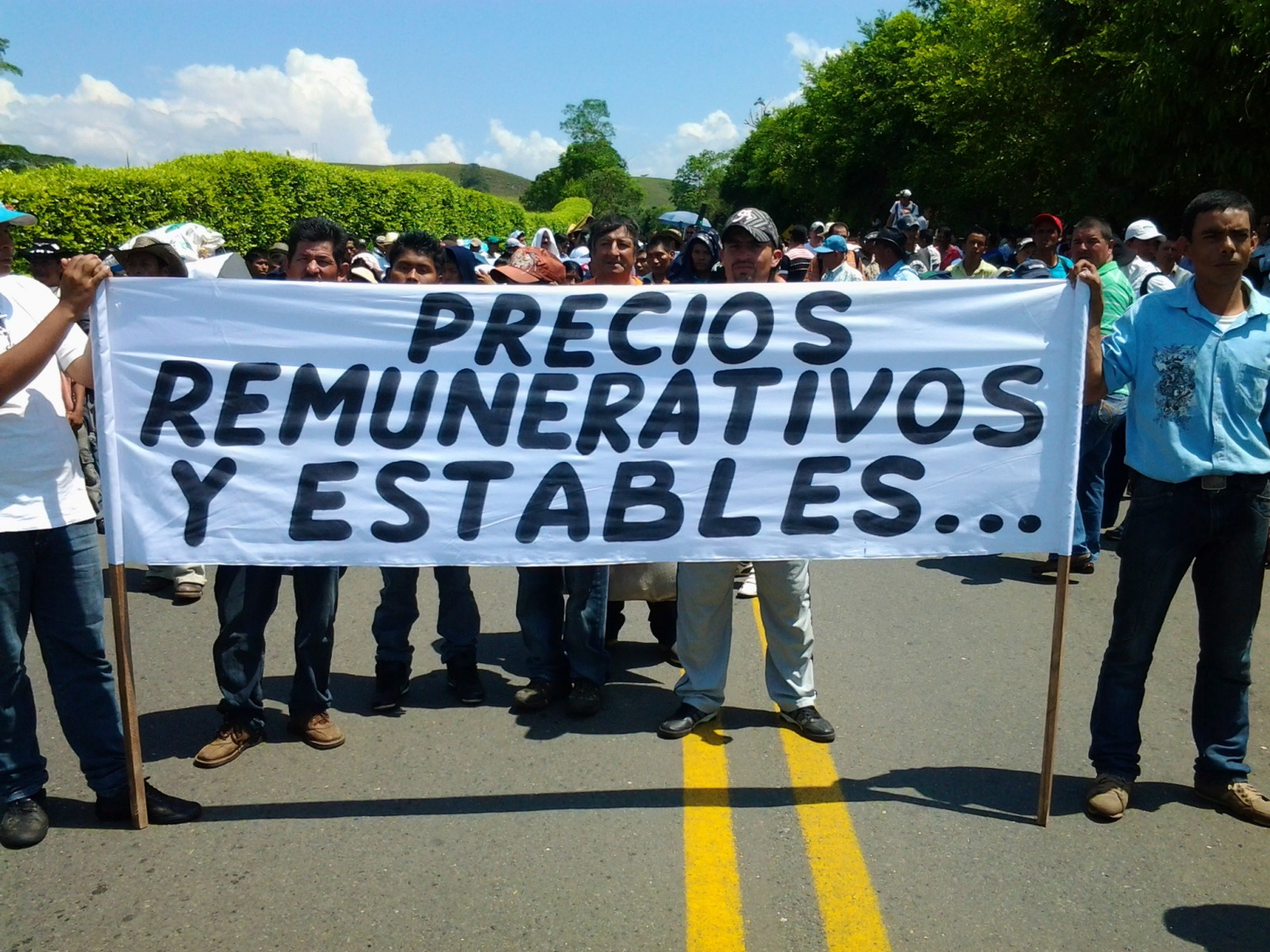

Agrarian workers, truckers, miners, and coffee growers in Colombia have staged a national strike for more than a week now to protest government indifference and economic hardships brought about by free trade agreements and lack of regulation.

The strikers have called for marches, manned dozens of roadblocks on some of the country’s key highways, and fought riot police in an escalating conflict that is costing the nation more than one billion dollars.

The government has responded with calls for composure and accusations of outside manipulation. Since the strike began on Aug 19, President Juan Manuel Santos has tried to minimize the strikers’ actions, giving statements that have only served to taunt protesters and bring together union leaders.

“The so-called agrarian strike does not exist,” Santos said on Sunday. Acts of violence, the president said, were caused by guerrilla infiltrators – an often-used government claim -- who wanted to destabilize the country and hamper dialogues with troubled agrarian sectors. “It’s just 10 or 15 people. The situation is under control and problems are being resolved,” Santos added.

For the general public, the president’s account is confounding at best. The situation is far from being under control. Basic food prices have doubled in some towns and cities, and few if any transport trucks or commercial vehicles are running through some of the country’s busiest states. Thousands of tons of produce are rotting or are being thrown away in more than five states since truckers are afraid to drive around the country to deliver their orders.

Five people have been killed and hundreds more have been injured in the numerous skirmishes that plague the countryside, according to police reports. Students in public universities have attacked authorities with rocks and homemade bombs. Protesters have burned cars and trucks, and an unknown group in Boyacá, a historically peaceful agrarian state located a few hours north of the nation’s capital, reportedly placed a cable line across a road late in the afternoon to kill an unsuspecting motorist that drove by. Red Cross medical missions have been detained at roadblocks, and there have been disturbances in more than half of the nation’s states.

“We’ve witnessed… a growth in the level of aggressiveness and violence,” General Rodolfo Palomino, the National Police’s director of citizen security, said last Friday after capturing four men carrying heavy explosives in Huila, a state in the country’s southwestern region. “The police has captured 175 people,” he added later.

Why are people protesting?

All in all, there are four major groups leading the strike: potato growers, coffee planters, and other farmers from the country’s interior; milk and dairy producers; truckers; and small-scale miners. Each group has its own grievances, most of which date back several months.

Potato growers and other agrarian workers argue that free trade agreements with the United States and the European Union are destroying Colombian farming.

According to union leaders, the lack of government subsidies coupled with the excessive price of fertilizers make it impossible to compete with imported foreign products. Colombia uses more fertilizers than any other country in the Western Hemisphere, and local monopolies make the price of these chemicals between 25 and 45 percent higher than in other nations.

On top of that, most of the profits of many agrarian products tend to end up in the hands of intermediaries. As Semana magazine has reported, growers sell a parcel of potatoes for around $7. That same parcel is then sold to as many as eight intermediaries until it ends being bought by restaurants in Bogotá or other main cities for nearly $17 to $23.

Milk and dairy producers face similar problems. Milk imports have more than tripled since 2006, according to official figures. Producers now sell a liter of milk for approximately 21 cents, an amount that makes the business unfeasible, according to trade associations.

For truckers, complaints have to do with freight and gasoline prices. The country’s two biggest unions had already gone on strike last March over gasoline prices, which have increased three times as much as the inflation rate over the past three years. Truckers have asked for subsidies and for further price reductions.

The problem with small-scale miners can be traced back a number of years and it is closely associated with the criminal groups that Colombian authorities fight against on a daily basis.

Colombia has always had a problem with illegal mining – only 37 percent of mining activities in the country are certified -- but it was only until three or four years ago that groups like the FARC guerrrillas and Los Rastrojos, a paramilitary squad, started heavily investing their resources on mining Since then, authorities have cracked down on illegal mining, seizing and destroying machinery from both armed groups and small-scale miners. The strike aims to stop this sort of law enforcement strategy.

What is the Government Doing to End the Strike?

Despite Santos stating that Colombia will not negotiate with the farmers during the strike, the government is now negotiating with union leaders to end it. As of Monday afternoon, though, negotiators had not reached an agreement with union leaders, and Santos was forced to travel to Tunja, Boyacá’s capital, to try to resolve the issue.

Thus far, the government has acceded to approximately $1.5 billion in credit lines, subsidies, and tax breaks. But that figure doesn’t cut it, according to union leaders.

“We don’t think it’s viable or sustainable to achieve full development of the sector’s policy with the current budget allocation,” Rafael Mejía López, President of the Sociedad de Agricultores de Colombia, told El Colombiano.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments