For those who hold a critical lens to the American economy, one overwhelming fact is unavoidable: The four largest U.S. banks — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup and Wells Fargo — are immensely big. As a matter of fact, these four banks — at $7.8 trillion in combined assets — constitute half of the nation’s entire economy and hold more than half of the nation’s fiscal deposits.

According to conventional wisdom, the collapse of any one of these banks would not only drag the nation into recession, but create a depression so grave that the nation would be permanently compromised.

In 2010, former Rep. Barney Frank (D-N.Y.) and former Sen. Chris Dodd (D-Conn.) introduced the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act — one of the most comprehensive fiscal reform packages introduced since Franklin D. Roosevelt’s banking industry reforms — as a way to mitigate this threat.

Dodd-Frank introduces new checks on the banks to ensure consumer protection and fiscal solvency, removes prosecutorial immunities that the banking industry enjoyed for decades, forces new safeguards, makes certain types of derivatives and securities trading illegal and forces the banks and other financial institutions to operate within a new framework of regulations designed to ensure ethical practices.

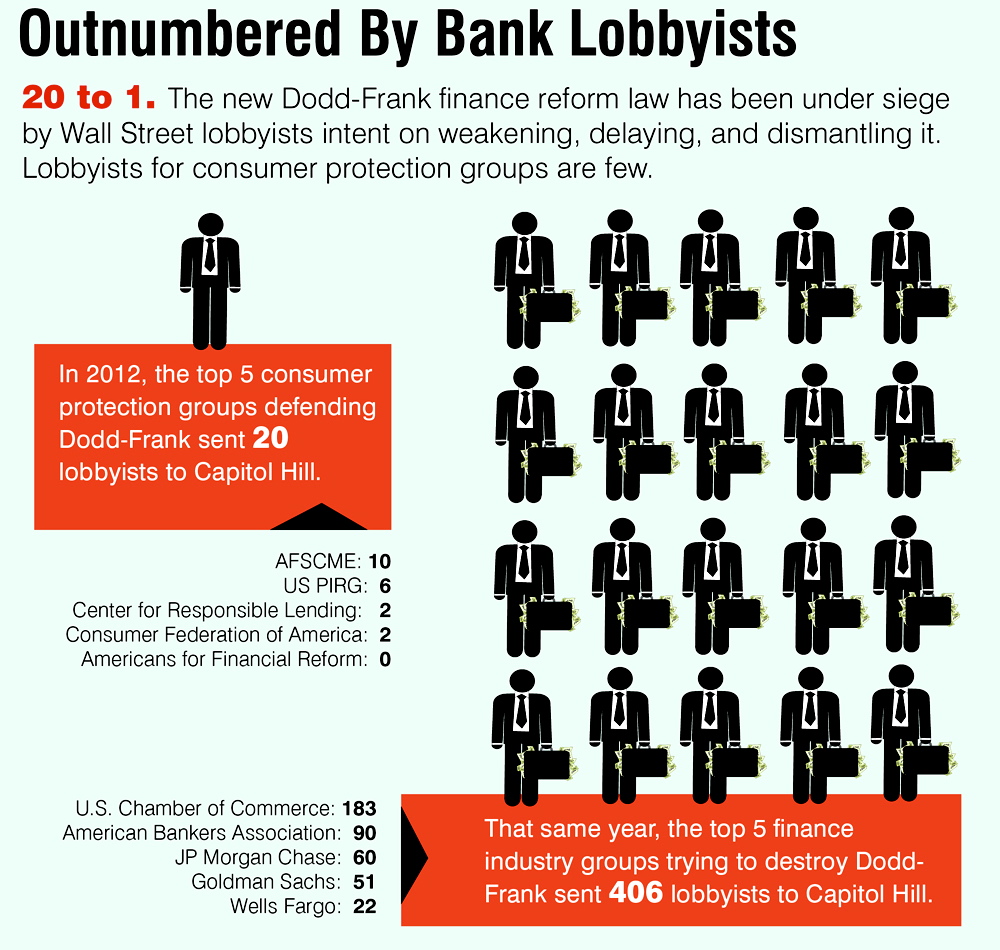

From the start, Dodd-Frank has been challenged by congressional Republicans. Advocating for the major banks, the Republicans blocked the appointment of now-Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) as the first director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) — the primary consumer fiscal advocate established under Dodd-Frank — and have blocked the confirmation of recess-appointed CFPB Director Richard Cordray.

Regulators — essential to this bill, which heavily relies on them for its implementation — seemed unwilling or unable to challenge banking executives on issues of executive pay and bonuses, repayment of rescue money from the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), accountability toward consumer protection and avoidance of risky investments.

More damningly, a culture of recovering assets instead of pursuing criminal prosecution for major financial crimes has created an atmosphere in which fines and reparations are an acceptable cost of doing business.

Different Approaches

This week, Dodd-Frank will face two tests on Capitol Hill. On one hand, a bipartisan bill introduced by Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) and David Vitter (R-La.) will force all banks with more than $500 billion in assets to create a safety cushion of equity capital equal to at least 15 percent of all assets.

The bill would also limit the practice of “risk-weighting,” or the manipulation of risk calculations to make fiscal balance sheets seem falsely safe. This will force the Big Four out of much of their auxiliary business, defusing systematic risk. This new proposal is at odds with Basel III (the Third Basel Accord), which are voluntary, global regulatory standards that call for a reserve of 6 percent of a bank’s common shares and retained earnings, and 4.5 percent of a bank’s common equity.

Conversely, a set of bills are scheduled to be reviewed Tuesday by the House Committee on Financial Services, which would seriously defang Dodd-Frank. The slew of bills would largely undo regulatory control of derivative swaps imposed by Dodd-Frank.

It should be noted that the 2008-2009 recession was triggered by defaulted mortgages-derivative swaps.

Depending on what direction Congress takes, Dodd-Frank is likely to change, and in the process, so will the certainty and safeness of the American economy.

Option A: Strengthen Dodd-Frank

In 2010, an interesting conversation took place: Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.) wrote a letter to then-Secretary of the Treasury Tim Geithner inquiring about the amount of capital a bank should be required to carry as insurance against future defaults. Ellison requested the Treasury Department’s advice on whether it would be a good idea to write a specific leverage ratio into Dodd-Frank itself.

In Geithner’s response, the secretary argued that “[placing] fixed, numerical capital requirements in statute will produce an ossified safety and soundness framework that is unable to evolve to keep pace with change and to prevent regulatory arbitrage. Fixed, numerical statutory capital requirements also could hinder the Federal Reserve and other banking agencies as they strive to make their capital requirements less pro-cyclical and explore the costs and benefits of making capital requirements affirmatively counter-cyclical.” Geithner argued that the ratio should be left to the regulators, and it was.

However, the lack of capital that the Dodd-Frank rules require and the freedom they give the banks to determine the level and quality of commitment have been raising red flags. The Brown-Vitter legislation was designed to take on the issue of inadequate capital ratios.

To explain why this is important, let’s look at the issue of “leverage.”

“Leverage” is the ratio of what is borrowed to what is available at hand. So, a car purchased at 5 percent down has a leverage of 20 to 1. So for every one dollar physically available to buy the car, $19 were borrowed. For a bank, leverage gives banks more money to invest and more money from which to draw a return. This also makes the borrower fragile. In the case of the car, should the borrower lose up to or less than the 5 percent of the car’s cost that were physical assets, the borrower can still repay his loan at the terms negotiated. However, should the borrower lose more than what he originally had — the 5 percent, in this case — the loan is no longer repayable, as the borrower has no money to repay it other than borrowed funds, which — obviously — are not available.

The way to handle this is to set money aside that is untouchable. Should a person lose their cash-on-hand, the loan will still be viable because of the money set aside. This is known as a capital reserve. Many banks adjust their capital reserve based on the leverage they are actively engaged in. As a smaller reserve releases more funds that can be leveraged, many banks “conservatively” estimate their assumed risk, or “risk-weight” their assets. This becomes an issue when, as seen in 2008, the resulting reserve is much too small to pay back the cash-on-hand for the risk assumed.

This is where Brown-Vitter comes in. Brown-Vitter artificially forces a larger-than-necessary reserve — based on a bank’s assets, not its debt portfolio. Doing so renders a bank “unfailable,” because — unless a bank takes reckless risks — it will always have cash on hand.

Under Basel III, capital reserves are capped at 8 percent of all “risk-weighted” assets. Brown-Vitter would set a baseline of 10 percent of a bank’s common equity, with extra capital — up to 15 percent of all assets — added to capital reserves of firms that hold more than $400 billion. On top of this, all assets must be considered, not just “risk-weighted” ones.

The administration is not a fan of Brown-Vitter. It prefers that banking regulators be the ones that handle the enforcement of capital reserves. Since anyone who can handle a situation can always choose not to, legislating ratios may be, at least, the least-bad option.

Option B: Let the Banks “Regulate” Themselves

This, of course, is not how most of the Republican caucus sees the issue. For them, the 2008-2009 mortgage crisis was a fluke and therefore no reason to take away the banks’ ability to self-regulate. In this vein, the Committee on Financial Services are currently considering legislation that will wipe clear Dodd-Frank’s control on derivatives swaps.

A “derivative” is a contract. Designed to dictate the terms of payment between two parties, it “derives” its value from the commodity being traded. So, a mortgage swap derivative is the payment arrangement for the swapping of mortgage bearer certificates.

As the derivative itself is a financial instrument representing the risk of a transaction, it can represent a lucrative opportunity. For example, a corporation takes on a loan with an interest rate that changes every six months. To protect itself, the corporation enters a form of derivative known as a forward rate agreement (FRA), in which the interest rate is set. If the actual rate is higher than the FRA rate, the holder of the FRA pays the difference. However, if the actual rate is lower than the FRA rate, the corporation pays the FRA holder the difference.

Such assets are extremely uncertain and are prone to speculation. It was this speculation on the derivatives on defaulted mortgage swaps between banks that inflated the banks’ risk portfolio beyond their cash-in-hand and led to the 2008-2009 mortgage crisis.

The bills before the Financial Services Committee would allow derivatives to be traded by American firms outside of the United States, would allow fiscal corporations to engage in derivatives and would allow non-FDIC-insured derivatives to be deposited in the insured bank.

This is a nightmare scenario, because derivatives have seniority in bankruptcies. If this bill package is passed and if a bank that has deposited derivatives fails, the capital reserve must be used to pay the derivatives first, and any hedge funds that have traded derivatives with the bank, as derivatives are exempt from the automatic stay. This may leave insignificant reserves to pay off the consumer and business deposits. As the deposits are FDIC-insured, that will force the Federal Reserve to issue a loan to cover the deposits.

So, in effect, these bills would create an automatic bailout system.

These bills are likely to pass the Republican-controlled committee, though if they pass the House, they are almost assured a quick death on the Senate floor. However, many Democrats have come forward in support of the bills, including Reps. Jim Himes (D-Conn.), David Scott (D-Ga.) and Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.). All of these politicians have deep roots in Wall Street.

In recent years, the Big Four have begun to play with derivatives regulation. In light of debt rating downgrades, Bank of America moved its Merrill Lynch derivatives to its retail subsidiary. As Bank of America’s security market is not FDIC-insured, but its retail operation is, this passed the risk to the taxpayers.

As Jon Weil of Bloomberg explained:

“The market harbors serious doubts about whether Bank of America has enough capital … Dodd-Frank lets the FDIC borrow money from the Treasury to finance a seized company’s operations for as long as five years. While the law says the FDIC is supposed to tap the banking industry to pay for any eventual losses, it’s hard to imagine the agency could ever charge enough to cover the costs from a failure at a company with $2.2 trillion of assets.”

In the next few months, Dodd-Frank will change. The question remains if the change will serve Wall Street or the people.

Originally published by MintPress News.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments