In what has become one of the most controversial “terror” cases in modern U.S. history, the Cuban Five gained renewed support in San Francisco recently when hundreds of protesters called on the government to release the group that has been in jail on murky charges since 1998.

Highlighting the inconsistencies involved in trying American terror-related cases, activists argued that the 16-year-long incarceration of the Cuban Five is an injustice that needs urgent rectification – in tandem with, though not directly related to, the closure of Guantanamo Prison in Cuba – if the U.S. is to regain a moral foothold internationally.

“Now that evidence has been brought forward showing that the U.S. government was attempting to scapegoat these people instead of looking at the evidence,” said one San Francisco protester who asked not to be named, “I want to support justice and a country’s right to defend itself from attack.”

Many Americans are still unfamiliar with the case of the Cuban Five, whom the Cuban government admitted, three years after their arrest, were intelligence agents monitoring Cuban exiles in Miami – and were reportedly working to stop terror attacks planned for Cuba. The U.S. long ago charged them with espionage and sentenced them to prison.

According to official statements from Havana, the men were helping to stop terrorist activity against the Cuban government, which saw a number of bombings in the capital in the 1990s – events that prompted the government of Fidel Castro to step up its monitoring of Cubans living in Miami.

On Sept. 12, the 16th anniversary of their arrest, social justice activists and scores of other supporters of the Cuban Five gathered for a poetry reading by renowned Cuban poet Nancy Morejón, who energized the crowd with her words defending those she said have been wrongfully imprisoned for attempting to stop violence from occurring in her country.

Morejón told the crowd that “it was important to look at these people as human beings” who deserve “the ability to tell their story without the prejudices” advanced by the U.S. government over the past decade and a half.

For her and others attending the San Francisco rally on the anniversary of the group's arrest, the Cuban Five represent the hypocrisy of the American government's position addressing terror-related cases.

“Whether you believe that Cuba made the right decision to have agents tracking people in Miami is irrelevant,” said Rick Hernandez, a 39-year-old Oakland resident. “It seems okay for the U.S. to do whatever it wants in whatever country, including killing civilians – but when another country wants to track potential militants, that’s not allowed. Seems a little hypocritical to me.”

History of a Controversial Case

In many ways, the story of the Cuban Five started decades before their arrest, when Cuban citizens began to take refuge in southern Florida after the takeover of Havana by Fidel Castro and his revolutionary forces in 1959. Cuba has long maintained that in the decades since, paramilitary and anti-Cuban groups established in Miami with the backing of the FBI and CIA carried out attacks on Cuban soil against Castro and his government.

According to statistics, the unofficial conflict has left more than 2,000 people dead and another several thousand wounded as Havana fought various exile groups including Comandos F-4 and Brothers to the Rescue, the Cuban-American National Foundation’s armed wing. Cuba claims many individuals in these and other organizations have acted with the full support and backing of American officials.

After a string of attacks in the 1990s, Cuban established “La Red Avispa," or Wasp Network, aimed at monitoring and infiltrating the alleged paramilitary groups that had carried out attacks, including Comandos F-4.

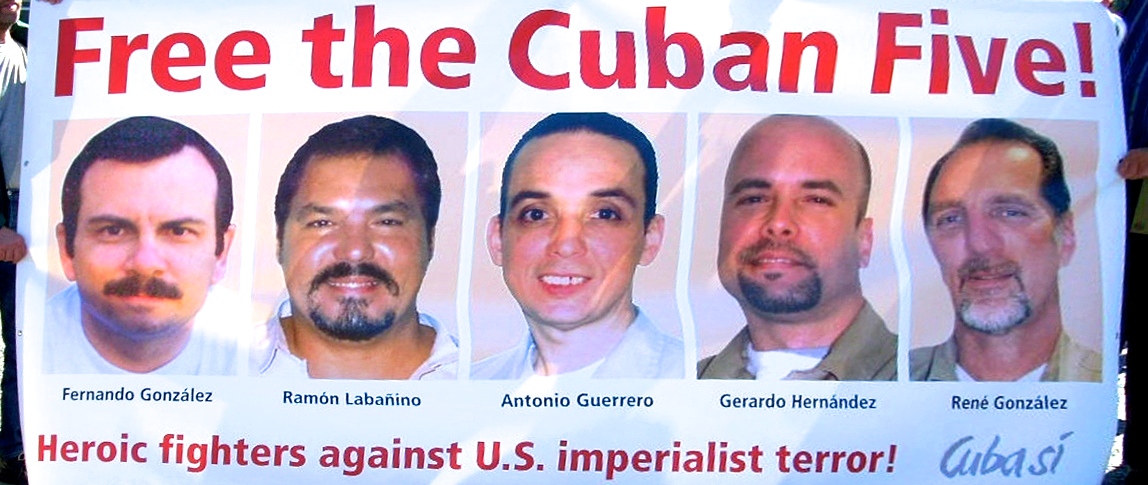

The five who were arrested by the FBI on Sept. 12, 1998, include Gerardo Hernández, Antonio Guerrero, Ramón Labañino, Fernando González and René González. The men were charged and convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage and murder.

They were also charged with acting as agents of a foreign government and other undeclared “illegal” activities in the United States.

Guerrero has maintained the men were simply monitoring the paramilitary groups and reporting back to Havana in an effort to avoid further violence in the country. The court in Miami, however, disagreed and sentenced them all to prison.

The Five appealed their convictions, citing a lack of fairness in the trial. And in 2005, a U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit in Atlanta overturned their convictions. In its ruling, the court argued that widespread anti-Castro sentiment among Cubans in Miami did not allow for a fair trial to occur. However, the full court reversed the attempt for a new trial and reinstated the original convictions.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case in 2009.

Two of the Five have since been released. René González was let out of jail on Oct. 7, 2011, after serving 13 years, but was not allowed to leave the country until he completed a three-year probation period in the U.S. The U.S. let him return to Cuba in April 2013 to attend his father’s funeral, whereby a federal judge allowed him to remain in Cuba if he renounced his American citizenship.

Fernando González completed his sentence on February 27, 2014. The other three convicted men remain in jail. Labañino is expected to be freed this October, and Guerrero is scheduled to be released in September of 2017. Hernandez is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

While Cuban Five supporters and anti-Cuban activists remain split down the middle, the rise of non-Cuban activists siding with the group has grown – especially as the U.S. escalates its War on Terror through drone strikes and other activities around the globe. For many activists, the American government's crackdown on potential terrorists is similar to what Cuba attempted to do in the late 1990s.

“I just want there to be justice,” said Mark Minna, who joined the poetry reading because he said he wanted to learn "another side to the issue."

For Minna, the case has long been one of foreign spies attempting to foment violence among the Cuban exile population. But he said he now understands that even if the Five were guilty of working for a foreign government, “they didn’t pose a threat to this country and should have not received those ridiculously long sentences, because we now know the extent [that] the U.S. went” to criminalize them.

According to the Free The Five national movement, the U.S. government explicitly paid journalists to concoct stories against the Cuban Five as the trial was underway in order to get public support behind the rulings.

Now, 16 years later, “We need to come together for peace and unity,” added the poet Morejon in her comments to the audience.

Seeking Political Change Between the U.S. and Cuba

As sanctions against Cuba continue to be viewed as a counterproductive measure that harms more than helps average Cuban citizens, a growing cadre of U.S. activists – and general citizenry – is pushing to end the decades-long antagonism between Washington and Havana. If a political breakthrough were to occur, many claim, it could help free the three men who remain behind bars.

González, whom the Cuban government lauds as a national hero, told the Associated Press that one of the more positive signs he's seen is former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton's statement in her recent book recommending President Obama to end the embargo on Cuba. González argued this move would open up new ways to help those who've been jailed as a result of the countries' tension, including American citizens languishing in Cuba.

"At this moment there's a political context that makes me cautiously optimistic," said González. "There's a growing interest in changing U.S. policy toward Cuba. I would like to think that before finishing his term, President Obama would decide to improve relations with Latin America. That would involve a change with Cuba and would necessarily take place through a solution to the case of my three colleagues."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments