In the run-up to its September convention, the national AFL-CIO is calling on its affiliates and allies to hold “listening sessions.” We’re being asked to think big.

With union density at 11.3 percent and unions facing a not-so-gradual decline toward irrelevance, leaders are having “a come-to-Jesus moment.”

The “Building a Movement for Shared Prosperity” project urges unions to reach beyond officials and staff to members (including those in non-AFL-CIO unions), non-union workers, civil rights, immigrant, LGBT, and youth groups, the unemployed, and worker centers.

In fact, more delegates are expected to attend the Los Angeles convention from allied organizations than from AFL-CIO affiliates.

So far more than 6,000 people have joined the discussion in person or online. Some comments from the AFL website and from two listening sessions in Vermont:

I have been waiting for 40 years for the AFL-CIO to ask me what I think.

-

Let’s revisit the Knights of Labor and create a 21st-century version. Central labor councils once represented all working-class institutions, not just AFL-CIO unions.

-

We will have to change our structures just in order to survive as meaningful working-class institutions. Today more and more working people are considered “independent contractors” (just look at the trucking industry, where we no longer have a Master Freight Agreement—once representing 300,000 workers—now mostly so-called owner operators), work multiple part-time or temporary jobs, work for very small employers, etc. We are atomized and divided from each other.

-

The pay and benefits of union officials and staff should be reduced to that of those they represent.

-

Labor and environmental movements should work together for conversion from dirty energy to renewable energy, insuring a just transition that protects the workers; likewise conversion of military production to infrastructure jobs and jobs producing socially useful goods and services.

“A repeated theme among participants,” the AFL-CIO reports, “is advocating that the labor movement invest more in our own infrastructure and in organizing and less in the Democratic Party—and to hold elected Democrats accountable for their votes on working family issues.

“The recent experiences of the Chicago Teachers Union strike, the fight against the school closings and the Walmart campaign give the labor movement a wealth of experiences in building labor-community solidarity to mull over.”

Nevertheless, leaders who would like to see the AFL-CIO begin to “put the movement back in the labor movement” are concerned that, unless unions that currently give huge amounts to the Democratic Party agree to redirect some of that to the AFL-CIO to fund internal organizing, education, and community engagement, the federation will lack the capacity to actually begin “building a movement for shared prosperity.”

Jeff Crosby, president of the North Shore Labor Council near Boston, notes that the AFL-CIO’s Solidarity Fund was a good start. It is funded by an additional per capita from affiliated unions, imposed after the Change to Win unions left and caused a financial crisis for the federation.

But it doesn’t have the money even to fund current requests from state feds and central labor councils, which can be expected to skyrocket if every CLC is required to have a program of “community engagement,” as is contemplated.

“A big challenge will come after the convention,” Crosby said. “Will there be the political will, money, and staff to implement whatever resolutions are passed? The AFL-CIO does not have its own troops separate from the international unions.”

Local Vision Version

The Vermont AFL-CIO wants to use the opportunity this summer to engage rank-and-file members beyond the usual suspects, build relationships, and develop a vision of a relevant labor movement.

It’s proving difficult. Most of those at our first two “Town Meetings on Work with Dignity” were already active with the Vermont Workers Center, the local Jobs with Justice affiliate. We had 35 and 20 people at the two sessions.

The unions with the most members and staff there were non-AFL-CIO unions: United Electrical Workers and Vermont State Employees Association (which is trying to become an organizing union).

Frankly, we were proven wrong that we could connect with a significant number of our own members by inviting them to a listening session. Even for local leaders, focused on grievance handling and contract negotiations, discussing the big picture is challenging. One central labor council president offered that this was the result of the culture of “an unraveling business unionism.”

This is the harsh truth—although our state federation collaborates well with the Workers Center, supports the campaigns of Vermont Migrant Justice, has vigorously supported Vermont’s move toward universal health care, is affiliated to the Labor Campaign for Single Payer and U.S. Labor Against the War, and often supports Vermont’s third party, the Progressive Party (while generally supporting Democrats).

There is no escaping the reality that most of our members feel additional participation in union activity would have little relevance to their lives. The routines of bargaining contracts, occasional grievance handling, lobbying the legislature—all done by a handful of staff and officers—have left members disengaged.

Politics the Answer?

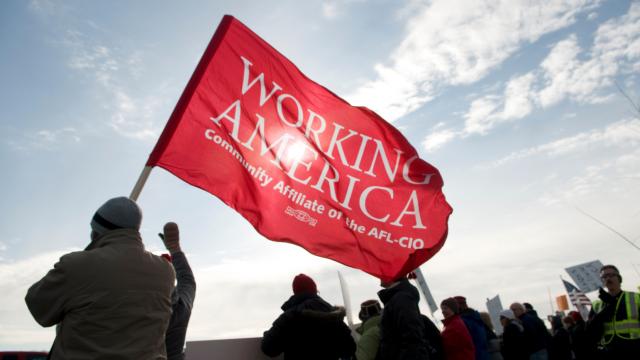

In the hostile environment for bargaining and organizing, unions have looked to politics to rescue us from irrelevance. There is a real danger that the AFL-CIO convention will approve a policy that continues in that direction—seeing the federation’s community arm Working America, and even unions themselves, primarily as political campaign and pressure vehicles.

On the contrary, we need more of a focus on workplace activity, because that is precisely where members can develop their sense of power and self-confidence.

Dissident United Auto Workers regional director and labor strategist Jerry Tucker located the roots of labor’s decline in “labor’s culture—its actual activity and what it represents to workers.

“Organized labor doesn’t represent a movement at this point that workers can attach themselves to,” Tucker said, “where they feel a certain sense of upsurge or upward momentum.”

That sense of upsurge is what we have to create. The transformations we need are on a greater scale than those of the 1930s that took labor from craft unionism to industrial unionism.

Another Way

The Chicago Teachers Union is an inspiring example. New officers cut their own pay, prioritized internal organizing, and started rebuilding their union on democratic, “social-movement unionism” principles, meaning they take on their allies’ issues—even if it means fighting employers and the government.

Unions that focus resources into internal organizing can get results, particularly if we organize around the issues members confront in the workplace.

Closer to home in Vermont, new organizing by health care and homecare workers and early childhood educators is breathing new life into our labor movement.

Not coincidentally, all the major advances in organizing Vermont unions in recent years have been accomplished in collaboration with allies, particularly the Vermont Workers Center. We need this kind of community engagement if we are to build a massive movement that fights for all working people.

There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical about where the listening sessions may go on the national level. But on the local level there are still five weeks left before the AFL-CIO convention to provoke a discussion.

Traven Leyshon is secretary-treasurer of the Vermont State Labor Council, AFL-CIO.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments