Solar is happening right now, but maybe you didn’t hear? Somehow in all the hubbub of the GOP (Good Ol’ Petroleum) takedown — and amid debate about how much Keystone XL focus is too much Keystone XL focus — news about solar power infrastructure in the U.S. hasn’t reached everyone’s front page.

So here’s a cheerful update from the American Southwest: two enormous solar thermal power plants are coming online, step-by-step, right as you're reading this.

In California, BrightSource Energy’s Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System is slated to be the largest solar power plant in the world. At a cost of $2.2 billion (its investors include NRG and Google, who are backed by a federal loan guarantee), Ivanpah took four years to develop and uses concentrated solar power, or CSP, to generate up to 377 Megawatts an hour for the state grid. The plant will be at full operating capacity by January.

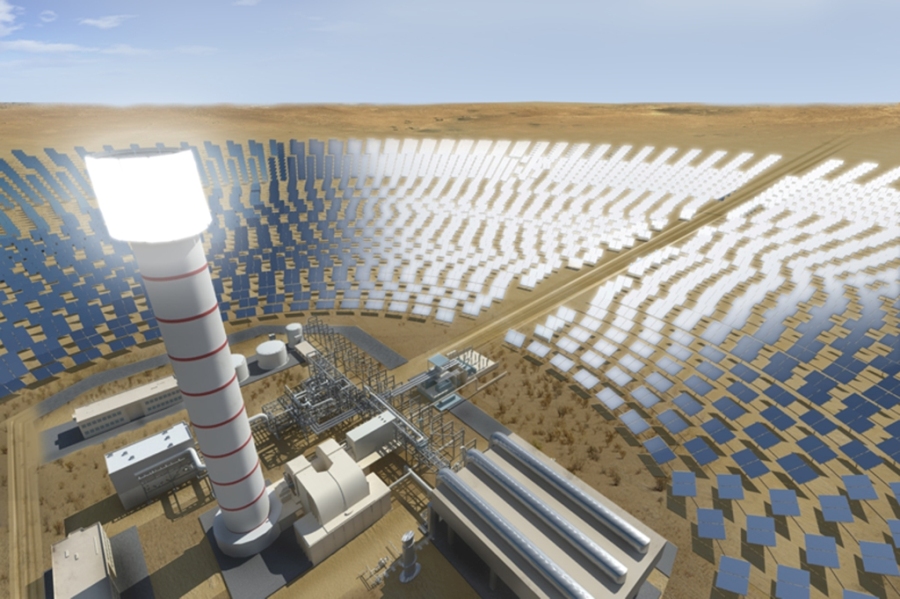

Located on 4,000 acres of now-enclosed public land near the Mojave Desert, the facility features three central towers surrounded by enormous rings of heliostat (sun-tracking) mirrors that direct beams of sunlight onto the towers’ receivers. The receivers generate steam to power turbines, producing energy. You can visit the solar site online to take a slightly nausea-inducing virtual tour of the facility.

Second, in Gila Bend, Arizona, the Spanish corporation Abengoa Solar has recently completed the Solana plant, a $2 billion, 280 Megawatt project. Solana is also thermal solar, but it uses mirrored parabolic troughs to heat tubes of fluid that power a turbine. The plant also stores heat in molten salt batteries that release power well into the night, offering a strong counter-example to the common critique of solar as an intermittent energy source and, therefore, unreliable.

These projects will serve as a proof of concept for the viability of investment in large scale thermal solar, which had lately been second banana to the no-fuss, cheaper photovoltaic (PV) solar panels used on most businesses and homes.

Thermal Solar vs. Photovoltaic

Thermal solar technology requires a large, flat geographic footprint to generate power on a utility scale. Due to this, there has been significant opposition to Ivanpah, as well as other large scale solar projects, for thedisruption they cause to desert habitat. While it’s true that photovoltaic technology is more modular — panels can be installed individually, more or less wherever there’s sun — PV power plants would be equally disruptive when scaled up, and are less efficient at generating electricity than thermal solar. Thermal solar is also less susceptible to the interruptions of passing clouds, and can store and release power for hours after the sun is gone.

So if PV is less efficient and less consistent, why is thermal solar losing ground to it?

Here we get into the foggy area where environmental concerns meet the global market. A PV power plant amounts to a lot of PV panels located in one place. The technology is known and the outcome predictable, making PV a safe and reliable investment.

But in the warm glow of investor funds, Chinese manufacturers in recent years have slashed the cost of production and flooded the international market with PV panels. The influx was so fast, and the numbers so large, that U.S. and E.U. regulators imposed tariffs this summer on Chinese renewables in support of their own renewable sectors, or in deference to the fossil fuel lobby — or perhaps both.

It won’t do to slander photovoltaic as bad and praise thermal as the better choice. Both are crucial pieces to our climate puzzle, serving distinct functions. But what particularly troubles me about PV is its reliance on rare earth metals and the toxic environmental and political processes used to extract them.

Typically, corporations operating mines do not embrace human rights alongside the rare commodities they seek. And humans still have no good ideas about where to warehouse hazardous materials after their utility is spent. So, in anticipation of a future shortage of the necessary materials to produce PV panels, wouldn’t it be wise to cultivate a technology that isn't restricted by materials availability?

A Little Perspective About the Size of Things

To that end, here are two nice, big projects right when we need them. If these plants continue to produce reliable energy with minimal surprises, they may stimulate solar thermal technology to evolve alongside photovoltaics. Jeff Holland, the media contact at Ivanpah’s NRG Corporation, describes the project as “technologically agnostic."

"The price of PV has come down so drastically in the past two or three years, no one could have predicted. But if the economics are right," he says, "we would absolutely do more solar thermal. We’re a pretty diverse company, but [Ivanpah] is going to be our big stake in the ground. We consider it our crown jewel.”

Referring to the molten salt storage technology that Solana is employing in neighboring Arizona, Holland adds: “If we had been planning this a little later, we probably would have included some storage.” Nonetheless, Ivanpah stands as the world's largest solar thermal power producer. To put large in perspective, a word about watts:

A kilowatt is a thousand watts, and a Megawatt (MW) is a million watts. When a power plant is rated in Megawatts, it is the unit of power that refers to its maximum possible output in one hour. A typical American household in 2008 used energy at an average rate of 2 kilowatts per hour.

Arizona, with a population of 6.6 million, is 26th in U.S. energy consumption and 23rd in CO2 emissions. It generates its electricity from a mix of sources, led by natural gas, then nuclear, coal, hydroelectric and mixed renewables, in a negligible 5th place. Challenging this, Solana will serve the needs of 70,000 Arizona households. A nice start, though it still leaves about 1.5 million Arizona households powered by fossil fuels. A notable fact about Arizona: 25% of all energy consumed in the state is from air conditioning (the national average is 6%).

California, meanwhile, is a bigger and more complicated beast. While its per capita energy consumption ranks 47th in the nation, it is the second largest CO2 emitter behind Texas. While it has nearly weaned itself off coal entirely, California is burning a stunning amount of natural gas, and it does major business producing and refining crude oil. The state came up 2 percentage points short of its goal in 2010 to meet 20% of its energy needs with renewables.

With Ivanpah, California’s total solar generation capacity is raised to approximately 3,300 MW. By comparison, the Moss Landing Power Plant, a Monterey Bay plant that burns natural gas, has a 2,560 MW capacity. Unless renewable initiatives like Ivanpah are met with the decommissioning of fossil fuel plants and further emissions cuts, we’ll end up turning the indoor temperature of Arizona down three degrees while California’s Teslas and Leafs simply idle longer on the expressway, releasing less extreme but still steady amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments