As more and more people converge on New York for the Great Climate March on Sunday, Sept. 21, many are telling the stories that led them to march. We hear tales of the impacts of climate change, whether they're the result of an extreme weather event or sea level rise, and tales of those trying to prevent industries such as tar sands, fracking and coal mining from poisoning their water and food sources.

I know why I am marching. I am marching for Kalin Callaghan from the Rockaways. She described to me watching the entire Rockaway peninsula get submerged in water during. The next day, with a baby on her back and child in her stroller, she walked a mile through mountains of sand, overturned cars and buildings on fire.

I am marching because I have gotten to know her and other members of Rockaway Wildfire, a group that came together after Superstorm Sandy devastated their community. They and many others have been waiting, still, for government funds to rebuild and get back into their family homes after almost two years. But as they wait, they hear news that New York University was given over $1 billion for post-Sandy repairs.

I am marching because there are communities in New York City that know that climate change is more than just weather events. To some, climate change means the extra humidity and summer heat that is making mold in their housing developments worse. Roxi Reid, an activist with Community Voices Heard, showed me what seemed to be a never-ending slideshow of mold problems in different apartments. This has been a problem for the past 30 years and has resulted in high asthma rates in her community.

The housing developments in which Roxi used to work are located in the South Bronx, where community members have been running a campaign to stop FreshDirect, a grocery delivery company, from bringing over 100 diesel trucks through their neighborhoods. FreshDirect is trying to receive $127 million in public subsidies to move its headquarters to the Bronx where its diesel trucks would exacerbate not just greenhouse gas emissions but the area's asthma crisis. Local incidence of the disease is five times higher than the national average.

The proposed headquarters would also sit on top of a Native American burial ground, which hits particularly close to home for me since I grew up in Canada, where the vast majority of environmentally destructive projects take place on Indigenous lands. Fossil fuel corporations are constantly proposing to build tar sands projects, fracking operations and coal mines on land without conducting proper consultation or gaining informed consent from the people—most often Indigenous—that live on that land.

It is for that very intentional reason that the People’s Climate March will begin in Columbus Circle. It wasn’t chosen because it was a convenient location. It was chosen as a clear recognition that Indigenous people are on the frontline in struggles against many polluting industries, leading those struggles for the protection of their communities.

Our march will be lead by Indigenous people as well as by young people — particularly those from communities of color and low-income communities. These young people will face the unforeseen impacts of climate change, though they have been shut out of the conference halls in which people are making the decisions that impact their lives.

Despite these closed doors, young people know very well what's going on – and they prove it every day. From UPROSE and El Puenteto Global Kids, the Alliance for Climate Education and many more, New York-based groups committed to youth empowerment have been working every day to turn people out for the march, in addition to the work they do building resilient and strong networks to deal with the impacts of climate change.

These are the same grassroots networks that enabled many New Yorkers to bounce back after Sandy, emerging to provide disaster relief and mutual aid to communities battered by the superstorm. When such crises hit, these formal networks arise through the relationships and friendships we have all worked to build.

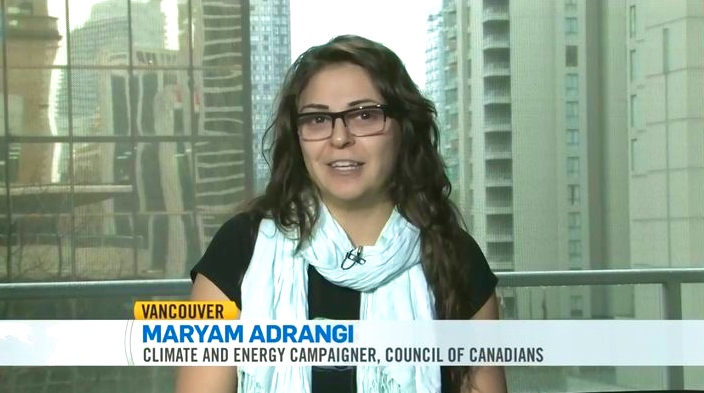

In Vancouver and unceded Coast Salish Territories in British Columbia, where I grew up, we activists work closely with such networks. Urban organizers have, in turn, been able to draw broader attention to more remote pipeline blockades when they're threatened, like when the Unist’ot’en people evicted pipeline surveyors who came to their land in November 2012.

During my time in NYC working to build the march, I’ve stayed up to date on happenings in Secwepemc territory, where a tailings pond was breached at the Mount Polley Mine. I follow email threads about emergency and rapid-response rallies, demonstrations and press conferences. All of this can happen because of the years we've spent building and maintaining relationships with people who are fighting the constant threat of environmental destruction. Friends of mine back home are also organizing around the Climate March, with an action at the Canada-U.S. border to proclaim: “Climate Change Knows No Borders!”

And it doesn’t.

Floods, hurricanes and droughts know no boundaries, nor do the big businesses that are constantly expanding their operations across borders. These corporations destroy land and water. They destroy local economies and jeopardize people’s work. They destroy people’s food sources and their homes. They force people out of their homes and uproot people from their communities — sometimes forcing them to cross militarized borders where they're not legally allowed to claim immigration status, as climate and environmental refugees are not yet recognized. It is for these reasons I march.

I march not because this single day will change everything, but because I know that the stories we hear from new friends and new people will compel us to act. The stories will compel us to be there when the going gets tough — when a company wants to put a pipeline through our land, or when we are forced to leave because we can no longer drink the water. I march because New Yorkers have been using this march as an opportunity to talk to their neighbors, their friends and even visitors like me.

I march for the good friends I’ve made here in New York City who do not have the choice to act — but are forced to do so. I march because there are people who have shown that they are the movement for climate justice. I am joining them because I want to be part of their movement.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments