I’ve written previously about the growing fear among elites that they’ve pushed economic inequality too far. That fear is proliferating, according to a New York Times Op-Ed this weekend by former marketing conglomerate CEO Peter Georgescu. Joined by his friend Ken Langone, founder of Home Depot, Georgescu warns his fellow 1 percenters that “[w]e are creating a caste system from which it’s almost impossible to escape.” The column raises the specter of “major social unrest” if inequality is not addressed.

Georgescu writes:

I’m scared. The billionaire hedge funder Paul Tudor Jones is scared. My friend Ken Langone, a founder of the Home Depot, is scared. So are many other chief executives. Not of Al Qaeda, or the vicious Islamic State or some other evolving radical group from the Middle East, Africa or Asia. We are afraid where income inequality will lead.

In June, Cartier chief Johann Rupert — worth an estimated $7.5 billion — delivered the same message to his wealthy colleagues, telling them that the intensifying inequality and what it portends “keeps me awake at night.” He told his fellow elites that “We are destroying the middle classes at this stage and it will affect us.” Like Georgescu and Langone, Rupert feared unrest and asked, “How is society going to cope with structural unemployment and the envy, hatred and the social warfare?”

But while Rupert only mused about the prospects for continuing to hawk jewelry and the restfulness of his nights amid the tumult, Georgescu and Langone are being proactive. Georgescu writes that he and Langone “have been meeting with chief executives, trying to get action on inequality,” taking advantage of Langone’s tremendous access to business leaders. “You’d be hard-pressed to find a major CEO that wouldn’t take his call,” said a close associate of Rudy Giuliani of Langone in 2012. Georgescu and Langone are telling their patrician peers that if “inequality is not addressed, the income gap will most likely be resolved in one of two ways: by major social unrest or through oppressive taxes.” The word seems to be getting around at the global aristocracy’s water cooler, and Georgescu writes that they “find almost unanimous agreement on the nature of the problem and the urgent need for solutions.”

It is remarkable that Langone is partnered with Georgescu on this crusade for social justice. Langone served on the board of a leading populist philanthropy group called the New York Stock Exchange, and his deep concern for the downtrodden led him to chair that gang of do-gooders. He’s a longtime generous contributor to Republican presidential candidates who have been on the front lines of the battle to institute supply-side and neoliberal economics. “[T]here’s nobody better than him,” Rudy Giuliani said last year about Langone’s prowess as a bundler for GOP politicians. And when he isn’t giving money and raising funds for the political friends of big business, Langone gives the invaluable gift of his careful insight, last year comparing progressives’ attention to income inequality to Hitler’s political project in 1933.

The only thing Langone had right was the year: 1933. It was in that year that President Franklin Roosevelt took office at the height of the Great Depression, inequality peaked to record levels, and fears of revolt circulated among that era’s fat-cat elite. Capitalism, unreined during the 1920s, had hit another of its cyclical failures, this time its worst yet. The powerful feared revolution, and the New Deal constituted a sort of bargain made between capitalists and the people: A bit of socialism to save capitalism from itself.

That year, John Maynard Keynes issued an open letter to the newly inaugurated Roosevelt in the New York Times, whose two opening sentences of the more than 2,500-word manifesto defined the stakes and posed revolution as the price of failure of severely altering capitalism as it was practiced. Keynes was no radical. He urged the new president to work “within the framework of the existing social system,” that is, to reform capitalism without allowing it to be abandoned or abolished.

It was later revealed that when in 1938 a year-long recession threatened the gains made against the Depression, as conservative Democratic legislators urged severe cuts in public works and farm aid, Roosevelt feared revolution. “The president remarked that this would mean calling out the troops to preserve order,” wrote a cabinet member in his diary. “It might even mean a revolution, or an attempted revolution.”

Georgescu and Langone’s mission perhaps finds its best Depression-era analog in Joseph Kennedy, the millionaire father of the eventual president John F. Kennedy, who said of the Depression that “in those days I felt and said I would be willing to part with half of what I had if I could be sure of keeping, under law and order, the other half.” Kennedy, like many (but hardly all) of his elite colleagues, knew that capitalism had to be bridled if it was to survive. “I knew that big drastic changes had to be made in our economic system,“ he later told Joe McCarthy. “I wanted him in the White House for my own security.”

Langone and Georgescu — like Kennedy, Roosevelt and Keynes — are urging another radical reformation of capitalism so that truly radical change doesn’t come. But they make serious mistakes in their judgment and prescription. They warn of “punitive,” “oppressive” levels of taxation — an 80 percent upper marginal rate with a low upper-bracket threshold — as a potentiality if their upper class doesn’t self-correct. But those levels of taxation wouldn’t be levied to punish or oppress; it would be to redistribute their collected wealth to the rest of us. Sharing isn’t being punished.

Second, they propose that the change has to come from the capitalists themselves, that some sort of agreement would be reached to willfully raise wages significantly in the absence of governmental mandate. This seems to ignore fundamental laws of competition. Even if some degree of consensus was reached, any dissenters would gain a fantastic advantage over their competitors in the form of profit levels far exceeding those of their rivals. It would be asking corporations to enter the ring with one arm tied behind their back and face off against unrestrained competitors.

They seem to know this and concede that “the most obvious choice is our government” to guide and enforce the change. Every major gain against the greed that animates capitalism has been implemented by mandate: the minimum wage, the right to collectively bargain, the 40-hour work week, the weekend, and a host of other rules of the road that marked the post-war economic and civil peace.

“But the current Congress has been paralyzed,” they acknowledge.

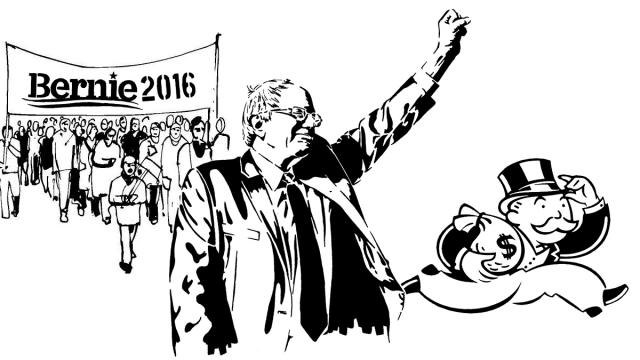

And why is it paralyzed? Has President Obama not faced resistance to his efforts to restore a modicum of equality by politicians bought by the very class to whom Georgescu and Langone make their appeal? They might try not shoveling hundreds of millions of dollars into the coffers of “pro-business” politicians who dutifully defy virtually any tax increase, regulation, and pro-union effort. Bernie Sanders forbids big-dollar donations of the sort sent to pro-business politicians of both parties, but they might consider, as I argued previously, working to elect him as a bulwark against the upheaval they fear. Sanders is merely proposing that we return to the bargain achieved in the 1930s and post-war years. I’m sure they’d scoff at the idea, but it’s not crazy. What’s crazy is to believe that capitalism can be saved by the capitalists themselves, like all lions agreeing to hunt without claws.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments