It was late September 2011, and Radiohead was about to play a surprise concert in Zuccotti Park in Downtown Manhattan. The reason? Occupy Wall Street. Hundreds of protesters had been camping out in the park for two weeks, and a rumor flew around the encampment that the British band was going to do a pop-up set to rally the crowd.

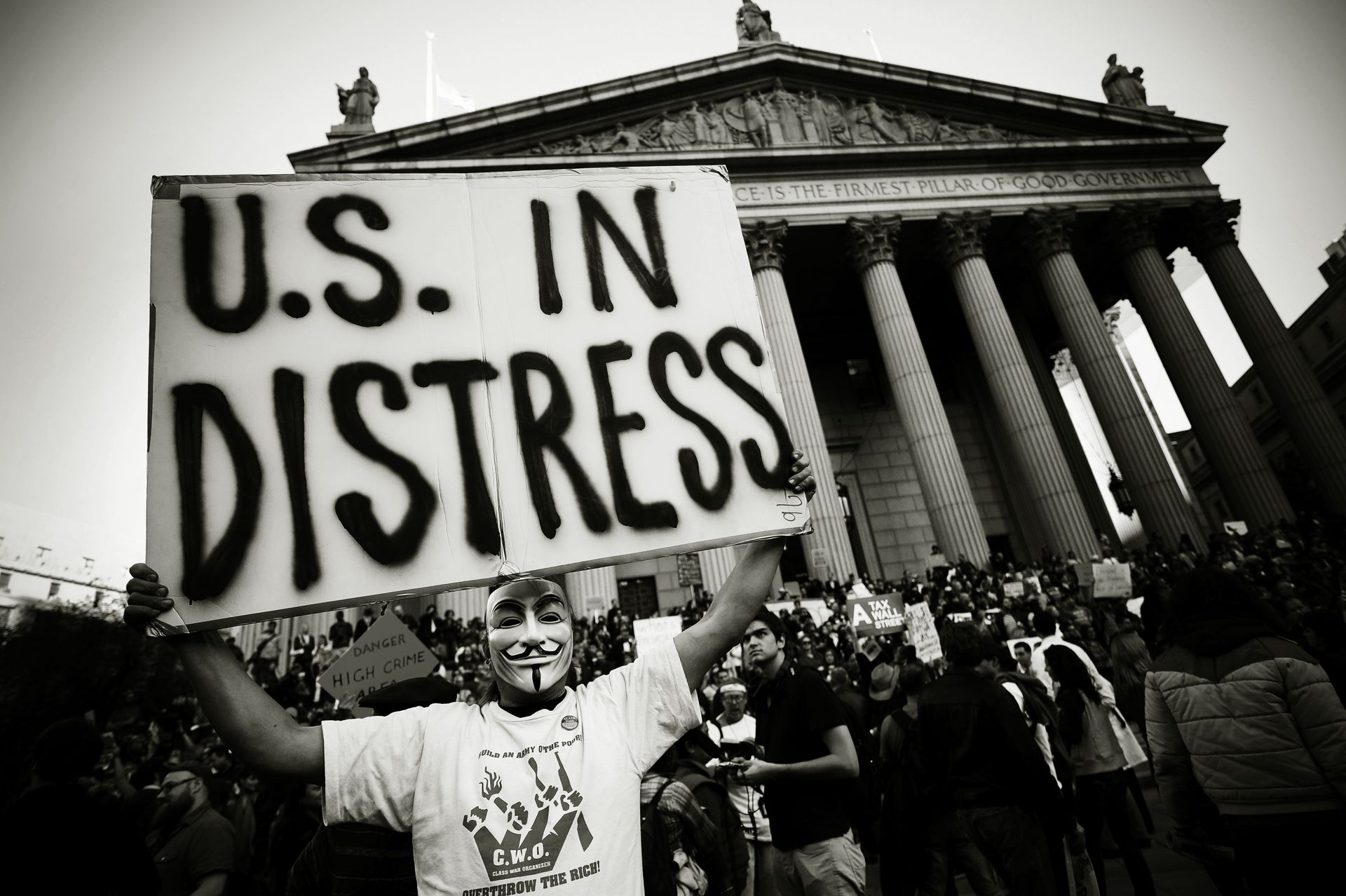

Occupiers were angry at the state of the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. They rejected the deep inequalities that capitalism had fostered. In the United States, President Barack Obama hadn’t delivered on the message of change he had promised — he hadn’t even jailed the bankers responsible for the meltdown. Governments around the world were shoring up financial institutions while leaving their citizens behind.

And now, Occupy Wall Street was even angrier: The weekend before, the New York City police had arrested some 80 protesters — and hit some of them with pepper spray.

Radiohead was the biggest sign of the support for the movement yet. “Radiohead will play a surprise show for #occupywallstreet today at four in the afternoon,” Occupy organizers wrote in an email to supporters. Hundreds of fans descended on Lower Manhattan expecting to catch the show, swelling the already sizable crowd at Zuccotti.

Except Radiohead never appeared. The concert was a hoax. The episode seemed to show that Occupy was a disorganized, anarchic mess. No one can even agree, nearly a decade later, who started the rumor.

Just seven weeks later, police cleared the park and the protest ended. In the short term, the movement appeared to have failed.

“It will be an asterisk in the history books, if it gets mentioned at all,” columnist Andrew Ross Sorkin wrote in The New York Times on September 17, 2012, the one-year anniversary of Occupy’s kick-off. He acknowledged Occupy’s role in creating a public conversation about inequality, but otherwise dismissed the movement as “a fad.”

But today, Occupy Wall Street no longer looks like such a failure. In the long run, Occupy invigorated ideas and people that influence today’s American left and Democratic politics.

“Occupy was in many, many ways a shit show,” Nicole Carty, a Brooklyn activist who was a facilitator at Occupy, told me. “But it deserves props, it really does, for unleashing this energy.”

Occupy was the birthplace of some left-wing ideas that have gained mainstream traction: Its “99 percent” mantra, which decried the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few at the expense of the many, has endured. It animated the rise of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and the resurgence of the Democratic Socialists of America, and it is in ways responsible for the some of the most prominent ideas in the Democratic Party right now: free college, a $15 minimum wage, and combating climate change. It was also a training ground for some of the most effective organizers on the left today.

I spoke with more than three dozen people — former members of the Occupy Wall Street movement, journalists who covered it, and people who are currently active in socialism and on the left — about how Occupy Wall Street shaped the world we live in. The tents in the park are gone, but many elements of Occupy have proven to be an enduring success.

“Screaming at the world”

More anarchist than socialist, Occupy Wall Street was a nominally leaderless movement that refused to lay out specific demands. That’s what made Occupy unique — and part of what ultimately led to its demise. As journalist Nathan Schneider, who covered Occupy for outlets such as The Nation and Harpers and later wrote a book on the movement, put it, Occupy “subverted itself and imploded according to its own logic.”

To the degree that any one group can be considered responsible for Occupy Wall Street, the movement got off the ground when the Canadian magazine Adbusters called for 20,000 people to “flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street for a few months” starting on September 17. They also attached the hashtag, #OccupyWallStreet, and made a poster showing a ballerina atop the Raging Bull on Wall Street. The hacker group Anonymous helped spread the message via blogs, Twitter, and YouTube.

Organizers held general assemblies in the weeks leading up to the occupation itself. During an August outreach meeting at the Writers Guild of America East offices in New York, protesters conjured up the “we are the 99 percent” slogan that would become emblematic of Occupy. It referred to the fact that 1 percent of the United States’ population took in a disproportionate amount of income, wealth, and power, leaving comparatively little for the rest — the 99 percent.

The concept of the 99 percent vs. the 1 percent wasn’t a new one. Columbia University economist Joseph Stiglitz, for example, had explored it in a piece for Vanity Fair earlier that year. Within the context of Occupy, some credit anarchist and anthropologist David Graeber with the refrain, but as with so many occurrences within Occupy, there’s no single version of events.

Georgia Sagri, a Greek performance artist, told me she came up with the “we are” part of the slogan and Graeber the “99 percent.” Others say the idea was collaborative. Ultimately, it distilled a precise way of talking about the message of Occupy and spoke to the effects of inequality so many people were feeling. Organizers began to hand out fliers that read, “We, the 99 percent,” the slogan’s first iteration.

The image it provoked was an evocative one: It pitted the very upper echelons and wealth and power against the masses, and it set up a framework for thinking about how the political economy works. Later in August, a “We are the 99 percent” Tumblr appeared, in which hundreds of people would post pictures and stories explaining their struggles.

The rallying cry allowed Occupy to be much bigger than the protests themselves. It’s still being used today — for example, in Sanders’s “For the 99.8 Percent Act,” a proposal to dramatically expand the estate tax. And the phrase has cultural currency: The “one-percenters” is a term regularly used in conversations and articles about inequality.

“Occupy was an uprising. It was an uprising of the 99 percent, those who are left out of politics, who don’t have economic opportunity, against the 1 percent, which is increasingly consolidated,” said Marisa Holmes, an anarchist who was an early organizer of Occupy.

Occupy’s project is better described not in terms of demands but instead grievances. The initial demand that Adbusters ad suggested was the creation of a presidential commission to end the influence of money over representatives in Washington, DC, but that was quickly abandoned, and while organizers debated on what their demands should be, they never landed on a consensus. The demands working group, I was told by multiple people, was one of the most hated groups at Occupy.

“People during Occupy were right not to make a list of 10 demands or be easily satisfied, because what they did was they blew open the options that people could think about,” said Sarah Leonard, one of the producers of the Occupy! Gazette during the encampment and now executive editor at the Appeal.

The point was to name the enemy.

“It was a bunch of really pissed-off people screaming at the world, and what they said wasn’t always coherent, but they were expressing a deep discontent with the way that things were,” Josh Harkinson, a journalist who covered Occupy for Mother Jones, said.

Eric Foner, a Pulitzer-winning historian and retired Columbia University professor, put the movement in historical context: “Occupy Wall Street did what radical groups throughout American history have tried to do, some of them have succeeded, some of them haven’t, which is to change the discourse,” he said.

However, he added, “Occupy Wall Street, like many radical movements, was much better in critique than in political agenda.”

The lack of agenda was what drove Andrew Ross Sorkin’s skepticism of Occupy in the New York Times in 2012 — a view he continues to hold today.

“It didn’t change policy or have the force that the Tea Party did, for example, which was its analogue at the time,” Sorkin told me in an email. “Having spent time myself in Zuccotti Park covering the movement, I would contend, at least in its early stages, it very clearly was about breaking up the banks, putting executives in jail and implementing banking regulation. None of that happened. There was a lot of infighting about what the group’s demands should be and its goals were amorphous.”

Occupy was a failure. It was also a wild success.

Occupy Wall Street, at least in its physical manifestation, came to an end in the early hours of November 15, 2011, when police raided Zuccotti Park. In the days and weeks to come, some protesters would linger, and Occupiers would take their activities elsewhere. Occupy was partly credited with pushing lawmakers on a so-called “millionaires’ tax” passed in New York soon after the encampment ended. But by and large, the movement was viewed as over — and as a failure.

The Occupy movement “has spiraled into irrelevance and relative obscurity,” HuffPost political and pop culture analyst Andy Ostroy wrote in May 2012.

Max Berger, a former Occupier, recalled journalists in Occupy’s aftermath asking him whether the movement had failed. “It depends on what we do now,” he said he told them. “It’s a beginning, and if we don’t do anything else, then yeah, it’s a humongous failure. But if it’s the beginning of an era, then no, it’s just the supernova that gives rise to all these other things.”

In a lot of ways, it did turn out to be the beginning of a new era.

Many of those I spoke with connected the Fight for 15, a national movement for a $15 minimum wage and union rights, to Occupy. New York City fast-food workers walked off the job in protest for higher wages a year after the first Occupy protests. It was orchestrated by a number of community and civil rights groups, including New York Communities for Change, a community coalition and an early public backer of Occupy.

Strikes and militancy have deep roots in the labor movement, but as journalist Sarah Jaffe in her book, Necessary Trouble, noted, Occupy had “added vigor” to labor campaigns throughout New York and had galvanized them to make bigger, bolder demands.

“We needed to be more aggressive and direct-action oriented toward how we were going to make our demand and hopefully win, which is not dissimilar from what Occupy was doing in terms of being more aggressive, taking the streets, taking arrests,” said Jonathan Westin, now executive director of New York Communities for Change.

Fight for 15 claims that it has won raises for 22 million people. New York City’s minimum wage was raised to $15 an hour at the close of 2018, and the idea has made its way into the Democratic Party’s bloodstream. After some wrangling and a push from Sanders, the party included a $15 minimum wage in its 2016 platform. It is now a mainstream position for many Democrats.

Occupy has also played a part in pushing forward the conversation around student debt. Millions of students had turned to the hope of higher education to lead to economic success, only to be left with thousands of dollars in debt and few well-paying job prospects. For-profit colleges seemed to be actively scamming students and the government.

In the months after Occupy, a group rooted in the movement marked “1T Day” of student debt hitting the $1 trillion mark. Former Occupiers also launched Strike Debt! and subsequently published The Debt Resisters’ Operations Manual, a book on the debt system and how to fight it, and created a project called the Rolling Jubilee. The plan behind the Rolling Jubilee was simple — and smart: Organizers raised money to buy delinquent debt that financial institutions often sell for pennies on the dollar. Instead of trying to collect that debt, they forgave it. Through a telethon and online videos, Rolling Jubilee was able to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars and cancel millions of dollars’ worth of debt.

Alumni from that went to the Debt Collective, a union for debtors that has helped students launch debt strikes, such as former students of the now-defunct for-profit institution Corinthian Colleges. The attention the Debt Collective drew to the issue of student debt, including for those who took out loans to attend institutions that were fraudulent or broke the law, resulted in millions of dollars of loan forgiveness. It propelled regulations to protect student borrowers against misleading and predatory practices.

“It was born of Occupy, but we couldn’t operate within Occupy’s demandless constraints,” Astra Taylor, one of the Debt Collective’s founders who along with Leonard put together the Occupy! Gazette, said of the movement.

The conversation around debt right now — and specifically student debt — is front and center. Sanders in 2016 campaigned on a message of free college, and the majority of the Democrats running in the 2020 presidential primary back the idea or something similar.

Calls to break up the big banks and bring back Glass-Steagall, a Depression-era law that separated commercial and investment banking but was repealed in 1999, have roots in Occupy as well.

Alexis Goldstein, now at progressive nonprofit group Americans for Financial Reform, told me that when she first brought up Glass-Steagall at an Occupy event, many people there didn’t know what it was. She started holding teach-ins about the law and eventually became part of a group called Occupy the SEC. That group sent a more than 300-page comment letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission on the Volcker rule, a regulation included in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill that bars banks from conducting certain investment activities.

“The media ate it up, because they were like, ‘Oh my God, Occupy Wall Street can read!’” Goldstein recalled. Occupy’s comments were cited more than 200 times in the footnotes of the final rule.

Some of the movements that grew out of Occupy Wall Street were more directly similar, like Occupy Homes, an effort to try to help Americans hit by foreclosures and evictions during and after the crisis, and Occupy Sandy, which helped communities affected by Hurricane Sandy after it hit the East Coast in the fall of 2012.

Occupy was also a launching pad for several people who would go on to become influential figures on the left.

“There’s a generation of direct action trainers and organizers who really cut their teeth in that moment,” Ingrid Burrington, who was part of Occupy’s “think tank” discussion group and is now a writer, told me.

Nelini Stamp, a former Occupier, now heads strategy and partnerships at the Working Families Party and was part of Cynthia Nixon’s New York gubernatorial campaign. She told me she assumed Occupy would be a bunch of “white kids in a park talking about a revolution.” But after heading to Zuccotti Park in 2011 and after seeing it for herself, she decided to stay.

“Everything that I learned to do, I learned it by being thrown into the situation,” Stamp said.

Max Berger, who sometimes jokes that he is a “housebroken Occupier,” got his start in politics well before Zuccotti, when he took a semester off of college to intern for Howard Dean’s presidential campaign. Since then, he’s hopped among political organizations and social movements before and after Occupy.

“What Occupy did was it opened up a tremendous amount of space, it called a lot of things into question that it itself could not answer,” Berger said. “What’s happened since then is a new generation of people rushing in to answer those questions.”

Berger is one of the founders of Momentum, a group that trains organizers of social movements. Among the movements it’s trained and helped launch are rising stars on the left today: Sunrise, a major backer of the Green New Deal, and If Not Now, a Jewish progressive group that is opposed to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory. (Berger is also one of the founders of If Not Now.)

Berger is also one of the founders of AllOfUs, a political action group that folded into Justice Democrats, which is one of the animating forces behind Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s upset victory over incumbent Joe Crowley in New York. Waleed Shahid, who is now at Justice Democrats, also spent time at Momentum and was one of the AllOfUs founders with Berger, who has since left both Momentum and Justice Dems.

“Occupy Wall Street created a bunch of movement infrastructure in the form of new associations, new organizations, new models for thinking about social movements, new communications strategies, new movement spaces, and in that way, it left more than was there before it started. And the more that it left there has been useful to subsequent movements,” said Jesse Myerson, a former occupier who most recently spent two years in Indiana with the Indiana-based community group Hoosier Action.

Jonathan Smucker founded Beyond the Choir, a movement training group that predates both Momentum and Occupy, and is the author of Hegemony How-To: a Roadmap for Radicals. Much of his work is focused on the importance of social movements speaking to broader audiences and avoiding just talking to themselves. Beyond the Choir has helped Sunrise, If Not Now, and AllOfUs, among others.

Smucker, who told me that he was initially skeptical, went to New York after he saw Occupy take off. He wound up staying for a year to try to help build movements and train people. He acknowledged that work might not have always been so visible. “Occupy had a front stage and a backstage,” he said, “and I think a lot of the more politically oriented folks were in the backstage and behind the scenes.”

For many former Occupiers, life has been more complicated. Cecily McMillan, for instance, was arrested at an Occupy protest months after the original encampment and was subsequently charged with and convicted of assaulting a police officer as he tried to lead her out of the park. She was convicted of a felony and jailed at Rikers Island for 58 days. She wrote a book about the experience and now lives in Atlanta. When I asked her what she’s up to now, McMillan replied, “Actively surviving recidivism, which is a lifelong fucking endeavor that is really fucking horrific.”

There was some disagreement among those I spoke with as to how much Occupy contributed to what’s happening on the left and, specifically, within socialism today. Those more immersed in Occupy tended to see it as a major force, while others on the periphery or whose involvement in the left is more rooted in current events downplayed it. A number of people pointed out that multiple other social movements, especially the Movement for Black Lives, have been essential.

“If it wasn’t for Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter as a movement and the overall Movement for Black Lives, we wouldn’t be having the conversations around race and capital that we are right now,” Stamp said.

Charles Lenchner, who was on the Occupy tech committee and helped create an email list for it, and Winnie Wong, who helped start the sustainability working group at Occupy, created Ready for Warren to push Sen. Elizabeth Warren to run for president in 2016, and that eventually turned into People for Bernie in support of the Vermont senator. (She is now a senior political adviser to Sanders’s presidential campaign.) In its beginnings, People for Bernie folded in Ready for Bernie, a Facebook-based group created by Justin Molito, a WGAE organizer who was at that early “99 percent” meeting. He is still one of the administrators of the Occupy Wall Street Facebook page.

“There’s just no doubt that the Occupy movement helped create some more space for an openness to Bernie Sanders’s message,” Molito said.

Bianca Cunningham, who is co-chair of the steering committee of Democratic Socialists of America in New York, told me a story about how her path to the labor and socialist space was indirectly influenced by Occupy. When she was considering unionizing at a Verizon Wireless store where she worked in Brooklyn, a union rep who came to speak with her told her that he had been at Occupy, which in her eyes gave him more credibility. “When I left the meeting, I called my coworkers ... and I was like, ‘This guy’s like the real deal, he slept in the park in Occupy,’” she said.

“We feel like we are definitely standing on the shoulders of the people of Occupy who started the conversation about this critique on Wall Street, this critique on capitalism, this critique of the economy, and really made it a topic of conversation,” Cunningham said.

Matt Bruenig, founder of the People’s Policy Project and respected voice on left-wing policy matters, on the other hand, told me that Sanders is “100 times more significant” than Occupy in his eyes. Bhaskar Sunkara, who founded socialist magazine Jacobin in the early 2010s, said that Occupy “helped define the politics of a generation” but also thought Sanders was more influential in shaping leftist politics right now.

In some ways, the projects of socialism today and Occupy Wall Street are by definition at odds. Many on the left currently are engaged heavily in elections — celebrating the rise of figures such as Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, Ocasio-Cortez, and Sanders. Occupy resisted the electoral process.

“My entire generation ... believes that the Democratic Party is the electoral vehicle through which any sort of left or socialist politics will exist,” said Sean McElwee, cofounder of Data for Progress and an outspoken figure on the left who takes credit for, among other things, the #AbolishICE movement. He hosts a weekly happy hour for progressives in New York.

Jumaane Williams was the first elected official to back Occupy as a member of the City Council at the time. He was arrested during an Occupy protest and pushed by a police officer during an Occupy anniversary event. Now, Williams was just elected New York City public advocate and identifies as a democratic socialist.

“There’s so many people in Occupy who are working in government offices, who are working for congressional candidates, who are working for organizations that are organizing around these issues,” Williams said.

Not everyone agrees that winning elections is the right way to go.

Malcolm Harris, a former editor at the New Inquiry and author who was arrested at Occupy, told me that in his view what democratic socialists are asking for isn’t actually that radical and that what Occupy understood better is that “the whole system has to go.” He compared it to the “streetlight effect,” where a man comes upon another man looking for his keys under a streetlight. After helping him look for a while, the man asks whether he’s sure he lost them there, and the guy responds that he’s not — he’s just looking where the light is, not where the actual solution to his problem is.

“That’s what democratic socialists are always doing, is they’re looking where the light is,” Harris said. “They’re looking where they think they can make some advantages, where they can pull together some wins. They’re not looking at history and what is actually important in terms of the tensions and fractures within society.”

Economist Richard Wolff, the author of Understanding Marxism, seems thrilled at the interest in leftist politics and, personally, in the level of attention his own work has gotten in recent years. But, he acknowledges, a lot of the young people he interacts with are more anti-capitalist than they are socialist.

“What they say about socialism is really, I don’t want to be unfair here, but I’ll say it: It’s not very well informed,” he said. “And it’s not their fault. There’s been nothing to teach people about the varieties of socialism.”

“The left is so damn white”

While there were people of color involved, Occupy Wall Street was a majority white space. It’s something that socialism and the left have not been able to shake. That’s not to say that there aren’t people of color who are and were leaders of the movements, but there are still divisions about how to talk about race and class and what policies to put forth to address not only economic inequality but racial inequality as well.

“Bernie has the best analysis, but, like Occupy, is very bad on race,” said Nicole Carty, another former Occupier who is now a trainer at Momentum. Carty has also been active in the Movement for Black Lives.

Sanders tends to say that the socialist policies he put forth — Medicare-for-all, free college, an expanded welfare state — will benefit communities of color the most and, therefore, address racial inequality. Sanders has shifted his stump speech on inequality and included more traditional Democratic themes in the way he talks about specific demographics and racial inequities. But he hasn’t been able to shake the reputation that he’s still not great at communicating on race.

“When I’m listening to a speech, I don’t hear what the actual racial inequities in health care are,” Stamp said.

“Femmes, women of color, women, people of color experience oppression through lived experience,” Cunningham said. “That creates a sense of urgency that sometimes I feel like is lacking in mostly white spaces.”

There’s not widespread agreement on the matter. Sunkara told me he’s “somewhat dismissive of those vague concerns” around race. “As far as I’m concerned, economics is actually the primary anti-racist tool that we have,” he said.

The lack of diversity manifests itself in a lot of ways, including the policies and positions the left pursues. Lyle Jeremy Rubin, an Afghanistan war veteran and member of DSA in Rochester, said that while “anti-capitalist politics is ubiquitous” right now, anti-imperialism is not.

“The fact that the left is so damn white, they’ve failed to really see the full burden and weight of imperialist relations and the role that the US actually plays, particularly from the perspective of people of color from around the world who are on the wrong end of our weaponry and even our overall economic machine,” Rubin said.

Michael Premo, who took part in both Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Homes and now is a documentary filmmaker, echoed the sentiment. “There is always going to be an elephant in the room that we have to deal with. The fundamental issue for me is that we live on stolen land, and this country was built by the forced labor of slavery, and we don’t reconcile with those two things,” he said.

“Everyone ended up sticking around”

It’s much too early to figure out exactly how much of a lasting impact Occupy had — and perhaps even more so how much of an effect this current rise of socialism in the US will have overall. But speaking with former Occupiers, there was a sense that they thought of the journey of as much of a personal one as they did political.

“Occupy changed me, and it changed lots of other people, and it made us do the work of activism and the work of organizing better, and we took that to so many different and varied things,” Goldstein said. “And that is invaluable.”

Despite its failures, Occupy Wall Street wound up being sticky, maybe even thanks — just a little bit — to that Radiohead rumor in September 2011. I asked Harris, who claims to have been behind the hoax, if people were upset and left once they realized Radiohead wasn’t coming. “Everyone ended up sticking around,” he said, “because no one wanted to admit that they were just there for the concert.”