RamKumar Gorai marched with the freedom fighters in 1947, demanding the British leave India. He was all of 21 then. At age 60, when he went to claim his legitimate pension, he was shocked to be asked that he pay a bribe to ensure its speedy disposal. Then a staunch Indian National Congress party supporter, it was the day he shifted his allegiance to the Aam Admi Party, India’s newest political outfit shaking up the elections this month.

“They seem to truly focus on the people,” Gorai says, echoing what a majority of his country people these days are saying. “They are against corruption and just for this alone I am on their side.”

New hope

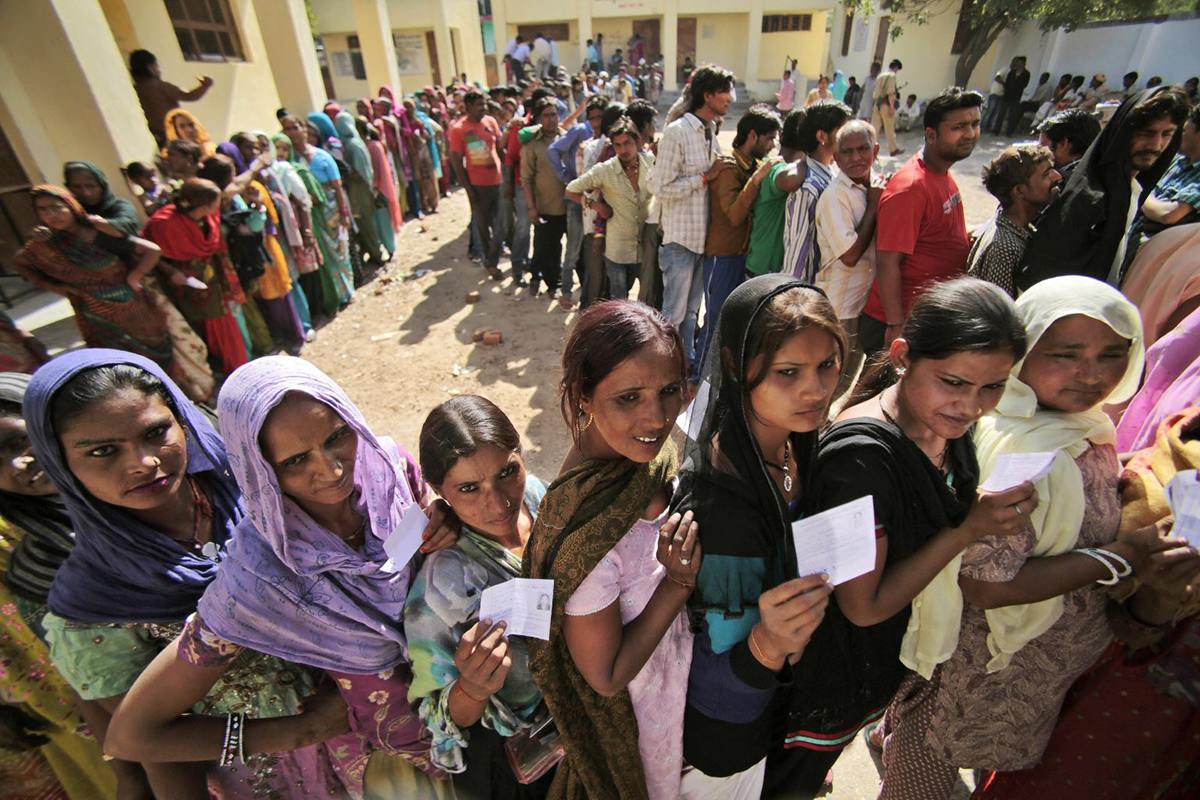

As the world’s largest democracy goes to the polls this month, the Aam Admi Party – or Common Man’s Party – seems to have emerged as a new hope promising a corruption-free future. Launched in November 2012, the party has in a short time made big strides appealing to Indian voters with its focus on eliminating bribery, graft and other forms of everyday political corruption – while promising that “common man’s” needs and demands will form the backbone of its agenda.

Led by Arvind Kejriwal, the party unexpectedly won the 2013 Delhi legislative assembly election – which made Kajriwal Delhi’s chief minister. India’s electorate now seems infused with fresh hope as the party draws support from old and young alike – including open support from students of the country’s premier institutes and intelligentsia.

V. Balakrishnan, a former board member of the NYSE-traded software giant Infosys, is among Aam Admi’s high-profile supporters. But average workers are at its core. As Kartik Deuti, a teacher from Kolkata, says: “It’s a myth that corruption affects only the poor. Its effects might be more obvious in the economically weaker section, but corruption affects all.”

Deuti says he is impressed by the anti-corruption hotline the party helped establish, which people can call to report demands for bribes made by government officials.

A believer in politics where “the leader and public play equal roles,” the 45-year-old Kejriwal isn’t your average Indian politician. A mechanical engineering graduate from India’s premier Indian institute of Technology (IIT), he was part of Team Anna, a strand of the Indian anti-corruption movement that also involved another Magsaysay laureate, Kiran Bedi.

Kejriwal is no stranger to the history of corruption in his country. As founder and leader of the grassroots movement Parivartan – which launched the India Against Corruption movement, using right-to-information legislation to unearth scandals and the misuse of public funds – he was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay award and donated the prize money to establish the Public Cause Research Foundation in 2006.

“Change begins with small things”

From the start, the Aam Admi Party promised to operate differently from those currently in power. For example, to ensure access to the public, Kejriwal holds public hearings. At the first hearing, held in January of this year, hundreds came with application letters regarding problems they wanted fixed – and amid the chaos of so many attendees, lots of them had to be turned back.

Rakhi Rai, who braved the crowds, said, “My application was taken by the party volunteers. I want the open drain in our locality repaired. It hasn’t been done yet. But I suppose it will in time.”

The party is learning. In Benares some days later, things were much better organized; at the hearing, volunteers gathered up people’s questions and application letters before the party leaders started speaking. Kejriwal talks about establishing a new order in India where education is given priority attention. He promises to strengthen government schools so that children from every strata of society can compete at equal levels. “This will wipe out the need for the reservation of seats that cause so much resentment,” he says.

Yet while the party steadily develops a strong support base, its resignation after only a few days in power last year didn’t sit so well with many who had voted for them. Ruma Ghosh, a school teacher, was bitterly disappointed. “You have to give time to bring in improvements,” she says. “Impatience will not serve a purpose.”

Kejriwal, in an interview, said, “Our intention was not to keep sitting in the Government when we could not even do what people sent us to the Assembly for.”

Common criticisms

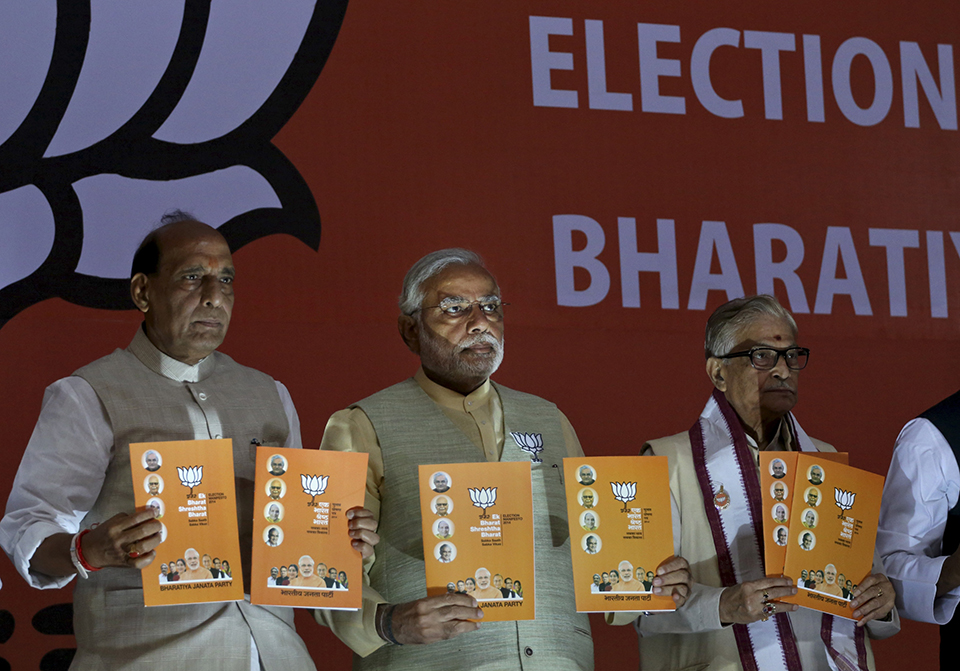

With prominent intellectuals and personalities lending it popular support, the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) with Narendra Modi as its prime ministerial candidate poses tough competition for Aam Admi. Among the criticisms of the upstart party being leveled by the establishment include its lack of a coherent formula to help the country deal with corruption.

“Talking about leveling corruption isn’t the solution,” says Dr. Samaresh Guchhait, a physicist at the University of Texas at Austin, who is closely following the elections this month. “I want to see concrete steps that they will take. Besides, as a chief Minister in Delhi, [Kejriwal] should have implemented something to justify our faith.”

Indeed, the lack of a strong, concrete manifesto and plan for the country’s growth might be the Common Man Party’s Achilles heel – if critiques like Guchhait’s are indication of broader, mainstream sentiment.

As a New York Times story reported, the Congress Party may promise projects including 100 days’ work and other labor schemes for the economically deprived, but rampant corruption ensures that people often don’t even get the pay they worked for.

Transparency International says India is ranked 94th among 177 countries on the corruption index. It’s these rankings that citizens today want changed, and the Aam Admi Party seems to hold a key to that development. The question is now: can the party win votes and deliver?

Follow the author Paromita Pain on the Commons or on twitter at @ParoP

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments