Good criminals don’t leave calling cards at the crime scene: they cover their tracks. In the hit movie Ocean’s Eleven, a group of cunning thieves meticulously organize and pull off the heist of a Las Vegas casino. Now, some of America’s most cunning and powerful real-life individuals may have pulled off a major heist of the 21st century – the systematic pillaging of the U.S. Postal Service and its assets.

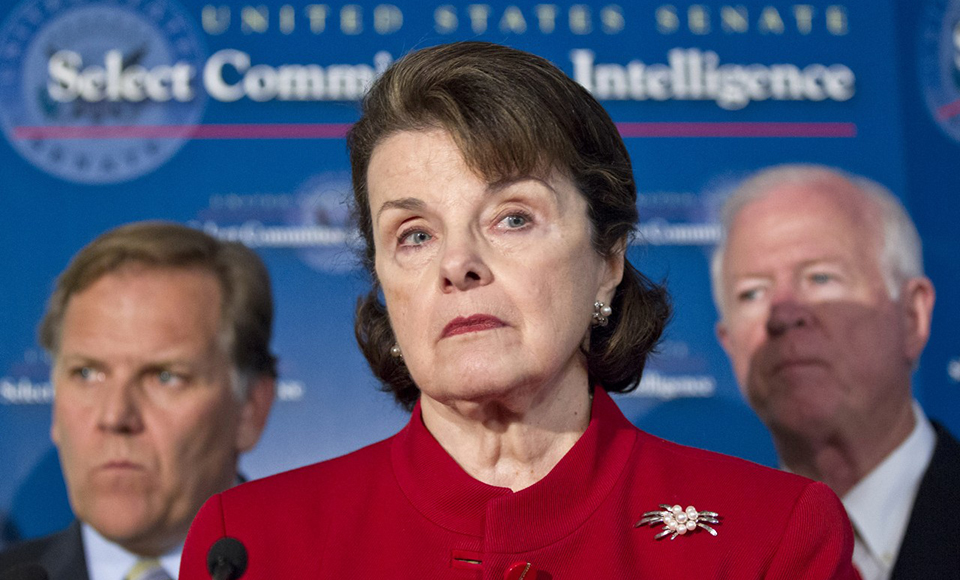

Our cast of characters includes California senior U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein; her UC Regent husband Richard Blum, who is the president of Blum Capital and chairman of the board for CB Richard Ellis (CBRE), the largest commercial real estate developer in the world; and Tom Samra, the multi-millionaire chief of the U.S. Postal Service’s facilities management division.

After a crime, good investigators sift through the available facts to make a case for what happened — facts that clearly don’t pass the smell test, but don’t fit neatly together, either. The facts below, many of which emerged from investigative journalist Peter Byrne’s 94-page book Going Postal (2013), raise serious ethical and legal questions about a spate of transactions that enriched all three individuals at the expense of the U.S. Post Office’s survival.

Did Feinstein Abuse Her Office?

As chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Dianne Feinstein reinserted herself in the national spotlight last week by calling out the CIA’s spying operations on her committee while it was researching torture allegations under the Bush administration. Feinstein, 80, is avociferous defender of the NSA’s domestic spying program and its bulk collection of private citizens’ data – which makes it the more ironic that she flew completely under government radar while arguably abusing the power of her office to secure lucrative contracts for her husband’s business and, thereby, her household.

Between 2001 and 2005, Feinstein vetted and approved $1.5 billion in defense contracts for Perini Corp and URS Corporation – both owned by her husband, Richard Blum. In 2009, Feinstein successfully introduced a bill that routed an additional $25 billion to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), some of it for the purpose of marketing foreclosed property owned by banks that had gone under with the housing and markets crash. In a curious twist, CBRE later received a $108 million FDIC contract to market foreclosed property.

Byrne’s research also found that in 2007, Feinstein directly intervened in a development project in which her husband’s company stood to benefit. In 2005, Lehman Brothers had approved a $252 million loan to the real estate partnership Heritage LLC. One member of the partnership was the Miami-based Lennar Corporation, which planned to develop 3,723 acres of real estate for commercial and residential property at the El Toro Marine Corps Airstation in Orange County, California. Lehman Brothers’s bankruptcy filings later revealed that CBRE was in charge of performing “due diligence” for the El Toro project, which included appraisals for non-residential property.

In 2007, when the U.S. Post Office was planning to build a mail processing plant on a $7.5 million, 26-acre plot in nearby Aliso Viejo, Calif., the city’s mayor wrote a letter to Senator Feinstein complaining that the plant would be too noisy. Sen. Feinstein wrote to the postmaster general and asked him to consider “alternative sites” for the project, mentioning the El Toro project being developed by Lennar. She remained careful, however, not to disclose the role her husband’s company played in its $1.4 billion development.

Temporarily delayed by the crash of Lehman Brothers, development of the former El Toro base is now complete. Blum’s CBRE, a company reportedly worth $6.8 billion, claims on its website to have provided both consulting and brokerage services in the project. CBRE also brokered the sale of the less spectacularly priced $7.5 million plot of land in Aliso Viejo.

But the mysterious connections linking wife Feinstein’s politicking with husband Blum’s profiteering don’t stop there. Through her aides, Senator Feinstein allegedly used her office to get inside information for the benefit of her husband’s company. Between the summers of 2011 and 2012, Feinstein’s former chief council and then current aide, David Hantman, exchanged emails with U.S. Postal Service staff asking them about the federal properties slated to be sold.

Hantman specifically asked about properties subject to historic designations and environmental protection reviews under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) – conditions that would potentially prevent their sale. On May 24, 2012, when Hantman asked USPS staffer Mary Ann Simpson about postal properties scheduled for sale on the National Register of Historic Places, he included as a tagline: “My boss is just curious”.

Coincidentally, while Hantman was sending those emails on behalf of Senator Feinstein, CBRE was conducting historic place and environmental protection reviews for the very same postal properties. In an email sent in February of that year, Hantman asked Simpson if she wanted any input on amendment ideas for a postal reform bill. Seen in retrospect, the correspondence raises questions that no one has answered about the language that may have been inserted into the postal reform bill to make it easier for CBRE to skirt historic preservation and NEPA laws in its later sales of postal property.

Creating an Artificial Panic

The robbery of the U.S. Postal Service began with the passage of the Postal Reform and Enhancement Act (PREA) in 2006, which passed the 109th Congress by a voice vote in the House and Senate. The bill required the USPS to pay the healthcare benefits of all employees through 2056, including benefits for employees who have yet to be born. The timing of the bill was important: PREA was introduced, and passed, in the lame duck congressional session just after a Republican majority was ousted in the populist and anti-war electoral wave of 2006. It was the last, defiant stand by politicians whose constituents in many cases had just unelected them from office.

PREA was also the beginning of the Post Office’s spiral into financial catastrophe. Since the bill was enacted, the USPS has had to make$5.5 billion in annual payments to retiree healthcare plans. (Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont argues that the USPS should be allowed to immediately collect $13 billion that has already been overpaid into those accounts.) Eventually the Post Office’s fiscal situation became so dire that the USPS was effectively forced into negotiating a contract with none other than CB Richard Ellis, which was put exclusively in charge of selling off 52 postal properties located in prime real estate zones throughout the country.

The payoff: CBRE has been selling those properties to its own business partners at extremely discounted prices, representing both the buyer and the seller in the transactions while cheating the USPS out of millions.

Perhaps most remarkably, the man in charge of the USPS’s facilities management division, Tom Samra, who is worth a reported $98 million, ignored an open conflict of interest as he signed his name on fraudulent invoices that kept the gravy train rolling.

Ineffective Contract Oversight

But not everyone has remained silent in the face of this national scam. Last June, the Post Office Inspector General’s office wrote a scathing report highlighting clear conflicts of interest and fraud in CBRE’s handling of the USPS real estate sales. The Inspector General’s office found that CBRE had no maximum contract amount set by the USPS, leading to over-payments to CBRE stretching the Post Office’s already tight budget.

On page 4 of the report, the Inspector General revealed that 227 invoices submitted by CBRE, valued at $1.7 million, were approved by someone not designated as an official contract officer. The original $2 million budget for CBRE’s contract swelled to almost three times that, since no maximum contract amount had been set.

Moreover, the contract was shown to include problematic invoices submitted by CBRE, which often included insufficient details of the transaction yet still got approved by Tom Samra’s staff. As Peter Byrne explains in Going Postal, one such deal happened at the height of the development of downtown Boston’s Seaport district – a prime real estate zone known as the Channel Center where a bevy of upscale apartments, office buildings and parks were slated to be built, right next to the financial district.

The buyers of the zone were CBRE’s own business partners, Commonwealth Ventures, LLC. The parking lot property was sold for several million dollars less than it was assessed to be worth. CBRE’s invoice, which Samra signed off on, contained false information, no actual address of the property, and a question mark in the space listing the property’s value. And although the USPS’s contract stipulated that there would be no flat fees, CBRE still demanded a flat fee of $377,500 for the sale, which the USPS paid.

Basic ethics in the real estate industry stipulate that a company must sell its clients’ properties at or above fair market value. Yet CBRE quietly sold 52 postal facilities valued at $232 million for a total of $166 million in the first two years of its contract. Excluding nine properties that sold at above market value, CBRE undersold the USPS’s real estate portfolio by $79 million in deals that enriched the corporation, its numerous business partners – and above all, CBRE’s billionaire Chairman Richard Blum and his senatorial wife.

Accountability

In June of last year, Factcheck.org called Senator Feinstein’s press secretary to ask if the senator stood to benefit from her husband’s business. The aide roundly denied the allegation, saying that Sen. Feinstein’s wealth remained completely separate from her husband’s – despite the fact that Feinstein shares in her husband’s wealth through the mere fact of their marriage.

Feinstein’s press secretary also told Factcheck.org that the senator’s assets are held in a blind trust. But public records reveal that Feinstein and the 77-year-old Blum co-own multiple homes in San Francisco and Washington, DC, and share approximately $100 million in net worth between them. In fact, according to the Washington Post, Feinstein herself was worth $69 million as of 2010, and had increased her wealth by 12 percent over six years.

In what appears to be at least a serious conflict of interest, if not more, these facts give rise to whether there should be a formal, thorough investigation into the relationships between Tom Samra of the U.S. Postal Service, Richard Blum of CBRE, and his wife, Senator Dianne Feinstein. The real question is whether Congress has the will to go after one of its own.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments