On a recent lunch hour in the bustling cafeteria at St. Anthony’s Church in the Tenderloin, where free meals are served daily to hundreds of cashless San Franciscans, Jelua Montero nourished herself with a tray of hot chicken posole, bread and vegetables.

The Nicaragua-born 47-year-old, with wavy black hair and a wiry but sturdy build, gets lunch here often — especially since she lost her minimum wage job in January working as a security guard downtown at the Westfield Mall. But even before that, working seven days a week with no overtime pay, Montero said she was barely making ends meet, even with an array of free services offered to homeless people.

“I was able to survive in a shelter, by eating in a shelter,” Montero said. “I was working and working and still couldn’t get a room, couldn’t get into an SRO” — a single-room occupancy hotel. Montero said she has been waiting a long time for subsidized housing, but her number hasn’t come up yet.

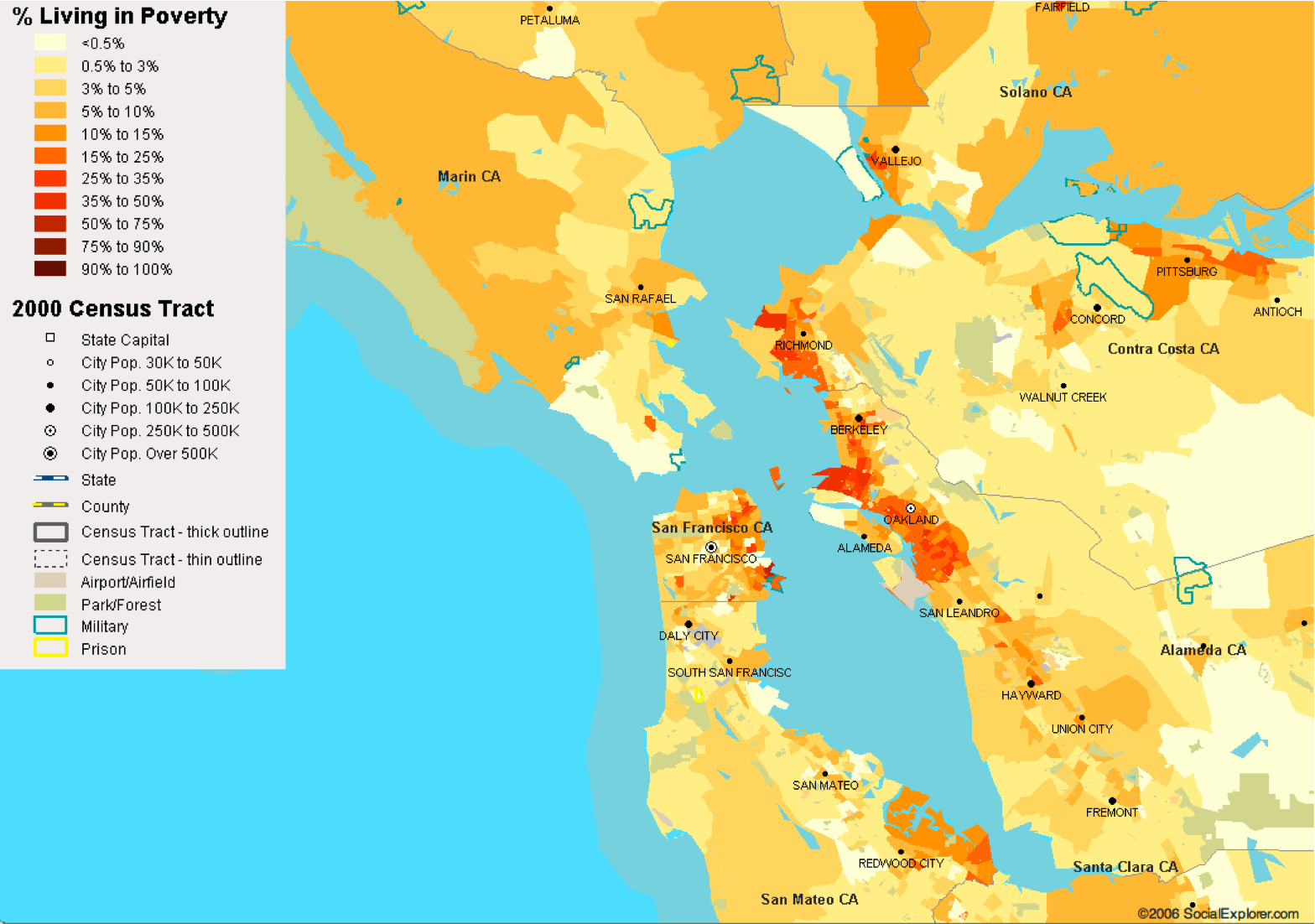

Through the 1990s, Montero shared a two-bedroom, rent-controlled apartment near San Francisco General Hospital for $550 a month — but since losing her space in 2003, she has struggled to find a new place to live, despite being regularly employed as a guard. With rents soaring and housing limited, Montero said, “I don’t think you can survive in this city on the minimum wage. The rents are too high — the landlords are getting all the money.”

As President Obama’s minimum wage hike proposal renews a national debate over costs and benefits, many low-wage workers in San Francisco say they can hardly get by even on the nation’s highest minimum wage of $10.55, which is nearly $3 an hour higher than the federal rate.

“If it weren’t for my subsidized housing, I’d be out of luck,” said Mark Anthony, 56, who needs extra benefits from the city and from charities, even though he makes about $12 an hour working banquets part time for Select Staffing.

“I’ve been pinching pennies, it’s very challenging,” Anthony said over his chicken posole lunch at St. Anthony’s, sitting family style with other hungry adults and families. “I couldn’t hardly afford to feed myself if it weren’t for this place.”

A few tables over, 49-year-old Marcus Taplin said he was able to survive in the city, thanks only to a range of services supporting his minimum-wage janitorial job in the Tenderloin. Without the help, he said, “I don’t think I’d be in the city at all.”

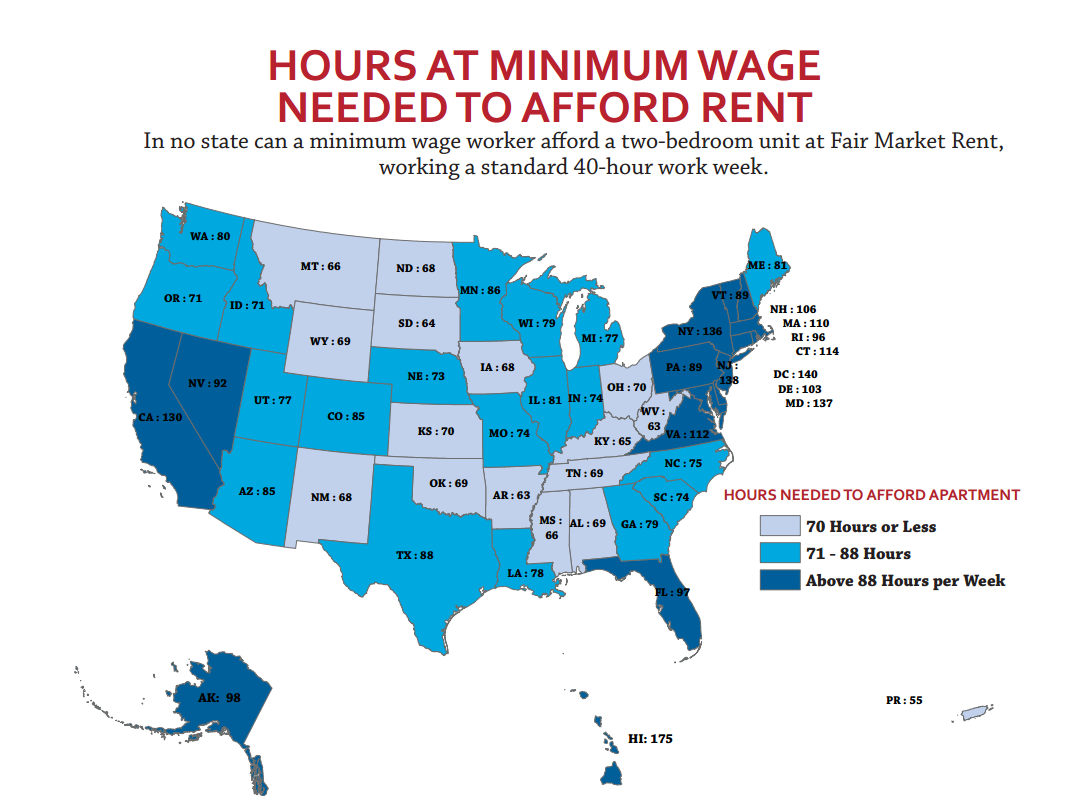

As rents have soared above $1,500 for a typical studio apartment and more than $2,000 for a one-bedroom, low-income workers say San Francisco’s minimum wage isn’t enough to keep up. A full-time minimum-wage job in the city brings in $21,100 before taxes. Yet a below-market-rate rent of $1,000 a month amounts to $12,000 a year — more than half of that income.

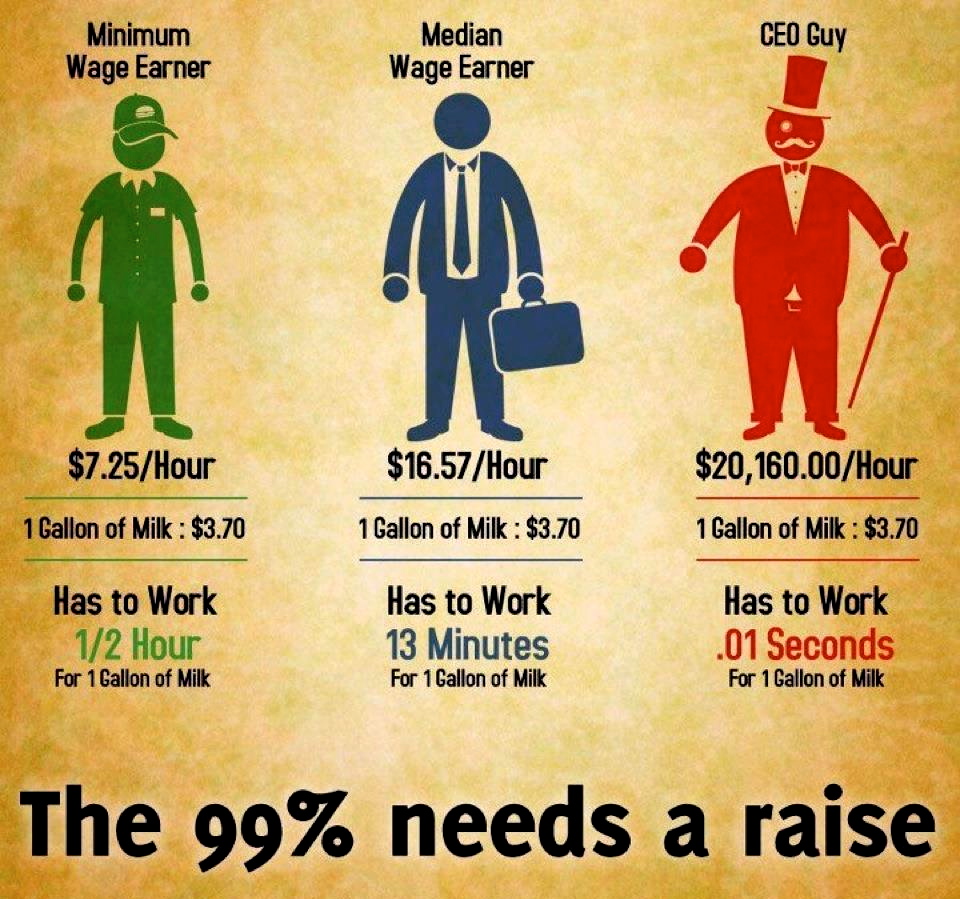

Nationally, the minimum wage has not even come close to keeping pace with inflation. According to data analysis by the Economic Policy Institute using 2011 dollars, the federal minimum wage of $7.25 that year was worth a full dollar per hour less than the minimum in 1967.

“A lot of people are ‘making it’ by going without,” said Colleen Rivecca, advocacy coordinator for St. Anthony’s, “by skipping meals, not going to the doctor and walking instead of taking the bus.”

In 2011, St. Anthony’s surveyed its dining room visitors and found that 19 percent had “no income whatsoever” and 29 percent reported income of less than $100 a month. Nearly all, 91 percent, earned less than $1,000 per month.

When asked if it’s possible to survive in San Francisco on the minimum wage, Jim Lazarus, vice president of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, said he believed it could be done: “Like it or not,” Lazarus said, “it’s called roommates and multiple-income households. My wife and I have both worked for years, and our kids work and live with roommates.”

Originally published by San Francisco Public Press.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments