Seven US states have passed laws that ratchet up the penalties for activists protesting. - Susie Cagle/The Guardian

From the Standing Rock camps in North Dakota to tree-sits in Texas, activists have attempted to stop pipeline construction with massive shows of civil disobedience. Now they could be forced to change those tactics, or face heavy penalties under a wave of new anti-protest laws that civil liberties advocates say violate the first amendment.

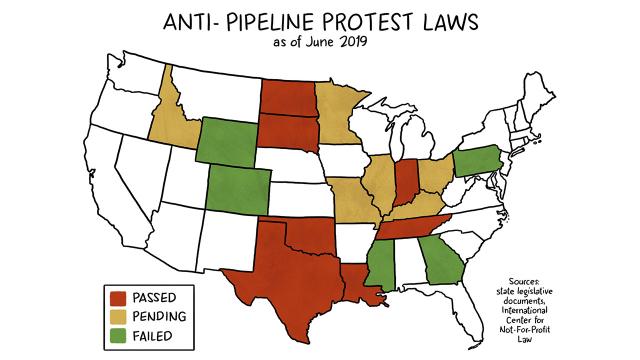

Conservative lawmakers have put forward laws criminalizing protests that disrupt the construction and operation of pipelines in at least 18 states since 2017.

-

Seven states have passed laws that ratchet up the penalties for activists protesting or even planning protests of oil and gas pipelines and other “critical infrastructure”

-

At least six more states are considering such laws

-

In each case, misdemeanors are elevated to felonies, and criminal and civil punishments are escalated drastically

-

The ACLU and the Center for Constitutional Rights have mounted challenges against such laws in Louisiana and South Dakota.

“This is a trend that shows no sign of slowing, let alone stopping,” said Elly Page, who has been tracking anti-protest legislation for more than two years as a legal adviser for the International Center for Non-Profit Law.

The laws purport to only criminalize violence and property damage in service of pipeline safety, but critics say their greater intent appears to be to deter nonviolent civil disobedience by framing it as potentially violent in itself.

The bills have mostly found fertile legislative ground in places where gas and oil companies already wield significant political and economic power and where anti-fossil fuel protests have been especially successful. But watchdogs say there’s every reason to believe more of these types of laws will be passed, and that they will chill activism otherwise protected by the first amendment.

“This is a miscasting of protesters as economic terrorists and saboteurs when in fact they’re going out and having their voices heard about why these pipelines are problematic for their communities and the environment,” said Vera Eidelman, a staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union. “Even if folks haven’t been charged, the fact that these laws are on the books can seriously chill people and make them fearful of getting their voices out,” she added.

A wave picking up speed

Oklahoma was the first to pass pipeline-protecting legislation in 2017, with a pair of bills that ostensibly protected critical infrastructure from trespass and damage. By the end of the year, the American Legislative Exchange Council, a non-profit coalition of conservative politicians and industry representatives, had developed model Critical Infrastructure Protection legislation based on Oklahoma’s laws. Energy industry groups immediately sent a letter to legislators urging them to adopt the bill in their states.

That effort has proven fruitful.

Louisiana passed a version into law in 2018, and the legislative wave picked up speed in 2019. Laws that would increase criminal and civil penalties for protesting against gas and oil pipelines specifically and “critical infrastructure” more broadly have passed this year in Tennessee, Indiana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Texas, and are currently pending in Idaho, Minnesota, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio and Kentucky. In each case, the laws provide for more extreme criminal charges and civil penalties for trespass and vandalism against pipelines.

Industry representatives insist these harsh penalties are necessary for pipeline security. “The intent of the critical infrastructure bill signed into law last year is to protect the safety of Louisiana’s people, environment and infrastructure,” the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association president and general counsel, Tyler Gray, said in a statement in May. “It is straightforward in its scope and application and does not infringe on an individual’s constitutional rights.”

When the Texas law goes into effect on 1 September, it will make “impairing or interrupting” pipeline construction a felony, punishable by up to two years in jail and a $10,000 fine. If an activist is alleged to have “intent to damage or destroy” a pipeline facility, they could face a third-degree felony on par with attempted murder, and up to 10 years in prison. And any organization found to be similarly culpable could face a $500,000 fine.

“It’ll be more difficult to give underrepresented communities a voice now because of this,” said Frankie Orona, executive director of Society of Native Nations, which vigorously opposed the bill.

Similar measures seem to have support at the federal level. The Trump administration, stacked with former fossil fuel industry lobbyists, attorneys and executives, has come out with its own proposals to protect fossil fuel infrastructure.

A June proposal of the Department of Transportation for “Protecting our Infrastructure of Pipelines and Enhancing Safety Act” included a provision to expressly strengthen criminal penalties for “impeding, disrupting, or inhibiting the operation of a pipeline facility”. The head of the Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration was formerly a vice-president of one of the country’s largest coal transporters.

The department’s proposal used “some of the same language and ideas in terms of covering peaceful protest activity”, said Elly Page.

Shutting down activist resources

Although the anti-protest laws are highly specific in explicitly or implicitly targeting oil and gas infrastructure, they’re highly vague when it comes to defining what behaviour is prohibited. The laws define “critical infrastructure” as a range of private and public energy facilities, including those that are under construction, but what constitutes imposition, disruption, inhibition or conspiracy is left up to a court’s interpretation, as is what constitutes “intent” to damage property.

Yet if preserving infrastructure safety and fossil fuel company profits are the goal, there are already a variety of legal tools available to law enforcement. Trespassing and damaging private property are already crimes in every state. “States already criminalize most if not all of the conduct that’s covered by these laws,” said Page. “It seems to be part of a larger effort to stifle certain political speech and environmental groups.”

The laws appear designed not just to deter individuals from protesting, but also to cut off material support from organizations by levying steep fines on organizations alleged to conspire with activists. South Dakota’s governor, Kristi Noem, admitted as much about the law in her state in March and said that the law was intended in part to “shut down” activist resources – she named George Soros as the top “national offender”.

By a particularly cruel twist in South Dakota’s law, which flew through the state legislature in just one week, those fines could actually be used toward the construction of the pipelines activists protest against.

‘An industry-created issue’

When off-duty police working as private pipeline security pulled Cindy Spoon off her canoe in southern Louisiana last August and handcuffed her, she didn’t yet know she would be one of the first activists in the country charged with a felony under this new spate of legislation.

Spoon was working with the L’eau Est La Vie camp protesting against the construction of the 163-mile Bayou Bridge pipeline, which carries crude oil through the vast wetlands of the Atchafalaya Basin. She was boating in navigable, public waters – the equivalent of being in the public road. But she was charged with felony trespassing, a little over a week after Louisiana’s protest law went into effect.

If the district attorney pursues her case, Spoon could face up to five years in prison. Sixteen activists are currently facing felony charges under the Louisiana law for peaceful protest either in public waterways or on private land where they had the owner’s permission to be.

Spoon remains determined to continue her work. “The risk involved to me personally is far outweighed by inaction,” she said.

Spoon’s pro bono attorney Bill Quigley and the Center for Constitutional Rights have filed a federal suit challenging the law in Louisiana.

“This is not a problem that any private citizen has ever filed a complaint about. This is a total industry-created issue,” said Quigley, a law attorney at Loyola University New Orleans. “They are essentially passing these laws to give themselves enhanced protection.” When he attended the state senate comment session for the Louisiana law in 2018, Quigley said, he was joined by nearly two dozen fossil fuel industry representatives. “There were no private citizens.”

In South Dakota, the ACLU has filed a suit challenging the law in South Dakota.

Dallas Goldtooth, who is Dakota and Diné, is a named plaintiff in that lawsuit. Goldtooth, a campaign organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network, has been protesting pipelines since 2013, and using his substantial social media following to boost activist efforts – speech that could now be considered “riot-boosting” in South Dakota.

Goldtooth is ready to take that chance. But he worries that even if communities on the frontlines whose lands are being carved up by pipeline construction are willing to take on the increased risk of protest, others won’t. “The fear is that our allies are going to be intimidated and too afraid to come out and stand in solidarity,” said Goldtooth. And in sparsely populated rural America, numbers are everything.

While some communities may successfully push pipeline construction to the next, less-fortunate community over, these projects are rarely if ever shelved. There are few places in America that remain untouched by an oil or gas route. Pipelines touch every state in the US except Hawaii.

“They’re just picking the low-hanging fruit right now, the places where oil and gas have outsized influence. But oil and gas pipelines are everywhere. It’s not just Louisiana and Oklahoma and South Dakota,” said Quigley.

“I guarantee a law like this is coming to your state.”

Originally published on The Guardian