A proposed $5 billion pipeline that would deliver natural gas to the Southeast is finding pockets of opposition along its planned path in West Virginia and Virginia, where it would carve through two national forests.

The 550-mile Atlantic Coast Pipeline is also seeing resistance in remote high-elevation sections of Virginia amid concerns it would traverse an environmentally sensitive landscape. Some landowners also object to plans for the pipeline to dissect their property.

Some landowners, such as Andrew Gantt, are pushing back. He has refused to let surveyors onto hundreds of acres in Nelson County, midway between Charlottesville and Lynchburg, that are devoted to loblolly pines and hardwoods such as maple and oak. The ancestral land dates to the first European settlers.

“To have a natural gas pipeline charge through this land that we have worked so hard to keep for so long is a travesty,” Gantt, 78, said.

If construction crews come on his property, he said, “Then I’ll lie down under their bulldozer. I’m serious.”

The pipeline has plenty of supporters, for sure, including Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe. The Democrat has called the project a “game changer” that will enrich the state’s economy by attracting new businesses with the promise of abundant and relatively cheap energy supplies.

McAuliffe’s counterpart in West Virginia, Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin, has sounded a similar sentiment. The energy project “has the potential to create good-paying jobs for our hard-working men and women,” he said in a statement.

Officials in a number of localities along the planned route also have embraced the project, which would deliver natural gas to Virginia and North Carolina.

A study commissioned by Dominion concludes the pipeline’s construction could have a total economic impact of $2.7 billion in Virginia, North Carolina and West Virginia.

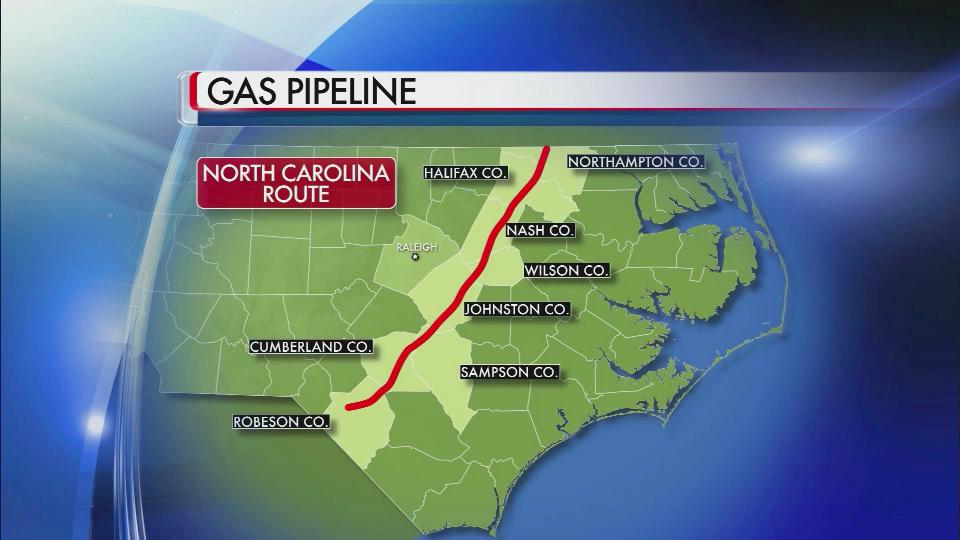

The pipeline is being proposed by Dominion Resources, Duke Energy and other partners to deliver natural gas from Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. It would begin in Harrison County, West Virginia, and stretch through Virginia and North Carolina to Robeson County, near the South Carolina border.

The pipeline, most of which would be buried three to five feet deep, would deliver 1.5 billion cubic feet a day of natural gas a day from drilling in the Marcellus and Utica shale deposits. Those account for more than one-fourth of the nation’s natural gas.

Much of the opposition is centered in rugged mountainous terrain along the West Virginia and Virginia state line. Citing grave concerns about the pipeline’s impact on the region, 22 conservation and environmental groups in both states have teamed up to monitor and, in some instances, battle the energy project.

Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance members are fearful the path of the project will trample on some of the most ecologically sensitive areas in the eastern United States. Some, for instance, fear a loss of habitat for the Indiana bat and the cow knob salamander.

The Southern Environmental Law Center is a member of the coalition, and its primary concern is the pipeline’s path through two national forests. It would carve a 16.9-mile route on federal land through the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia and 12.9 miles through the George Washington National Forest, also on federal land.

The pipeline’s route through the GW National Forest would go through “the most intact forestland in the entire region” and undermine the economies of localities that rely on outdoor recreation and the national forest to bolster their economies, said Greg Buppert, a senior attorney with the SELC.

“We’ve worked for years to help protect public lands in the George Washington National Forest from other industrial activity,” Buppert said. “The pipeline is essentially a major industrial activity with a big linear footprint through rugged, intact habitat.”

Buppert said a major concern is that sediment and other pollution from the pipeline’s construction would foul streams that contain native trout and the headwaters of streams that provide water to downstream communities.

Chet Wade, vice president for corporate communications for Dominion, said national forests already allow commercial activities such as timbering. He said the utility has worked with the U.S. Forest Service to adjust the pipeline’s path through the national forests.

“Obviously, you want to be very respectful of the forest and protect the most sensitive areas,” Wade said. The Monongahela National Forest, he noted, already is home to a natural gas pipeline and a gas storage field.

For opponents in two Virginia counties — Highlands and Augusta — the concern is the karst topography that runs along the western spine of Virginia. That landscape of limestone and other bedrocks is particularly porous, fragile and susceptible to sinkholes. The region is a popular destination for cave explorers.

The fear is construction of the pipeline or a breach in it could cause widespread contamination to the water table beneath, polluting waters that serve local communities.

Wade provided a map showing a number of pipelines carrying crude and natural gas through similar terrains through Virginia, West Virginia and elsewhere. All were “successfully built in karst topography,” he wrote in an email.

The pipeline requires approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. It also will be reviewed by various state environmental agencies. The energy companies expect to receive approval by mid-2016 and to start operating the pipeline in 2018.

Opponents say they will press federal regulators to alter the pipeline’s path.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments