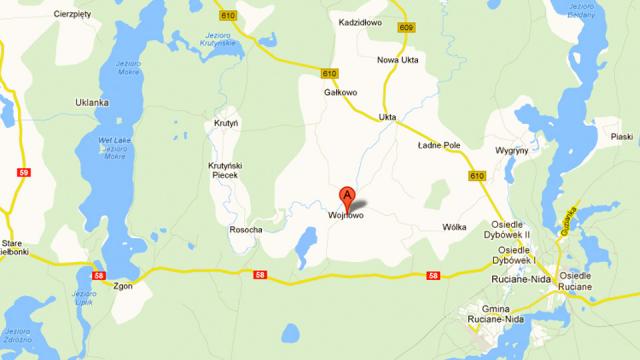

Teresa Mikołajczak is a retiree living in Wojnowo in the west of Poland. The next town is six miles away. To visit the doctor she needs to travel 10 miles. Teresa has no car. She used to make the trips by bus but these days that's an impossibility.

“Tomorrow I must go to the dentist and now I'm struggling to figure out how to get there and how to get back,” she said, because there are no buses in Wojnowo anymore.

Poland was widely praised as the European state least touched by the financial crisis in 2008. Its economy grew even when all of its neighbors, including Germany, were in recession. With the wave of funds provided by the European Union in recent years, the country managed to connect its major cities by freeway and improve its infrastructure with shiny new sports fields.

At the same time, Poland climbed in education to 14th worldwide, according to the most recent PISA ranking by the Organization for Economic Cooperation, putting it ahead of the U.S., Sweden, France, Germany and the U.K.

But these types of development are only one side of the coin, as Teresa's experience shows. In Poland's version of modernization, like in many other places, the biggest advantages have gone to cities while the countryside has become ever more marginalized. This might be a positive trend -- if Poland's rural population did not still include 40% of its inhabitants.

And in the case of losing public transportation, things here couldn't appear more backward.

“At the beginning of the year we waited for a bus with some of my neighbors. A few people were going to work, others had various errands," Teresa explained. "The bus had a relatively huge delay, so I decided to call the company to find out what was happening. A man told me that the connection had been suspended. It was such a shock for us that I started to cry. They left us without any bus connection.”

A similar shock awaited people far beyond Wojnowo. PKS, the company responsible for commuting people by bus in the region, suspended 88 connections at the beginning of 2013. The simple reason, according to a PKS spokesperson: “We couldn't afford to maintain these connections."

And that same economic excuse has, more recently, also justified the closure of commuter rail lines by the Polish National Trains company.

On February 18, the national trains company, PKP, published the list of rail lines that will close over the course of the year. In total, some 2,000 kilometers of track will go out of use. Train stations on the closed lines will be sold. According to the list, PKP will lose 800 train stations.

This is part of an ongoing, decades-long process. Since the transition from communism to democracy that began in 1989, PKP has closed around 5,000 kilometers of rails, which connected predominantly small cities and communities that were forced to bear the brunt of the impact.

Granted, the quality of public transport in Poland has never been very good; even in the past, the schedules of buses and trains weren't frequent enough. When Poland joined the E.U. in 2004 and customs agents on the border with Germany disappeared, used and cheap cars from Germany became widely available.

Since then, the number of passengers taking public transportation has decreased while the number of private cars on the roads has risen dramatically - a trend that further justifies the government's prioritizing investments for roads while neglecting the railway system.

The negative economic impacts on average people, again, have been felt strongest in rural areas. For one, it is far more expensive to travel by car then by public transport, forcing families with modest means to make hard new decisions about how to spend their money. In the case of Teresa, and so many others, owning a car is not even a financial option.

“I will have to ask my neighbors, or beg for a ride from random people. For my whole life I was independent, and now I am like an object," she said. "In some sense it is humiliating.”

Poland's income gap is growing steadily. Country schools and libraries are struggling to remain open. So are post offices and police stations. Now, as the country's "modernization" comes at the cost of a further tax on its poorest citizens, thousands if not millions of people risk being literally, physically, left behind.

The fact that Teresa and so many others like her will have to beg for a ride, or risk being cut off from the rest of the world, is a significant step for Poland.

And make no mistake: the step is backward, not forward.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments