Earlier this spring, I was part of an international delegation of election observers that traveled to the community of Nueva Trinidad in northern El Salvador to observe an act of direct democracy where the people would vote “Yes” or “No” on whether to allow metallic mining in their community. This type of popular referendum is crucial at a time when decisions that impact people's lives and communities' health are increasingly controlled by corporate boardrooms – and courtrooms – that serve only profit.

The U.S. Congress recently debated legislation to Fast Track an expansive free trade deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which would impact a large swath of the global economy. If approved, Fast Track means that the sweeping trade deal, which has been negotiated in secrecy over the last six years, could be approved without amendments or public input.

The TPP would outsource millions of American jobs, strip consumer protections and accelerate climate change through the expansion of fossil fuel development. One of the most frightening provisions of the TPP would expand transnational corporations' ability to sue governments for any regulatory protections that might hinder access to corporate profit – a point that brings us back to El Salvador, where the Canadian mining corporation Pacific Rim, now a subsidiary of OceanaGold, is using provisions under existing free trade agreements to sue the government of El Salvador for $300 million, claiming it lost profits due to its revoked permit to mine.

With numerous cases like this pending in international investor courts, and other secret trade deals hanging in the balance, it raises the question: Who should be making mining decisions for these communities? Seeking insight to this question and others, our international delegation of observers traveling to El Salvador included representatives from mining-impacted communities in Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, as well as observers from the U.S., Canada and England. The week-long journey took us through the past, present and future realities of metallic mining in El Salvador.

Tragic Legacy of Metallic Mining in El Salvador

Stepping off the bus in the rural community of San Sabastian, I was first struck by the intense, dry heat under the midday Salvadoran sun. Then I noticed something deeply unsettling about the water in the river below us. It was orange.

Our delegation gathered on the river banks under a scraggly tree to hear local resident Gustov Blanco talk about the history of mining in his community. The first gold mine was opened in the mountains near the community in 1906, and from that time until its closure in the 1980s, transnational corporations have extracted a fortune from over nine tons of gold.

When the Wisconsin-based company Commerce Group finally had its permit revoked by the Salvadoran government, it abandoned the mines and dumped piles of contaminated rock waste on a hillside near the river. The toxic chemicals from the mining waste leached directly into the river that runs through the heart of the community, caking the riverbanks in a yellowish-white contamination.

Official water testing reveals an alarming level of cyanide that’s nine times the permissible national level for potable water. Many of the rocks near the river are visibly green with cyanide contamination. Kidney failure and rare diseases are common in the small community, including five cases of a rare disease that normally only occurs in one in 100,000 people.

"With all the gold they extracted, they could have at least left us with some kind of potable water system," said Mr. Blanco. "The company simply left... leaving behind only contaminated water and lands. They didn't leave any benefit for us, just illnesses."

This toxic legacy of poverty and pollution represents an inescapable and mutually-reinforcing cycle that forces residents to use the poisoned water to survive, or spend what little money they have to bring in expensive water from elsewhere. Large tanks of potable water cost upwards of $20, an almost unattainable amount for those who survive mainly on subsistence farming. Even when the mines were open, locals would earn a meager $6 a day laboring in the depths of the mines. Now they don’t even have those jobs.

After Commerce Group had its permit revoked and abandoned the mine, it added insult to injury by using provisions under the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) to sue El Salvador in the World Bank’s investor court, the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The case was thrown out on a technicality, but still pending is the previously mentioned $300 million case in the ICSID court against the government of El Salvador.

The story of the San Sabastian mine is an empirical example of how free trade agreements like CAFTA and the TPP pave the way for destructive transnational corporate extractivism by establishing legal protections for them to pollute with impunity, and then allowing them to demand a big pay out afterwards.

Assassinations of Anti-Mining Community Activists

Prayers and funeral songs from a nearby church hung heavy in the hot thick air as we gathered under the metal roof of a school in the village of La Maraña. The tone was somber as our hosts explained that their full group wasn’t able to attend our meeting because there had been a sudden death in the community.

We sat with members of the community's anti-mining group, La Maraña Environmental Association (MEA), in a circle of plastic chairs that felt as if they might melt under the metal roof. The group’s Vice President, Alejandro Guevara, removed his broad-brimmed hat as he told us the long history of his community’s resistance to the mining corporation Pacific Rim. The Canadian-based company currently holds numerous untapped mining concessions in their department of Cabañas.

When Pacific Rim arrived in 2004, community members began working with them to collect samples and conduct initial testing in the area. At the time, the only thing residents knew about mining came from Pacific Rim’s promises of jobs and a better life for the impoverished community. But as the company’s exploration became more invasive, people started to ask questions and organize opposition. Pacific Rim’s response was to launch a PR campaign, make symbolic donations to local events, and put the mayor on their payroll.

The results deeply divided the community as people began to speak out, and the repression tactics escalated with increasing threats of violence against members of the MEA. After increasingly tense resistance that included some confrontations between community members and company employees, Pacific Rim was prepared to negotiate. The firm's president even flew in from Canada with the hope of brokering a deal to win over local residents. But community leaders held firm and responded with a resounding “no.”

Then the violence began. One evening, a spray of 9mm bullets aimed at Mr. Guevara ripped through the back of his house. He survived the assassination attempt, saying his assailant only missed because “God covered the eyes of the shooter.” Another group member named Romero survived a shotgun blast, and the MEA president, a father of six, shared the story of a similar attempt on his life.

During our visit, he held up newspaper clippings about leaders from other nearby communities who hadn’t been so lucky. In 2009, three anti-mining activists from Cabañas – Marcelo Rivera, Ramiro Rivera and Dora Recinos Sorto, who was eight months pregnant – where murdered. Authorities dismissed the shootings as gang-related even though they clearly targeted only anti-mining leaders and didn’t match the established patterns of gang activity.

Despite the threats to their lives, members of MEA still continue to organize to defend their community. Through tears, Mr. Guevara explained that they may be killed in this struggle – but that they need to keep fighting or mining will mean the death of the entire community. “We’ll be here until God takes us away,” he said defiantly.

The case in La Maraña is endemic of an alarming trend of escalating violence and assassinations against environmental activists across Latin America in recent years, as documented by a new report from Global Witness. The increasing incursion of corporate polluters under the auspices of free trade is being met with a growing grassroots resistance of communities, many of them indigenous, from across the continent.

The greatest hope for the future of the anti-mining movement in El Salvador lies with existing, well-organized communities that can prevent companies from getting an initial foothold and dividing them with violent repression.

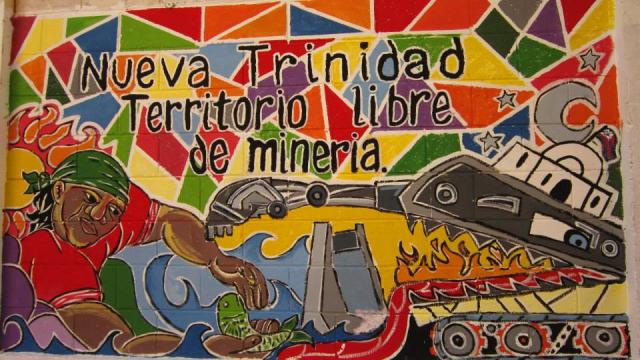

Voting to Ban Mining in Nueva Trinidad

Before we could even get off the bus at our last stop in the village of Carasque, community members climbed aboard and where joyously embracing the members of our delegation from Bangor, Maine. The roots of this reunion date back to El Salvador’s bloody civil war between 1980 and 1992 that killed 75,000 people. During the war, communities from both countries established a solidarity “sister” relationship that helped protect Carasque from government death squads. Today, the organization US-El Salvador Sister Cities, which helped organize the delegation, continues to foster the relationship of solidarity and facilitates regular monthly conversations between Carasque and Bangor.

Carasque is located in the northern department of Chaletenango, which was one of the hardest hit regions during the war. Many people in the area, including from nearby Nueva Trinidad, returned from refugee camps in Honduras late in the war to find their communities had been reduced to rubble by the U.S.-backed Salvadoran military bombings. Over the objections of the government, they began to repopulate their homes and rebuild their lives.

Today, mining threatens everything they’ve painstakingly rebuilt over the years – which is why they're determined to defend against it at all costs. The community has used many tactics to stop mining, including public education, demonstrations, and direct action in the form of road blockades and removing survey tape. One creative tactic even involved the placement of beehives on unattended mining equipment.

Then, after over a decade of creative resistance, people were ready for something new. An innovative strategy emerged to build grassroots power while challenging the legal legitimacy of mining companies. Communities have begun to use a community consultation process that has never before been used in El Salvador’s history. Many national and regional organizations have united to advance this new strategy, including the National Roundtable Against Metallic Mining in El Salvador (La MESA), the Association for the Development of El Salvador (CRIPDES), and the Association of Communities for the Development of Chalatenango (CCR).

The consultation process is initiated when 40% of a community population formally requests a meeting about an important issue facing the community. Then the municipal government holds a popular vote in which community members get to vote “Yes” or “No.” The vote in Nueva Trinidad marked the third community in the country to ever hold a consultation following the leadership of others like San Jose Las Flores and San Isidro Labrador, which both voted in overwhelming majorities to ban mining.

Finally, on March 29, after months of organizing and preparation, the day of the vote arrived. Our group of observers were dispatched to each polling location to watch and verify the validity of the voting process. Throughout the day, voters young and old turned out at the polls. The atmosphere was festive as neighbors gathered to share stories and food as they cast their votes.

After the polls closed, we gathered in the town center of Neuva Trinidad to hear the final results: an astonishing 99.5% of the community had voted to ban mining in the territory. A jubilant crowd gathered to hear speeches from the mayor and other community leaders as vendors sold snacks and pupusas. Now, in the wake of Nueva Trinidad's victory, other communities across the country are already lining up to be the next to ban mining in their territory.

This is a significant trend, since the $300 million lawsuit from Oceana Gold is expected to be decided in the international investor court sometime this summer, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership still hangs in the balance.

Emerging from a checkered legacy of war, poverty and pollution, communities like Nueva Trinidad are writing a new history in which they are the ones empowered to decide the future of their communities. The U.S. can learn a lot from the struggles and strategies of its "sister cities" in El Salvador. And from Maine to Texas, communities are beginning to grow this grassroots power. As corporate polluters act in lock step with the politicians whom they fund, town and cities across the continent are defying the odds and declaring themselves free from dangerous extractivist projects.

In the U.S., for communities to succeed against transnational corporations, they must continue to build relationships of solidarity and learn from others' innovative strategies organizing at the intersections of free trade, environmental injustice and immigration. Regardless of which hemisphere and which form of corporate abuse, community organizing and direct democracy appear to be the best, and universal, antidote.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments