The U.S. court of appeals has ruled that the bulk collection of telephone metadata is unlawful, in a landmark decision that clears the way for a full legal challenge against the National Security Agency.

A panel of three federal judges http://www.irmina.co.uk/ for the second circuit overturned an earlier ruling that the controversial surveillance practice first revealed to the U.S. public by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013 could not be subject to judicial review.

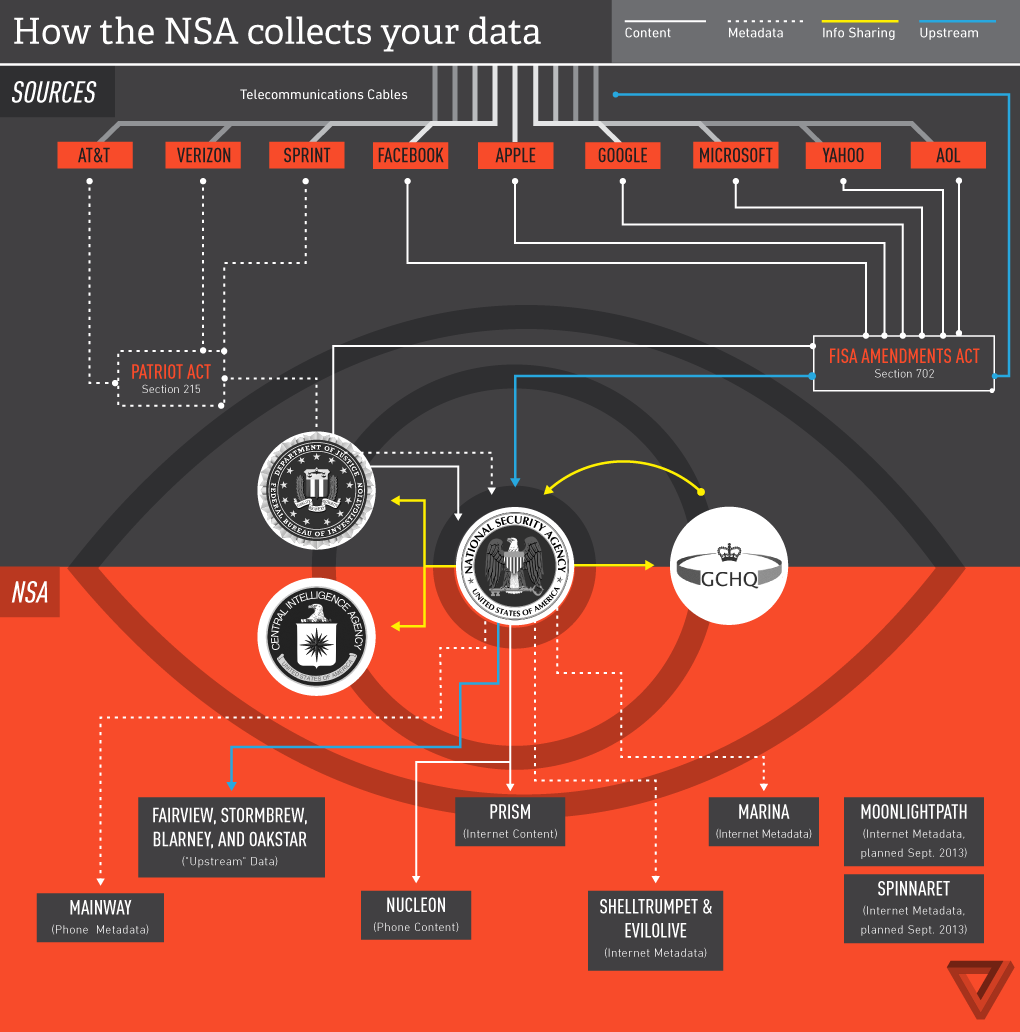

But the judges also waded into the charged and ongoing debate over the reauthorization of a key Patriot Act provision currently before U.S. legislators. That provision, which the appeals court ruled the NSA program surpassed, will expire on June 1 amid gridlock in Washington on what to do about it.

The judges opted not to end the domestic ralph lauren uk stores bulk collection while Congress decides its fate, calling judicial inaction “a lesser intrusion” on privacy than at the time the case was initially argued.

“In light of the asserted national security interests at stake, we deem it prudent to pause to allow an opportunity for debate in Congress that may (or may not) profoundly alter the legal landscape,” the judges ruled.

But they also sent a tacit warning to Senator Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader who is pushing to re-authorize the provision, known as Section 215, without modification: “There will be time then to address appellants’ constitutional issues.”

“We hold that the text of section 215 cannot bear the weight the government asks us to assign to it, and that it does not authorize the telephone metadata program,” concluded their judgement.

“Such a monumental shift in our approach to combating terrorism requires a clearer signal from Congress than a recycling of oft‐used language long held in similar contexts to mean something far narrower,” the judges added.

“We conclude that to allow the government to collect phone records only because they may become relevant to a possible authorized investigation in the future fails even the permissive ‘relevance’ test.

“We agree with appellants that the government’s argument is ‘irreconcilable with the statute’s plain text’.”

The ruling, one of several in federal courts since the Guardian exposed the domestic bulk collection thanks to Snowden, immediately took on political freight.

Senator Rand Paul, a Republican presidential candidate who has made opposition to overbroad surveillance central to his platform, tweeted: “The phone records of law abiding citizens are none of the NSA’s business! Pleased with the ruling this morning.”

*

Meanwhile, Ed Pilkington reports in The Guardian that the ACLU has sued Virginia county police for storing data from license plate readers, the country's first legal challenge of its kind:

The ACLU in Virginia has launched what is believed to be the first legal challenge in the country against police for storing vast amounts of personal data obtained by scanning car license plates.

The Virginia branch of the civil liberties group is seeking to stop the police department in Fairfax County, just outside Washington DC, from storing the details of hundreds of thousands of vehicle license plates which it argues is an unacceptable invasion of privacy.

The lawsuit says that the data, which includes the date, time and location of each vehicle scanned, is held for up to a year even though most of the individuals caught up in the data grab are suspected of no criminal activity.

Concern about the practice of law enforcers indiscriminately scraping and storing data from vehicles using so-called license plate readers (LPRs) has grown steadily in recent months. Research by the ACLU nationally has shown that millions of Americans are now subject to such surveillance, the fear being that the information can be used to build up intrusive profiles on individuals and their behavior.

Earlier this year it was revealed that the Drug Enforcement Administration, in collaboration with another federal agency, had planned to use the automatic technology for surveillance of people attending public gun shows.

“Every time the government holds large amounts of personal information about individual people, there’s a potential for misuse. We’re very concerned about large databases being compiled that allow the movements to be tracked of ordinary Virginians,” said Rebecca Glenberg, legal director of the ACLU of Virginia.

Public records have shown that during the 2008 presidential election cycle, Virginia police used LPRs to monitor people attending rallies by Barack Obama and the Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin. They also tracked vehicles crossing the border between Virginia and Washington DC at the time of President Obama’s first inauguration.

Glenberg said: “In the abstract, license plate scanning may sound harmless, but many people would be alarmed to learn that law enforcement keeps whole lists of people engaging in specific political activities.”

Fairfax County did not immediately respond to a request for comment from the Guardian.

License plate readers are usually attached to police patrol cars or on fixed posts, and are capable of recording thousands of plates per minute. The federal government has encouraged the proliferation of the technology with grants doled out by the Department of Homeland Security and other agencies.

The overt reason for collecting the data – to which the ACLU does not object – is to compare number plates against a “hot list” of stolen vehicles and criminal suspects, including sex offenders and fugitives. What civil liberties groups do object to is the passive use of the data and its long-term storage, even where no criminal activity is involved.

In February 2013, the Virginia attorney general’s office released its legal opinion that data collected by LPRs should only be stored if it “specifically pertains to investigations and intelligence gathering relating to criminal activity”. On the back of that advice, the Virginia state police stopped using LPR technology and purged its databases of any information other than that prompted by active criminal investigations.

But individual police departments in counties across the state have continued passively to gather and store the data, prompting this week’s lawsuit which is seen as a test case in a relatively new area of the law. In the case of Fairfax County, the police department is party to a “memorandum of understanding” in which it shares all its license plate data with an unknown number of law enforcement agencies in the Washington DC area, thus compounding the privacy intrusions.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments