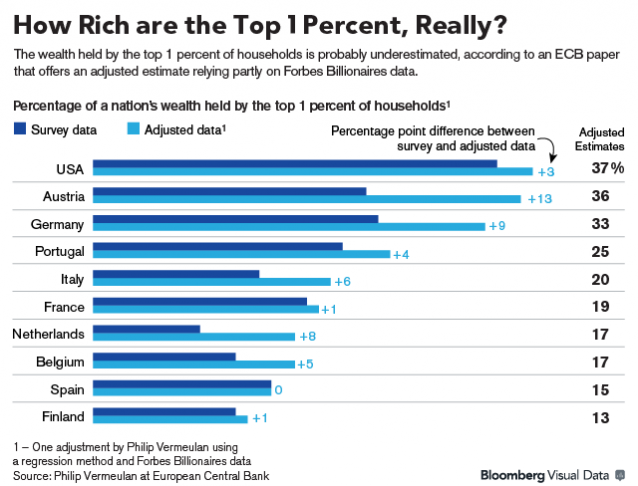

We already know that the top one percent of income earners are getting more and more money while things stall at the bottom. But even so, the sheer amount we think they have is probably an undercount because it’s so hard to measure.

The wealth of the most well off people is under-counted because they hide it in tax shelters, keep it in foundations and holding companies, and don’t respond to questionnaires, according to a Bloomberg analysis of recent research.

Economist Gabriel Zucman had initially estimated that the top 0.1 percent, who have at least $20 million in net wealth, held 21.5 percent of all wealth in the United States in 2012, but after estimating what is hidden in offshore tax havens, that number is more like 23.5 percent.

Survey data is also faulty because the sample sizes are so small. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances found that the one percent held 34 percent of wealth in 2010, but that’s more like 35 to 37 percent, according to a new paper.

Data for the European ultra wealthy could be even worse than in the U.S. because they stash more wealth in offshore accounts.

Given the under-counting of data, this likely means that findings that wealth inequality had been dropping are wrong. With preliminary adjustments, the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, stayed basically the same over recent decades.

“With a ‘top heavy’ adjustment, the decrease in inequality — present when we use all other adjustments — almost entirely dissipates,” according to a paper Bloomberg cites from December.

This presents a few problems. One is that if the rich are under-counted, they’ll end up paying less in taxes. Wealth held in offshore accounts costs the government $36 billion in tax revenue each year. “That’s enough to buy lunch for every student in New York City public schools for more than a century,” Bloomberg notes.

It also presents difficulties for finding solutions to income inequality. If income and wealth is more concentrated than currently thought, it may make a better case for changing the tax code to address it.

“There are potential implications for tax policy,” Zucman told Bloomberg. “If inequalities are higher than we thought, then maybe it can change views on the extent to which marginal tax rates should be increased on top incomes or the extent to which we should use other tools, like a wealth tax.”

The previous numbers that may have under-counted the disparities were still bad. The top 10 percent of American earners took home a record share of income, more than 50 percent, in 2012, and wealth inequality is now at least as bad as it was in the 1920s. While the disparities had been growing steadily since the 1970s, the recession made them even worse.

A chorus of voices have warned that these trends are harming economic growth, from researchers to the International Monetary Fund to those on Wall Street. But the damage may be even worse if the figures are all under-counted.

While Zucman is hopeful that bigger numbers will spur more policy action, there’s reason to be pessimistic about that idea. The one percent’s policy priorities diverge sharply from everyone else’s, but they have the loudest voice on Capitol Hill.

Lots of research has found that what the rich want from Congress, they get, while the less well off don’t get much of a say.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments