RALEIGH, N.C.—For a few hours every Monday, one of the black churches on the outskirts of town becomes a political beachhead. Today it’s Christian Faith Baptist Church on Hilltop Drive, conveniently about a mile from the Wake County Detention Center. I walk in shortly after 2 p.m., sign in as “media,” and pick up yesterday’s prayer program, which includes a Harper’s-style listicle of ominous numbers. The last of them:

21 million – estimated numbers of votes cast in North Carolina elections in the last twelve years

1 – number of cases of voter impersonation fraud that occurred in North Carolina in the last 12 years according to the State Board of Elections

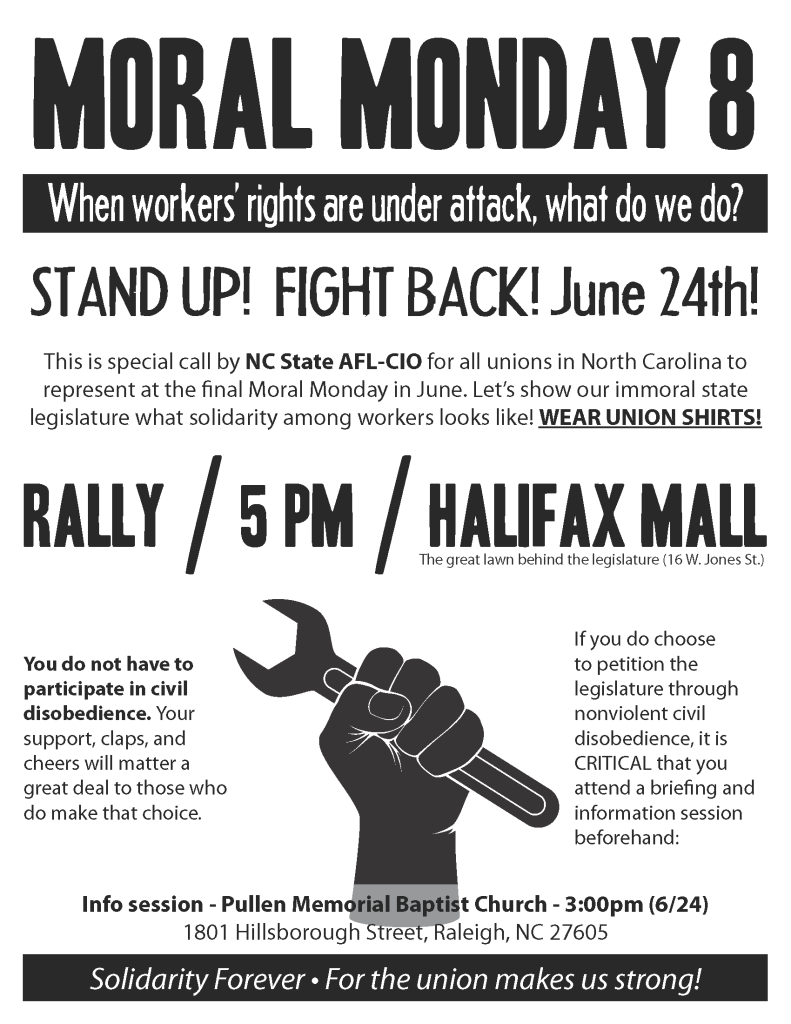

It syncs up neatly with today’s rally. For the 12th time this year, state NAACP President Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II will lead a few hundred protesters to the North Carolina legislature, where 90 or so will refuse to leave and be hauled away by police. Every week, they focus on a new piece of legislation from the state’s Republican House and Senate—background checks for welfare recipients, opting out of Obamcare’s Medicaid money, an end to long-term unemployment benefits, an omnibus abortion restrictions bill attached (for reasons of efficiency and bad PR) to a motorcycle safety bill. Every week, the legislation passes anyway.

Yet the reporters keep showing up and talking to Barber. As a PBS camera crew sets up in the chapel, two volunteers wheel a yellow-and-black NAACP logo in front of the pulpit, to frame the shot. Barber, a former linebacker who steadies his considerable bulk on a wooden cane, makes small talk with his interviewers. They want to know how many people they’ll be filming.

“The thing about a moral movement is that you don’t measure numbers,” says Barber, opening the buttons of his long suit coat. “You say you’re gonna get 5,000. Everybody focuses on whether you got 5,000. In a moral movement, it takes one person whose constitutional rights are violated, or one person who’s offended in some way. Think about Dr. King. Birmingham—that was started by 50 people.”

Barber sits for one interview, then another, then talks to me, offering only slight variations on a theme. The goal today is to occupy the Statehouse until police start arresting protesters. It’s not to stop the new voter ID bill, which was dropped at the end of last week, because Moral Monday protesters aren’t taken seriously by the solid Republican majority in the legislature. State Sen. Thom Goolsby calls the movement “Moron Monday.” Gov. Pat McCrory has accused them of “cussing” him out. Sen. Tom Apodaca, who runs the rules committee, has announced the progress of these bills with all the confidence of someone who can’t possibly lose re-election.

“They haven’t moved,” Barber tells me, after I ask what the protesters are actually winning. “The people have moved. Now less than one in five North Carolinians agree with them. Moral Monday is more popular than them.”

This theory, that a boldly obnoxious “citizens movement” can bring down the elected class, gets a new text every year or so. In the summer of 2009, to the horror of Democrats, Tea Party activists swarmed congressional town halls and begged them not to pass the Affordable Care Act. The swarmers won. In the winter of 2011, progressives occupied the Wisconsin capitol until the newly dominant Republicans found a way to pass a “budget control” bill that broke most collective bargaining rights for labor unions. The Republicans won, crushing an attempted recall of Gov. Scott Walker and keeping control of the legislature thanks to their own favorable gerrymander. Then came the Occupy movement, then came the protests of Texas’ abortion bill, all of it resulting in a legislative defeat but plenty of media.

That’s what’s happening in North Carolina, with a twist. Barber is a veteran organizer who became the NAACP’s leader in the state in 2006 and jumped feet-first into the Duke Lacrosse rape scandal. His credibility survived, and by 2011 he was celebrating a Democratic rout of Wake County school board members who had ended a busing program. When the new Republican legislature started working through its backlog of conservative bills, Barber was ideally positioned to embarrass them in front of national TV cameras.

So he does. As we finish talking, volunteers for today’s rally and civil disobedience walk into the pews. “Marchers on the right,” says a volunteer. “Civil disobedience on the left.” Out in the lobby, another volunteer is ripping up green gingham cloth to create armbands for the people who’ll get arrested. “It’s what was on sale at Marshalls,” she explains. Outside, as activists stream into the church, seven members of an extended family wait to meet Barber—he wants to congratulate them for joining the cause last week.

“It was awesome getting arrested,” says Alisa Denbow. She worked at a gun shop—Sovereign Guns—got laid off, and joined the cause when the Republicans ended long-term unemployment benefits. “I’ve never been arrested, but I felt really good about standing up for what we believe.”

“Half of the officers said they agreed with us!” says her cousin Dennis Bailey.

“Well, the one I had wasn’t too nice,” says Denbow. “He about ripped my arms off. He tightened that cuff so frickin’ tight I couldn’t feel anything.”

Denbow and Bailey are white, as are most of the people training and rallying today. The activists have their theories about this. “Six years ago I’d march with Rev. Barber and you could pick me out of a crowd,” says Timothy Tyson, a Duke professor who’ll be cooking lamb stew for the protesters when they get out of the detention center. He teaches civil rights movement history, he had a book about his father’s activism adapted into a movie, and on a previous Moral Monday, he’d gotten himself arrested. “There might have been three white people at one of those protests. Now, I think the people getting arrested are the people who can afford to, a lot of older people.” Younger people or black people might worry more about acquiring Google-accessible mug shots.

A good crop of younger people make it to the civil disobedience session anyway. After they learn how to conduct themselves and which attorneys to talk to afterward, they join the generally gray-haired activists in rows behind Barber for a press conference-cum-sermon. Barber points to veterans of the 1960s marches for civil rights—one of them “was there with those who said we’re gonna march from Selma to Montgomery to create a crisis that was going to save the possibility of our voting rights.” And that’s why they’re going to get arrested today. The media won’t cover the predictable march of conservative legislation through a conservative legislature. They will cover an actual march that ends in a flurry of white plastic handcuffs.

So the marchers are off, and at 5 p.m. they join the public, jail-free part of Moral Monday. Halifax Square, a pleasantly anonymous green space in front of the Statehouse, is around half-filled with a few hundred protesters. They move closer to the center of the field as the July sun is obscured by clouds. Some hold up pictures of Trayvon Martin. Some hold up parasols decorated with slogans against the “War on Women,” mementos from the week before, when the legislature rammed the “motorcycle abortion bill” through. “That crowd went all the way back to the Statehouse,” says Leslie Boyd, a health care access activist who was arrested after the state opted out of Medicaid expansion money. “Seeing these middle-aged and older women smiling politely, walking out in handcuffs, that was just incredibly inspiring.”

The field is littered with the noble failure of previous protests. A few days earlier, the Senate passed a ban on foreign law generally understood to be a prohibition on “Shariah courts.” Archie Mustafa-Gordon, a retired corrections offer and member of the Nation of Islam, stands with four fellow Muslims holding plaintive signs, asking people to understand what Shariah is. “They’re misinterpreting what’s in the Quran,” he starts to say—but just then, a Democrat bounds onto the stage to announce that the voter ID bill they had been protesting will be replaced by an omnibus bill, with even more restrictions.

“They put all the bad stuff together, and we’re gonna fight it!” says the speaker. “Do not rig the election if you can’t win it!”

Mustafa-Gordon frowns. “Right, right, we keep hearing that,” he says. “But the thing is, we voted them in there.”

The rally keeps to a tight schedule, anchored by another rousing Barber speech with call-and-response slogans.

“Somebody say the right to vote--”

The right to vote!

“--is sacred--”

Is sacred!

“--and this fight”

And this fight!

“--is personal.”

Is personal!

“When Sen. Apodaca describes the Voting Right Acts as a headache, he sounds like Strom Thurmond or George Wallace or something! He needs to get his heaaaaad fixed and his heaaaart regulated—he thinking like he’s in the 19th century!”

A little bit after 6 p.m., the rally comes to an end, and the crowd needs only a little guidance for the next step. It parts, cutting a path from the stage into the Statehouse. The people getting arrested and the people supporting them march through, high-fiving and hugging and posing for pictures as they go. Expressionless police officers watch them head in, knowing what comes next. Organizers stand inside the building, barking commands: “If you have a green armband, go left! Everybody else go right.”

The crowd, finding its way up some stairs and through hallways, fills both levels of the atrium between the legislative chambers. Those on the third floor can peer past a bronze chandelier and see Barber and anyone else who wants to speak, without amplification, into news cameras. At some point, even though the legislature is gone for the day, they’re going to get arrested, so the trick is keeping the mood up until the cops play their part.

So most activists say something short and personal. A student from Wisconsin is greeted with cheers, even though the idea that this crowd is inflated by “outsiders” has been a Republican knock against them. Harold Timberlake, a pastor from Charlotte, opens his iPhone and reads Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in its entirety, affecting a spotless King impression.

It’s not until 7:12, when a hesitant older woman starts to speak, that the police loudspeakers announce that “this building is closed” and anyone not wanting to be arrested has five minutes to leave. The reaction is unfailingly polite. Those who really want to leave do so immediately, in a slow push out of the building. The 90-odd civil disobeyers stay put, facing the police officers, one of whom dutifully points a camcorder at them. They run through the chants:

Tell me what democracy looks like?

This is what democracy looks like!

The people, united, will never be defeated!

Whose house? Our house! Whose house? Our house!

At 7:17, the arrests begin. Some of the protesters closest to the police pre-emptively clasp their hands, prepping for the cuffs to come on. There’s no rush—the process is so deliberate that the protesters run through the standard peace and civil rights anthems and start depending on a man who knows a few union ballads.

The arrests are still going on at 7:45, when I follow some of the non-arrested protesters outside to face the prison bus. There are two buses backed up to the building, waiting to be filled for the short drive to the detention center. The other side of the street, abutting a parking lot, is filled up with supporters singing and chanting and being supplied with water, as black pastors walk up and down the street, revving them up. I turn away from the street for a second, just as a massive cheer goes up. Joggers, half of them shirtless and well-toned, are running past the protesters and giving the thumbs-up.

“They do it every week,” says protester Cathy O’Neill, wearing one of the “Jailed for Justice” T-shirts that started going on sale a few weeks ago. “It’s usually the same people, going for a run and putting us on the route. They’re fantastic.”

O’Neill and I wait for 30 minutes as the arrests finally conclude. She speculates that the state’s trying to wait out the pesky singing protesters across the street. The first bus only starts to board as the sunlight fades. It loads from the back—there’s no way to see the people being arrested. The crowd starts cheering anyway.

“Thank you! We love you! Thank you! We love you!”

As the second bus loads, I drive over to the detention center, an impressively bland fortress on the outside of town with plenty of parking. The “welcoming crew” is already there—the group of veteran protesters who’ve been through this plenty of times, and the lawyers who can notarize documents as the civil disobeyers exit with their personal items and court dates.

One of the simpler and more rewarding tasks goes to Dick Reavis. He’s a professor of English at North Carolina State University, but before that, he wrote what he calls “adventure journalism” for Texas Monthly; before that, he worked to register voters in Alabama. It was there, in 1965, that he was arrested and sentenced to six months of hard labor.

“It was a segregated prison, and they weren’t about to put me into hard labor with the black prisoners,” he remembers. “So I spent three weeks reading Socrates.”

As the protesters come out—starting at 9:12 p.m.—Reavis gives them buttons commemorating their service.

I Went to JAIL With Rev. Barber 2013

It’s all gotten quite neatly regimented. After that first round of processing at the Statehouse, prisoners are brought to a common room, given blue arm bands—“to denote that they’re political prisoners,” says Reavis—and nudged out quickly. People arrested in the first weeks remember waiting until 4 a.m. to get out of jail. The state’s goal now is to cycle the interlopers out, as quickly as possible. The protesters’ goal is to keep doing this, as long as the legislature is in session, then take the “Moral Monday” brand on the road, to each congressional district. The goal, after that, is to win the 2014 elections.

“People are going to suffer though months without unemployment insurance, without the Medicaid expansion,” says state Sen. Earline Parmon, a member of the welcoming committee. “They’re going to understand that the brand ‘smaller government,’ means less services to people. Look, the legislature is at 49 percent disapproval right now, with independents, and you’re going to see those numbers rise.”

The prisoner releases keep on happening, in short bursts, and people who are hungry are driven back to Christian Faith Baptist Church. The rooms usually used for Sunday school are given over to a potluck dinner. Tom High, a retiree, waits near the door to hand out plastic plates and silverware; a retinue of black women applaud when someone arrives with one of the “I Got Arrested” buttons.

In between servings, High speculates about “the positive things the movement can focus on next” so it’s not just a protest movement that fails to stop the legislature but drives down its approval numbers. Maybe a ballot initiative. Maybe an aggressive public finance law put to the voters.

There’s no consensus about that yet. The consensus is only that the protests are working, and that Tim Tyson’s lamb stew is delicious. At 10:30, the people who got arrested are still arriving and enjoying the spread, talking about how inspiring the whole drama was.

“We heard good things from the people processing us, actually,” says a college student from Greensboro named Noelle Lane. “The magistrate told me: I’d love to be on your side next time.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments