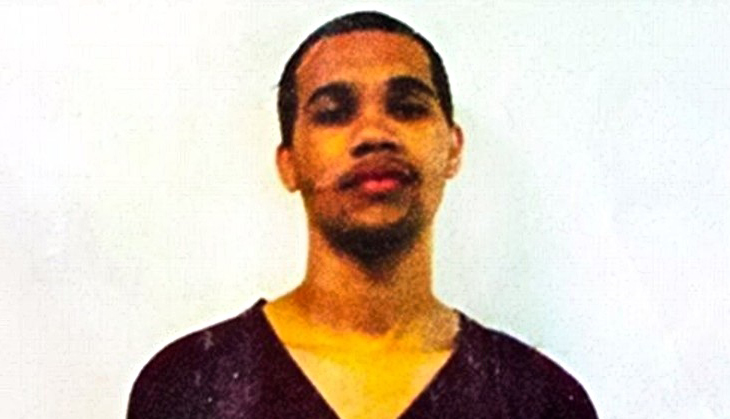

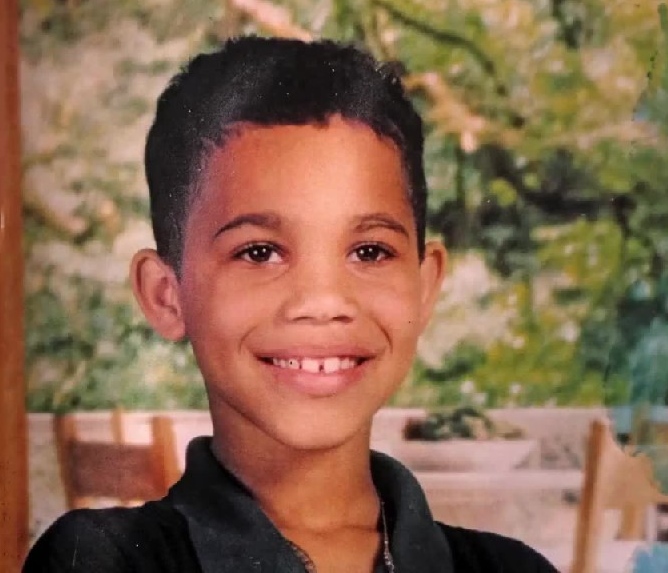

Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell, as one of his last acts in office recently, reduced the sentence of a 23-year-old African-American inmate named Travion Blount to 40 years in prison, making him eligible for release at age 55. Blount was serving six life sentences plus 118 years in prison without parole. His crime was participating in an armed robbery in Norfolk, Va., at the age of 15 along with two older friends, both aged 18. The three young men forced partygoers to surrender their cellphones, money and marijuana at gunpoint and were caught almost immediately by police. No one was killed or injured.

The two 18-year-olds, Morris Downing and David Nichols, accepted plea deals and received sentences of only 10 and 13 years each. But Blount decided not to plead guilty and instead requested a trial. The Virginia judge in his case issued one of the harshest sentences ever handed down to a juvenile in the United States for a non-homicide-related offense, equivalent to four felonies for every person who was present at the party.

Marc Schindler, executive director of the Justice Policy Institute, told me in an interview, “We are seeing in this country over the past 30 or 40 years a significant ratcheting up in the severity of penalties within our justice system, and [Blount’s case] is an example of that.” Schindler explained the draconian sentence as “a combination of mandatory minimum sentences and extremely harsh sentencing, including the ability to have young people prosecuted in the adult criminal justice system ... even if no one was hurt.”

Since Blount’s conviction and sentencing, the Supreme Court has realized the injustice of handing extreme sentences to juveniles and ruled against life-without-parole and death sentences for youth. Schindler noted that “young people generally don’t have the ability to comprehend, to make the types of decisions, and to assist in their defense as adults would have.” Sadly, the rulings were made after Blount was already serving his time.

Today there are tens of thousands of young people in American prisons. About 70,000 minors are locked up in juvenile facilities, some of which, according to Schindler, “are decent places that are trying to provide rehabilitation and treatment and which are getting good outcomes.” But, he cautioned, “There’s a lot of work that needs to be done in the juvenile justice system to improve that program ... [even though] there is the attempt and the goal of rehabilitation.”

The situation is far worse in adult prisons. About 200,000 Americans under the age of 18 are prosecuted as adults every year. Schindler plainly called it “bad public policy,” because “young people are subject to physical and sexual assault, and more likely to attempt or commit suicide when they’re in an adult jail or prison, and they come out worse than they went in, and that’s really in some ways no surprise because of the surroundings and what happens in those facilities.” He cited the sad reality that “young people who are prosecuted as adults are more likely to commit offenses when they come out, more likely to do so quickly and more seriously than similarly situated young people who are handled in the juvenile justice system.”

Public opinion over teens in adult prisons has shifted since the “tough-on-crime” approach of the 1990s. Schindler noted that “we’ve actually seen the pendulum swing back. Twenty-three states in the last 10 years have changed their laws to make it more difficult to prosecute young people in the adult justice system and to hold them in prisons and jails.”

Virginia is one of a handful of states that still allows minors to be sentenced to life in prison without parole. The state justifies this in spite of the Supreme Court rulings, because it has a policy called “geriatric release,” which means that an inmate who has served at least 10 years of his or her sentence and is 60 years of age can apply for early release. A member of Virginia’s parole board told the Richmond Times-Dispatch that the policy “was really focused on people who were going to get very long sentences at a young age so they would have some opportunity to be released.”

Until his sentence was reduced to 40 years over the weekend, Blount’s only hope was for a possible release at the age of 60 under the geriatric release program. But even that would have been highly unlikely given that only 15 people have ever succeeded in being approved for release.

On the other hand, if Blount had accepted the original plea deal offered to him, it is likely he would have been halfway through serving his sentence by now. But, because he chose to go to trial, against the advice of his own attorneys and the prosecutor and judge, he found himself with a sentence so extreme as to defy all logic and common sense.

But Blount, like all Americans charged with crimes, has a fundamental right to a fair trial. “Unfortunately,” lamented Schindler, “the system is set up in such a way that it pushes most people to accept plea bargains. Over 90 percent of the cases in criminal courts throughout the country are resolved through a plea bargain unless they’re dismissed. If cases went to trial in significant numbers, the system would literally shut down.”

Instead of being a poor black kid, what if Blount had been white and wealthy? What if, instead of committing armed robbery, he had killed four people? A recent case involving a white, wealthy 16-year-old in Texas who killed four people while driving drunk attracted a brief bout of media coverage for the defense’s successful use of a dubious mental affliction called “affluenza.” This essentially means that the young man’s wealth clouded his understanding of the consequences of his actions to such an extent that he was not responsible for his crime. The juvenile court that tried him thereby privileged him for being privileged, and sentenced him to 10 years’ probation and private therapy costing his parents nearly half a million dollars.

Schindler considered it quite appropriate to bring up the double standards of race and class, saying, “In our justice system generally, those who are subject to these really draconian penalties, such as life sentences or very long sentences for drug offenses, disproportionately are poor people of color, African-American primarily, and Latino.” He went further, noting, “I think that there’s a serious question about whether any of these sentences and penalties would be in place if they disproportionately impacted white people.”

But he was reluctant to conclude that the rich white Texas teen got off too lightly, saying, “I think that what should happen is that in all cases we should take an individual look at what is in the best interest of a young person and their capacity to change.”

Schindler is hopeful that Terry McAuliffe, Virginia’s new Democratic governor, could still win a pardon for Blount or a further reduction of his sentence, pointing out that he’d like to see the decision made “based on the ability of Travion to change.” He added, “I think that’s already seen to be happening. He is—from what I understand—a more mature, more thoughtful person now, and he understands what he did. He takes responsibility for his actions, but understandably feels like this [sentence] is just way too disproportionate.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Barry Jones replied on

Song in support

The Ballad of Travion Blount

© 2016 Adisa Branshouté

The Ballad of Travion Blount really is

‘bout a boy who took some stuff—not his:

Sixty bucks, three joints, two phones, then run,

But Travion never hurt anyone.

Two big men talked him into that crime.

They pled—got ten an’ thirteen years’ time.

But Blount, at the age of fifteen, a child,

Wanted and got a three-day trial.

Guilty as charged, his sentence ran:

Six consecutive life terms and

Over one hundred years of three hots and a cot.

More time for less crime than a child ever got.

Years went by, Blount appealed—and bled.

Then one Virginia Governor said:

“Thirteen? Ten? For two big men?

Here’s forty years, son, don’t ask again.”

But everyone said, “That’s insincere!

One of those men got out last year.”

Then Federal Court cut Blount some slack.

The Fed said, “Forty? Hey kid, that’s wack.

Virginia must change, or better explain.”

But Virginia gave Blount forty years again.

In prison forever, Blount hurt no one.

Killers and rapists surround Travion.

And one co-defendant’s free as snow,

An’ the other’s got three years to go.

Is it fair? Is it right? Or is that the way

Kids get jacked in the USA?

For equal justice some still hunt.

That’s The Ballad of Travion Blount.

©2016 by Adisa Ivor Branshouté

C/o P.O. Box 616

East Canaan, CT 06024