ISTANBUL – Turkey’s strongman prime minister has mobilized the power of the state to head off another popular uprising against rising authoritarian rule.

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan took no chances this weekend by calling up 25,000 riot police, 50 armored riot control trucks and canceling public transport in an effort to head off the one year commemoration of the Gezi protests.

On the eve of Saturday’s anniversary, Erdogan appealed to young people to stay away.

“One year later, people, including so-called artists, are calling for demonstrations, but you, Turkey’s youth, you will not respond to the call,” Erdogan told a crowd of a thousand young people in Istanbul. “These terrorist organizations manipulated our morally and financially weak youth to attack our unity and put our economy under threat.”

People turned up anyway – at great personal and legal risk – to occupy a public space and make their voices heard. Last year’s unrest began when the government arrogantly rolled out plans to raze a public park to make way for yet another shopping mall. The result was millions rioting in cities across Turkey.

“We are here due to basic matters that have to do with humanity and freedom. There have been a lot of dead people and the state looks the other away, and is doing nothing about it,” said 25-year-old university student Merve Gedik, who stared down a phalanx of riot police on Taksim’s main pedestrian street on Saturday.

It’s not just the young people who are dissatisfied with Erdogan’s one-man, one-party domination of Turkish politics, but middle class Turks fed up being dictated to by a party that proscribes a conservative religious ideology for the whole citizenry.

Haluk Abaoğlu, a 56-year-old marketing executive, says the prime minister’s insecurity stems from the blood on his hands from the deaths of 10 protesters and more than 8,000 injured since the crackdown began last year.

“It is our natural right to be able to walk to Taksim today. We are now everywhere. Everywhere we stand for Gezi/Taksim resistance,” he said wearing a t-shirt that reads şehit, Turkish for "martyr" – in recognition of those killed in clashes between protesters and police. “Prime Minister Erdogan is guilty and he knows it. He is the type of person who is an enemy of mankind. To be able to continue with his dictatorship, he is using this kind of police force in his own interest.”

Police on Saturday attacked and cleared the streets. True to Erdogan’s word there was "no mercy" and tactics were if anything more brutal than expected as unarmed protesters were cleared with tear gas, water cannon – and in a new development for Turkey, swinging batons, which police used with brute force to clear the streets in minutes.

Predictably the crackdown was met with international condemnation and calls for restraint.

“I condemn the excessive use of force by the Turkish police against demonstrators and journalists,” Nils Muižnieks, Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner, said in a statement Sunday. “Yesterday’s events add to the list of cases in which the handling of demonstrations in Turkey has raised serious human rights concerns.”

But veteran observers say the police crackdown represents a crackdown by a regime that’s insecure because it’s facing something it doesn’t understand and can’t control.

“Gezi is really something which concerns the prime minister and his government – it’s not over at all,” said Cengiz Aktar, a research scholar with the Istanbul Policy Center at Sabanci University and one of the leading figures in last year’s calls to resist the redevelopment of Gezi Park.

“The spirit of Gezi, as it is called, is very much there. Because Gezi is a type of opposition, type of protest, that the political establishment – including the opposition – is totally incapable of understanding and addressing.”

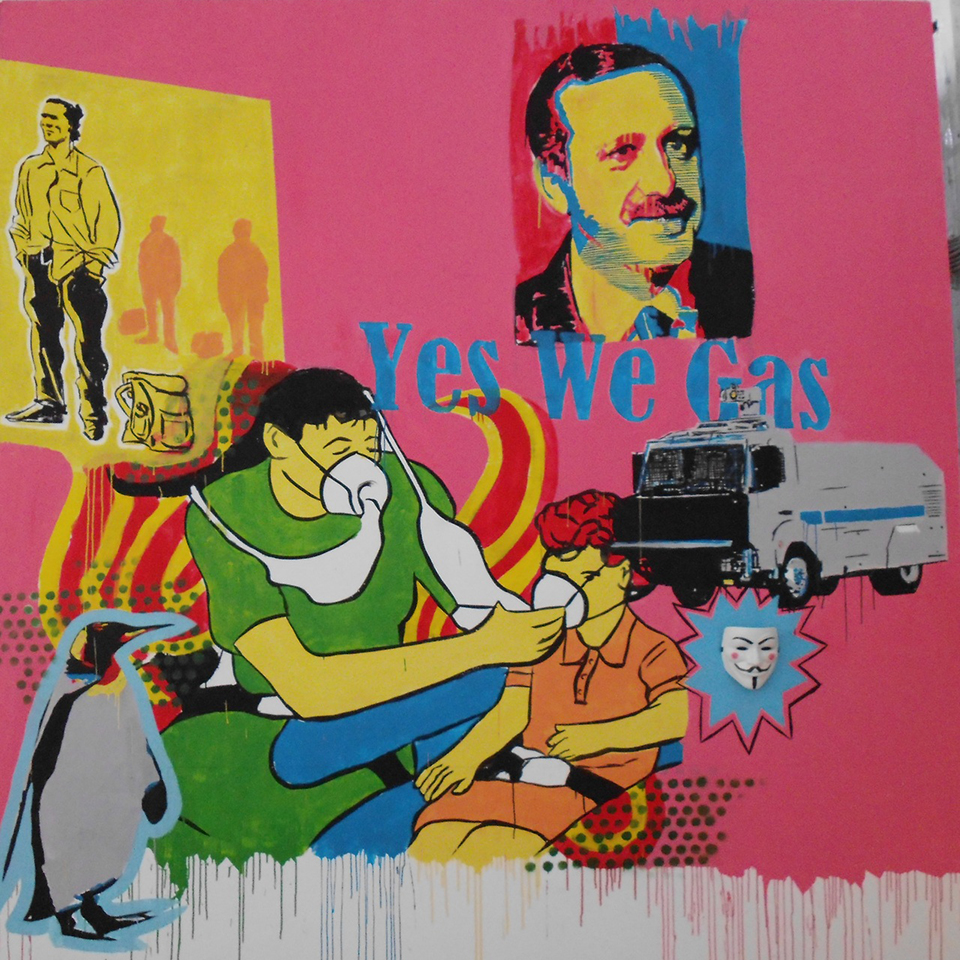

Artistic Eruption

During last year’s occupation of Taksim Square there was an explosion of creativity after fear of state oppression over lifestyle, political views and cultural association was lifted. The result was a fountain of creativity that had been latent for so long among Turkey’s younger generation.

“It was the end of fear,” Aktar said. “The Turkish public through Gezi managed to reject physically this empire of fear that was slowly imposing itself on society.”

Artist and photographer Denizhan Ozer, who this month co-curates an exhibition on Gezi Park artwork, agreed.

“Gezi really changed a lot of young artists who didn’t have self confidence,” he said. “After Gezi they have self-confidence and it broke down a lot of walls.”

Ozer and fellow artists created the exhibition because traditional news media’s shelf-life is limited.

“But artwork lives on forever if it’s really good – that’s why art is so important,” he said.

Turkey remains the largest prison for professional journalists and due to media consolidation and holding companies with financial ties to the government, its status has been downgraded. An exception is its lively satirical cartoon magazines which, since Ottoman times, has held up a mirror to the political elite whether sultan or prime minister.

“We’re not the opposition to the government, we’re always in opposition to the stupidity of the politicians so whoever comes to power, it doesn’t matter,” said illustrator M.K. Perker whose work appears weekly in Penguen, a full color magazine with about 70,000 circulation.

Perker says even though they deal in cartoons, the subject matter is often serious and addresses matters of life and death.

“It is always going to be important because we have to deal with very harsh situations, political developments,” he said. “We try to make something beautiful – it’s a clash of feelings and ideas – at the same time using something very artistic in a very rough neighborhood.”

Penguen is independently owned and is not beholden to the same financial pressures like most newspapers or television networks whose parent companies are beholden to government contracts and regulation to turn a profit.

Baris Uygur, a humor columnist at Uykusuz (sleepless), which was established by a group of staffers who left Penguen in 2007, says only the humor magazines have the independence to speak truth to power.

“Every media company is actually a PR department. It just functions as a PR department of a larger holding that has construction and energy businesses,” he said.

Events move so quickly, lurching from scandal to scandal, making it a complicated and challenging time to be a chronicler of current events, Uygur says.

“Things move very quickly here so even being a weekly magazine isn’t enough.”

Despite vocal opposition in Turkey and abroad, Erdogan’s AK Party remains unrivaled as the most powerful populist force. This summer he’s expected to run for president and carve out a long-term position of unchecked power as the country’s strongman leader.

But his critics point out that while he is able to command electoral support – his party polled about 43% in the March local elections – the economy remains his greatest vulnerability.

“We should be capable of calling a spade a spade. Turkey is slowly but surely heading towards a very authoritarian state and authoritarian society because 43 percent of the people approve,” Aktar said. “This chain of happiness will continue as long as the economy will continue to function. We have very clear signals that economically speaking that Turkey will be having tough times in the decades to come.”

That’s because Turkey’s economic miracle is predicated on foreign investment in large-scale construction projects – shopping malls, residential blocks, bridges, passenger rail, power plants – all financially stimulating in the short-term, but providing almost nothing in the way of a sustainable economy once the concrete is poured and the project is finished.

Even Uygur, who writes for comics and is not a trained economist, can see this reality.

“We have a booming economy and like all booming economies I predict: it’s a bubble booming,” he said. “We have spent a lot and that’s the reason behind the ‘economic miracle’ in the last 10 years, but we didn’t really put anything towards a sustainable economy in that sense.”

Aktar reflects a mixture of optimism and pessimism about the country’s future. On one hand he sees the so-called Gezi spirit and indefatigable new force in society, but on the other hand the political elites' efforts to quash it could ultimately become self-destructive for Turkey as a modern society.

“This government did a lot of good things, we had really bright achievements in the first part of its tenure and they spoiled it, badly,” Aktar said. “Turkey was representing a kind of model in the eyes of world public opinion where one can be Muslim but modern and democratic, and this opportunity at least for the time being is wasted, unfortunately.”

With additional reporting from Ricardo Ginés Echeverría in Istanbul.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments