A federal court in California has ruled that a surveillance tool widely used by the FBI to obtain information on Americans without court oversight is unconstitutional because the gag order that accompanies it violates the First Amendment.

The ruling by Judge Susan Illston of the Northern District of California would bar the issuance of national security letters — a form of administrative subpoena — on constitutional grounds.

The ruling on the 1986 statute has been stayed while the government weighs an appeal.

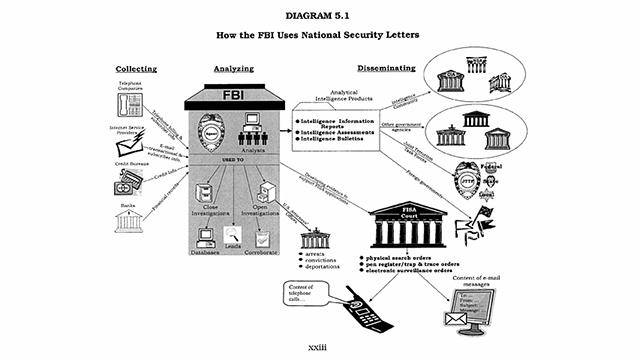

NSLs allow the FBI to ask Internet companies and other electronic communication service providers to turn over subscriber information on American customers and to demand that the providers keep the fact of the letter secret — including from the target.

To issue an NSL, a supervisor need only certify that the records sought are relevant to an authorized national security investigation. No warrant is required. FBI officials have said that such flexibility, granted in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks, is crucial to preventing future attacks.

But the letters have been controversial. The Justice Department inspector general found several years ago that the FBI abused its authority to issue NSLs, often failing to justify the need for the surveillance.

Although the bureau has said that it fixed the problems, questions surround the use of the gag order and the law’s lack of clarity about what type of information may be obtained under what legal standard.

“NSLs are unique in their invasiveness and lack of judicial oversight,” said Matt Zimmerman, a senior staff attorney with Electronic Frontier Foundation, which filed suit on behalf of an unnamed telecommunications company.

Justice Department spokesman Dean Boyd said the department is reviewing the judge’s order. He declined further comment.

The FBI was issuing an average of 50,000 letters a year after the 2001 attacks. In 2011, according to the Justice Department, it made 16,500 requests for data on 7,200 Americans.

In her ruling, Illston conceded that there might be situations where disclosing the receipt of an NSL could jeopardize an investigation. But where no such risk exists, she said, “thousands of recipients of NSLs” are nonetheless gagged, “rendering the statute impermissibly overbroad.”

She said the FBI’s “pervasive use” of gag orders, combined with a failure to demonstrate the orders’ need to protect national security, “creates too large a danger that speech is being unnecessarily restricted.”

A federal judge in New York reached the same conclusion as Illston in a 2007 case involving a different provider. But that decision was narrowed on appeal.

An industry lawyer said that gag order aside, the statute is flawed by its ambiguity. “It’s overused,” said Michael Sussmann, a partner at Perkins Coie. “It’s overbroad.”

The best result, he said, would be for Congress to clarify the statute to detail what type of information may be obtained without court oversight.

Electronic Frontier Foundation filed the case under seal in 2011. The plaintiff’s name has not been disclosed.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments