Any of the 15 South Sudanese refugees I meet may die this night attempting to stowaway in a vehicle and cross the English Channel. I am within 10 miles of the French port of Calais and it is now dark in the early hours of the morning.

Last month, Haroon Youssef, a 19-year-old Sudanese refugee, died falling onto the axel of a tourist coach while trying to make it north to Europe. Many others die suffocating in air-tight spaces. Yet if anyone makes it onto a vehicle tonight, their risk of death is smaller than before they made it here.

In action and rhetoric the U.K. government demonizes and attacks both refugees and migrants, as demonstrated by the country's "Go Home" vans, its border agency staff that stops ethnic minorities across London tubes, and even Home Office tweets celebrating the deportations.

Mainstream media often encourage the demonization of migrants. Yet their accusations can be easily revealed as myths based on falsehoods. A BBC report exemplifies the misrepresentation of refugees who are trying to get through Calais to the U.K.

The channel downplays the life or death situation facing migrants as a "cat-and-mouse game" they play with authorities, in which the migrants are the aggressors. This kind of narrative often fails to show any empathy with the refugees’ plight or analyze why they are fleeing their homelands in the first place.

The Journey to Calais

The 15 men I met in Calais, aged 15 to 26, have escaped genocide and war in Darfur and South Sudan. For a decade, human rights atrocities in their country have been enabled through tacit support of the U.K. government and Western corporations. Meanwhile, recent reports show continued land-grabbing in the region.

“This conflict is mostly ignored by the Western mainstream media,” refugee Abjoke Adams says. After leaving his homeland, Adams, like many of the others I spoke with, went to a UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) camp. “Here [at the camp] there is little food or hope, you cannot work and rely on aid,” another refugee tells me through his translation.

After the camps, many head north joining Congolese, Eritreans and Somalis who are also fleeing conflicts. Once at the Mediterranean coast, they cram into inflatable boats without engines. Every year, thousands of refugees die attempting to make the crossing. One of the men I met described how he had attempted to cross twice. The first time, after two weeks, Tunisian authorities returned him to Tunisia. On the second attempt, after six weeks at sea, he and 100 others were picked up by the Italian navy.

“Everywhere people are dying – 15 died on this boat,” he says.

In Italy, and then in France, the refugees can only get asylum status – meaning they cannot work or receive public services, so most of them are forced into begging. This pushes them north towards Britain, the Benelux countries, Germany or Scandinavia.

“We want to work, to be able to study, to have a future,” another refugee says, echoing a sentiment expressed by many in the camp. This particular group chose Britain because, as the ex-colonial power in their country, they have the impression that it respects human rights. They also know varying degrees of English.

When I first encountered the refugees last week, they were wary of my presence – not least because police often beat those attempting to gain passage across the channel, and they didn't want me giving away the location. But as I stayed longer, they were soon asking me questions about their prospects in Britain. I told them both how racism is increasing and refugee rights are being removed, but that they can find support from NGOs that can help them avoid detention centers and forced repatriation.

With unbridled spirit, one replies: “Even the possibility of a future feels like a 5-star hotel compared to Darfur.”

Conditions In the Camp

Later that night, I return to the main refugee camp in Calais. I sleep in a tent, with one blanket between me and the tarmac, and one blanket for warmth. Eight hundred people live semi-permanently like this, on a disused plot near the ferry port. Facilities here are sparse, including three temporary toilets and four outside taps.

Most refugees sleep in tents or makeshift shacks made from pallets, waste wood and tarpaulins. Charity services provide the refugees at least one meal a day, and activists also ensure the people get clothes, blankets and shoes.

Formerly, the refugees lived in camps closer to the port, differentiated by nationality. But these camps were cleared by French riot police on May 28, and the main camp in Calais is what remains.

“You see the bullshit life here. I don’t just want asylum and [to] stay in the camps or on the street. I want refugee status to get a job, go to school and think about a future," John Abdullah, from Afghanistan, tells me. "I know 11 languages. I bet I could do something.”

He recounts that his life was very good before America with NATO support invaded the country more than a decade ago in its search for the Taliban. He owned a shop in the Kunar province. After the invasion, he said, if he spoke with the Taliban the government would arrest and possibly kill him. But if he had dealings with the government, the Taliban would kill him instead.

Abdullah made to the U.K. in 2002 but was forcibly repatriated. Fearing for his life, he left again. His story of fleeing twice from a war zone is commonplace among others I speak to in the camp.

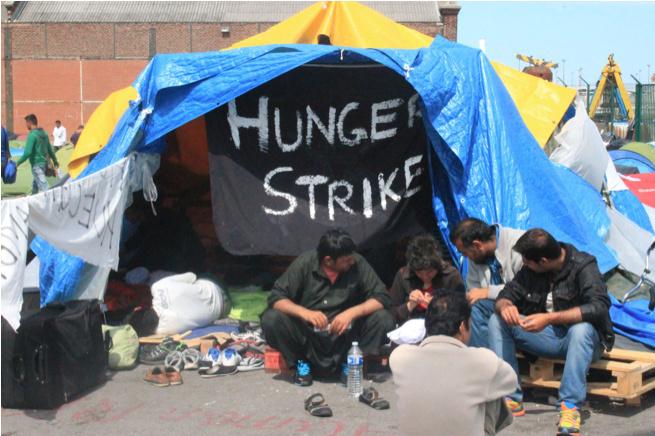

“We want to live not to die,” reads a painted banner outside the camp. Currently, there are 35 refugees on a hunger strike demanding that the British and French authorities open discussions on giving them legal status.

“We have not eaten for 13 days. You can see the situation here is very bad,” Mohammed Said says, dazed and clearly weakened from the experience, but still speaking with defiance.

“Nobody wishes to leave their country, but [they do it] to gain human rights. Now we don’t get any human rights in Europe,” he adds.

Said describes how the police regularly beat the refugees at the camp. One man I meet, Adam-Joseph Gabriel, shows me the dressing covering a bullet wound. He was shot by port security, he says, and an ambulance was not sent immediately.

“We are not happy, they are playing a game with us," Said says. "I’m sorry to say but they don’t care about us.”

If there is no response soon to their demands for legal status, the group says they plan to pour petrol on themselves and burn to death in a public act of self-sacrifice.

The hunger strike includes men from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria and Sudan – a unity that reflects how the camp has brought refugees together from across Africa, the Middle East and Asia. At the same time, there are assemblies in the camp, as well as sports games and other types of socializing. Sometimes tensions lead to arguments, as many jostle to be fed, and on occasion there are fights.

During my stay in the camp I am invited to one shack, where I take my shoes off and am treated to Arabic coffee by three Syrian refugees. They tell me the horrors of loosing members of their families, yet their joy in life seems phenomenal. One says that when he was caught once by a U.K. border guard, he turned her frown into a laugh by answering that he came to the U.K. to see her smile.

In the camp at Calais are also 30 Syrians – more refugees from the war than the entire U.K. has agreed to take, while Germany alone hasagreed to take in over 24,000 from the country.

To many, U.K. actions denying Syrians refugee status has undercut the government’s argument that it seeks military action in Syria for "humanitarian intervention" reasons. Meanwhile, the U.K. government is increasingly seen denying rights to the very people fleeing from that conflict.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments