“They were firstly about freedom and democracy, then about getting rid of Assad,” says Sami, speaking to me about the 2011 Syrian uprising which would lead to the brutal civil war that continues today. “I was studying [for] a Masters in Damascus. In September I joined a protest with friends. We were all arrested at gunpoint. If I had tried to escape I would have been shot.”

After his arrest, Sami (which is not his name, but a name we are using to protect his identity) was held for over two months and tortured daily. The relentless pressure led to his signing a false confession on terrorism charges. He faced 35 years in prison. But his family had paid a sizeable bail bond before his imprisonment, so Sami was able in the meantime to escape to Turkey.

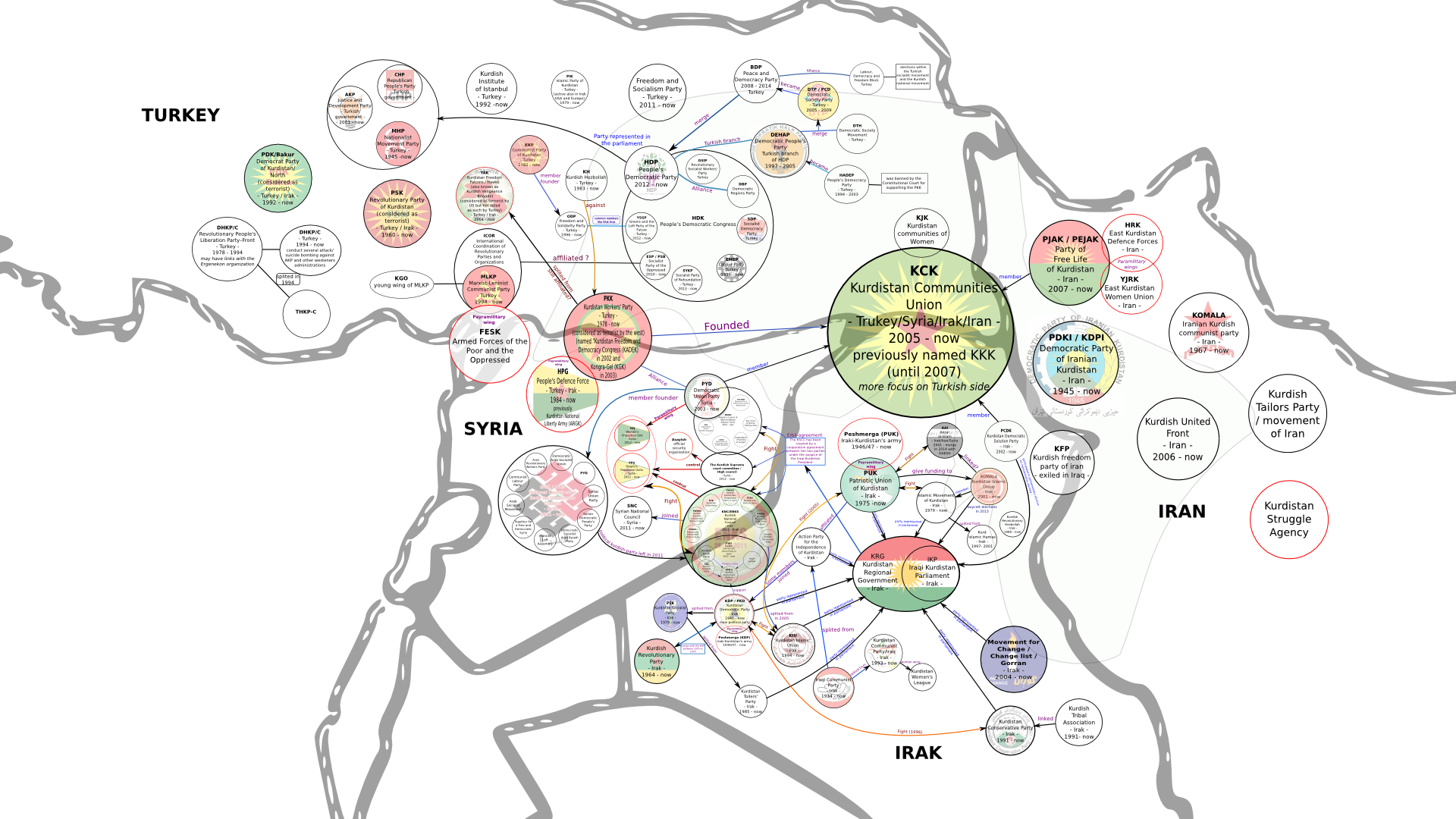

In late 2011, he crossed the border easily through the mountains of Cizîrê and travelled to an official border post for a visa stamp. Soon after, Sami, who is Kurdish, settled in Istanbul and started a Masters program at the university. But he knew he could not stay in Turkey, where state repression against Kurds is a daily fact of life. So, finally, he smuggled himself to Rojava, the Kurdish autonomous region in Syria, which has been on the frontline fight against ISIS.

Visiting Rojava

Now living in relative safety in Europe, Sami has escaped the world's worst humanitarian crisis and seen the start of a democratic experiment created in its ashes. His story is unique, but it relates to millions fleeing war and persecution. The West has backed Middle Eastern dictators, including Bashar al-Assad, and failed to support democratic movements like the one he initially took part in. At the same time, the story of refugees is often misunderstood in the West, where the corporate media frequently demonize those seeking safety and stability.

Sami tells me that back in 2013 he decided to return to his homeland, Rojava, the recently created Kurdish region outside of Syrian control, because he saw a new society formed around bottom-up democracy, one that was challenging patriarchy and capitalism. He was surprised to see Kurdish openly spoken and written there, since it was banned and he had had to learn it secretly as a child.

His first-hand account reflects what has been explained in the book Revolution in Rojava, the first extensive English account of the region, which inspired a four-part Occupy.com series earlier this year. Expanding in detail, Sami tells me how Rojava is challenging the traditional class system. Before, society was divided into landlords and farmers; Sami's background is from the landlord class, which previously took most of the profits from farmers toiling the land. Since the revolution, many from his family, particularly the older generations, are unhappy that the farmers both get to keep their labour and take on responsibilities in the bottom-up democratic system. Sami welcomes these social advancements.

Incredibly, the Rojavan revolution continues while repelling ISIS and other fascist militia.

“Being there, I heard constant updates. One day the Jihadis would get closer. The next they were pushed back,” he says.

Sami ultimately left Rojava because he didn't want to join the fighting. His escape was challenging. “I tried two or three times. It was about 4 a.m. and dark when I went with a smuggler to the border. He cut the barbed wire and fixed it so the soldiers would not know. I walked alone for 40 minutes to a village, took the mini-bus to Cizre and flew back to Istanbul,” he says.

Making Istanbul home

Sami reminisces warmly of his first years in Istanbul. He was involved in supporting other refugees in a soup kitchen, there was a strong international network, and he fell in love with a British woman.

A dominant Western narrative suggests most refugees want to get to Europe. Sami contradicts this story, as do UN figures on displacement: 65 million people were officially displaced in 2016, 40 million are in their country of origin, and only 2.3 million travelled to the West.

Although Sami is fleeing persecution, he would not be considered in these official figures, like many others. In late May 2013, Sami along with many of his friends, he joined Occupy Gezi, the protests to protect an urban green space from destruction.

“I was so angry about Syria,” he reflects. “I went to Gezi everyday, as I did not have the chance to do much [protesting] in Syria.”

Post-coup Turkey

The Turkish state has long persecuted Kurds, but it was not until after the failed 2016 coup that Sami felt truly unsafe. The Syrian consulate refused to renew his passport. So Sami risked living undocumented; his visa relied on a valid Syrian passport. The authorities forced two of his undocumented Syrian friends to camps near the Syrian border.

“You cannot really call it a camp," he says. "Conditions are hard. You cannot eat. There are thousands of people with 20 toilets, and no doctors.”

Kurds were also targeted on the Turkish streets by fascist gangs, emboldened by the Erdogan regime's increased tactics of authoritarianism. With time running out on his passport, Sami married his girlfriend and left to Europe on a family visa.

Safe, not settled

Compared to many Syrians, Sami considers himself fortunate. He resides in Germany, living under European law, thanks to his family which could afford, and enable, his escape from Syrian prison. But after surviving Assad, Sami now must contend with racism in the North.

"For the first time in a long time I feel safe. But I did not come here to have a better life, or to become European. I have been forced to leave my country. I have been also forced to leave Turkey.”

Oil-driven crises

The West, of course, played a key role helping to foment the chaos of the Middle East. It supported dictators. It led the war into Iraq, which created ISIS and enflamed the civil war in Syria. In their quest for oil, major Western powers along with Russia have taken sides in Syria, which has become a proxy war for continued oil dominance.

The West has also been lukewarm in its support for Rojava, which is where the real democratic revolution is taking place. At the same time, Turkey remains a Western ally despite its tacit support of ISIS against the Kurds, and at home it continues to commit war crimes against its large Kurdish diaspora.

Thinking back to where it all started, Sami says, “The revolution began as a peaceful civilian movement for all Syrians, Kurds, Arabs, everyone. And I look at where we are now and it is so depressing. The revolution has been stolen.”

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments