Great mysteries need a key to solve them. The Earth going around the sun, rather than vice versa, took Copernicus to screw the Church's head on straight though it almost cost him his own. Radioactive material that scientists could actually work with took Marie Curie sifting tons of pitch blend; but she did it. Then we got atomic energy and, of course, the atomic bomb.

Climate change awaits its Copernicus. Its Curie. Or does it? We've got Al Gore and James Hanson and Bill McKibben, all of whom have led the charge. And a younger, more probable aspirant has appeared, a geologist named Jason Box. But maybe the mystery of climate change is so grand it defies the puniness of man. Maybe the key sought to solve it, if solution is even the right word, is not a person, not even a team. But rather a place. One where the complexities of Biblical scale change play out at a safe distance (at first), yet can keep us riveted to our gadgets and feed our human hunger for the kind of tragedy voyeurism we seem to love. And be addicted to. The place should allow us a clear window, ever present, with a long time frame so we become attached and have time to respond. Or think about responding.

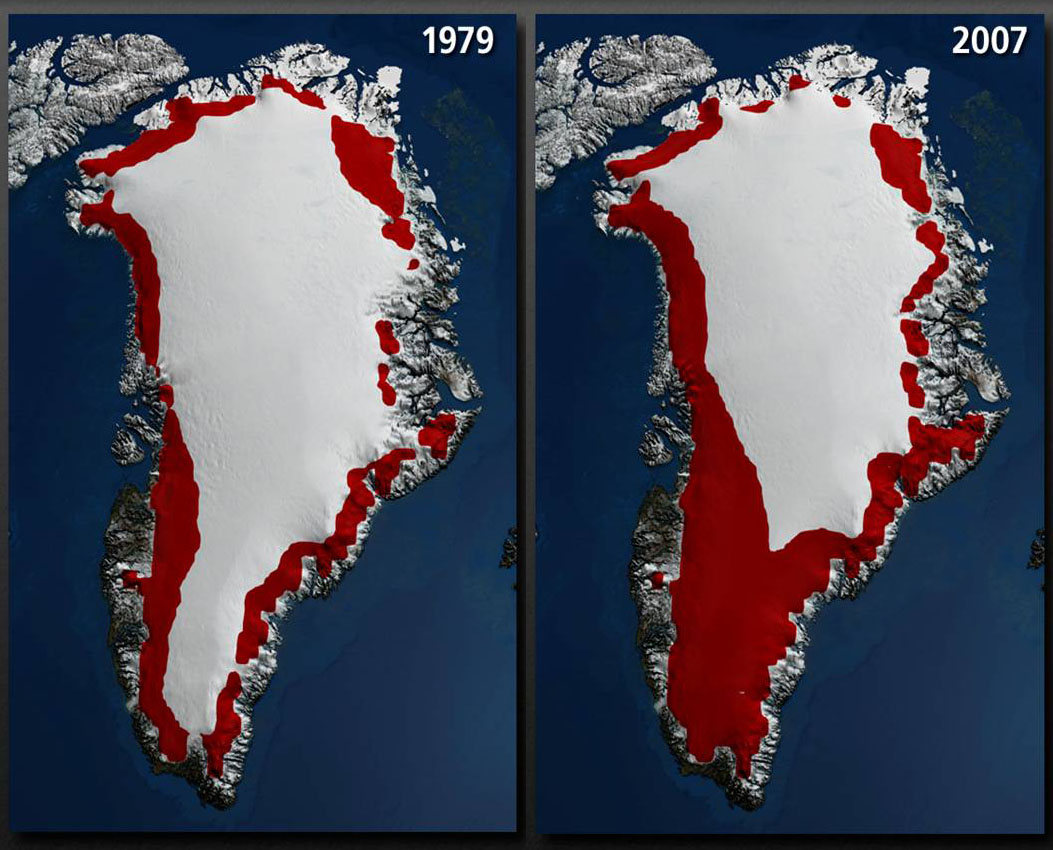

That place, of course, is here now. It has teams scrambling all over its surfaces, one of which is led by Box for his dark snow project. It's Greenland, the largest island on our planet, one gowned in white ice like some frozen princess out of time awaiting the right kiss of sun and weather to awake, and in the words of the great mythologist, Mircea Eliade, to reveal to us "a myth of the destruction of the world, followed by a new Creation and the establishment of the Golden Age."

Now, that would be something to look forward to.

A bit much, you say? A wacky fantasy? Maybe. But the scenes now playing out in Greenland's de-icing are like nothing we've ever witnessed before. This isn't Hollywood. This is a strange, white, icy wonderland reality in a new millennium, and like some wild natural opera/symphony that you'll be able to hear, see and even feel, Greenland is like Beethoven on steroids. A crazy man putting a wild bee in your ear, then rattling your head so you finally start to think.

Who knows? Maybe Greenland undressed will show us we lived on a poorer planet in cooler weather the last few thousand years. Or maybe not. Maybe it will show us we lived in a world rich beyond our ability to comprehend. So we trashed it. For the near term, though, as a key, as a window, it can help reveal a new world we desperately need to know so much more about than we do now. In a way, the fact that Greenland can literally strip is very with-it in a sex-obsessed world. Who knows what’s going to pop up?

Now all we see is ice. Mostly ice melting. But beneath the ice is an inhabitable world. A place. A place ringed with mountains, ribboned with rivers. anchored by earth, minerals, lakes waiting to fill with water, and who knows what else? The scale and prospects are breathtaking. And scale, as they say, changes everything.

Take the Petermann Glacier.

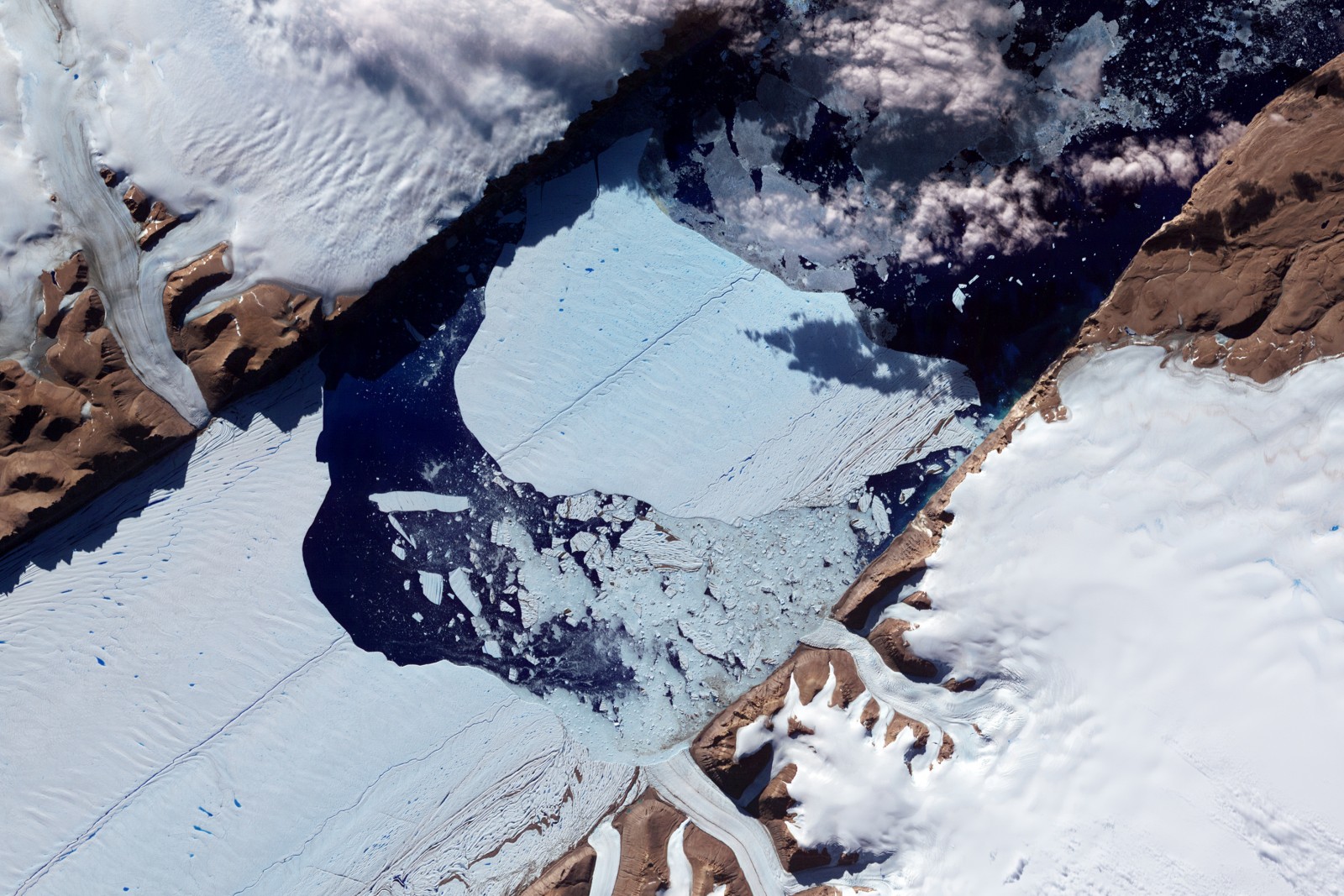

As natural phenomena go glaciers are grand and suggestive. They grow and shrink, they move, they glitter and weep, they calve little icebergs that float off, never to return. The Petermann Glacier has something called an ice tongue. It's about 40 miles long and ten miles wide. Like two hundred or so glaciers in Greenland, this one's headed to the sea. But to get there, part of the tongue has to break off and drift into the Arctic Ocean, Baffin Bay or the North Atlantic.

In 2010 the Petermann Glacier's tongue broke, calved that is, as a 100 square mile chunk, 2000 feet thick at the rear and a couple hundred feet thick at the tip. It drifted south towards Iceberg Alley off Newfoundland. Melting as it moved, attracting schools of Humpback whales, ruining many a lazy tourist boat captain's summer, folks from everywhere dying to get close to see all the beautiful ice encircled by whales. Meanwhile, back at the Petermann Glacier, the slow crawl of the ice to the sea accelerated. Last summer it calved again, sending a bigger ice tongue south than two years earlier.

Now we're talking, in the language of entertainment voyeurism, a Manhattan-Sized iceberg. Two Manhattans maybe. Depends how far south the ice is before you see it as it's always melting. Disappearing.

We know all this courtesy of satellites, scanners, ice-core drillers and scientists. The imagery also has identified a canyon possible gouged by the Petermann glacier. It is 400 miles long and beneath layers of the princess's gown older than human time. That is mythic. But the hidden canyon needs a better name than the ham-handed Greenland's Grand Canyon, which you see tossed around.

I wonder what the Inuits who first came there around 4,500 BC called Greenland. Primitive peoples shaped prehistory here. Norsemen, the Vikings, who came much later, had their own big bloody, life-changing myths fired by mead, rape and pillage. Ones that shaped their world anew. They worshiped them and pissed on the cross.

It seems to me that climate change is dying for a big myth that isn't going to make you want to slit your wrists. Greenland fits the bill. We don't do it, the place will manifest its mythical status anyhow. Like it gives a damn about what we think. Myths are more powerful than we ever thought of being, hedge funders down to oligarchs down to you and me.

A couple things to corroborate that.

If you got in my car with me at my house on the Quebec border in Vermont, and we drove 20 or so hours northeast through the boreal forest and over the high escarpment of Quebec to Labrador City, turned around and came back by my place, but kept going down the eastern seaboard, all the way to St Petersburg, Florida; there you have it, an end to end run of Greenland's circumference.

Then there's Erik the Red. He never saw the Petermann Glacier, but the way he lived certainly touches on myth, especially Norse myth with its long boats, bloody sagas and warrior's sense of humor. As the legend goes Erik was banished from his home in Iceland for killing a man. Taking his serfs, family and hangers on, he sailed west in open long boats like a Viking Columbus. Smack into Greenland. Settled on the inhabitable shore, glacier tongues to the north and glacier tongues to the south, after three years he sent word back to Iceland about discovering a green land. Come on over!

One wonders what the takers thought once they arrived. Be that as it may Erik's son Leif Ericsson, around 1000 AD, sailed 800 miles further west, establishing the first Norse settlement in North America on the Great Northern peninsula of what is now Newfoundland. Whether from fights with the Innu natives or disease or something else, history that old being murky, Leif and his band returned home.

And who, we ask now, will populate the Greenland of the melting princess, fill the single clear window we have on climate change? Who will they be and what might they do?

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments