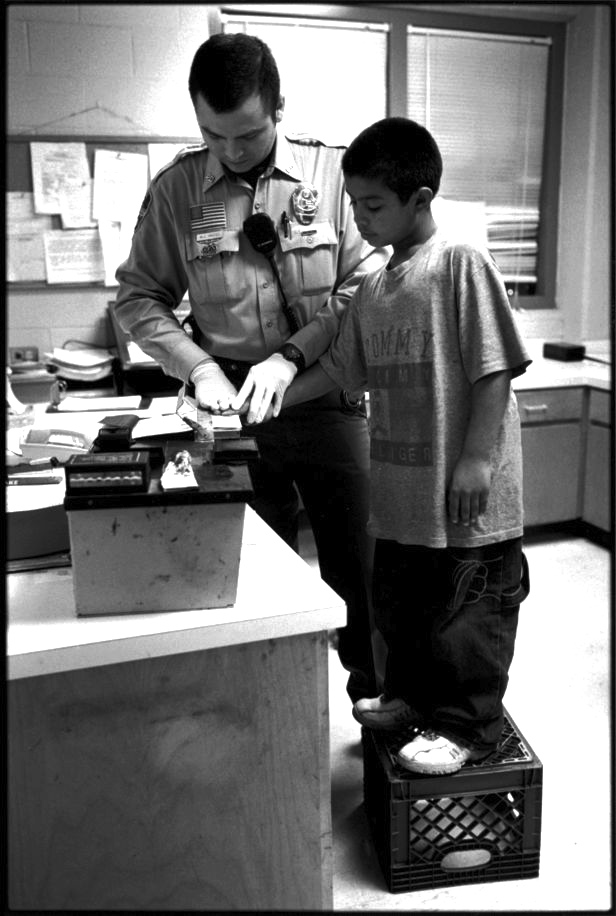

Ashley Brown, a Dallas high school sophomore, missed four days of school after her grandmother died. Shortly after that, a teacher taking roll missed the short-statured student and accidentally marked Brown absent. Then Brown missed school because she was suspended for an altercation. She missed another day when she was suspended for being late to class, because she was in the restroom.

The next thing she knew, the county truancy court summoned her. She owed mounting fines. "I was very worried because my family cannot pay those types of tickets," Brown, 16, said in an interview. "I'm on the honor roll. I'm academically prepared. For them to penalize me because of these mistakes — wow."

Brown is one of 36,000 Dallas students who have faced truancy cases in the last year. In 2012, Texas adult courts prosecuted 113,000 truancy cases, more than twice the number pursued in the other 49 states combined.

That statistic, and the penalties children and parents face because of Dallas County's Truancy Court, is why three law centers — Texas Appleseed, Disability Rights Texas, and the National Center for Youth Law — are filing a federal complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice Wednesday on behalf of seven children. They're protesting a system that they allege is built on the incentive of drawing more and more money — and students — into the courts, violating the Constitution, the Equal Education Opportunities Act of 1974, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Civil Rights Act.

"Dallas truancy courts have a very punitive culture," said Deborah Fowler, Texas Appleseed's director. 'Kids as young as 13 are being arrested, threatened to be put in jail."

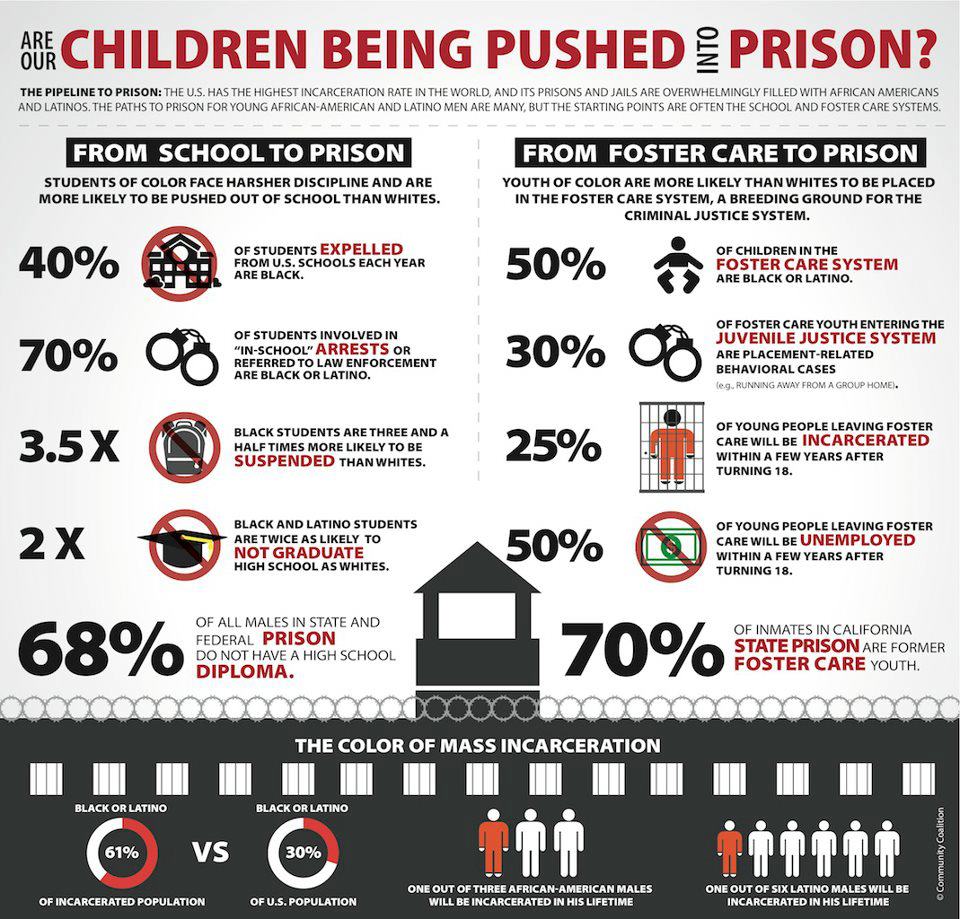

School discipline, and the effects of zero-tolerance policies, have been a top priority for states and school districts across the country as state legislatures seek to arm up in the wake of the Newtown elementary school shooting in December. That push comes amid an ongoing battle against what advocates call the "school-to-prison pipeline," in which students who violate minor rules wind up in court. Research has shown that minority students receive disproportionate school punishments.Roddi Schoneberg, a Dallas preschool teacher, appeared before a judge because her three children, two of whom are on the autism spectrum, were late to school too many times.

She was fined $600, and has since lived with nightmares of possible arrest. "I quit my job," she said. "I'd become a criminal of the state of Texas." She said she knows of two single parents who have dealt with the same problems. One was arrested. In her own family, the process has made her children — Gracie, Gabe and Rosie — hate school. "They cried every time I made one of my payments, worried that I would go to jail."

"This is what I thought Soviet Russia was in the sixth grade," Schoneberg said.

In New York, a task force known as the School-Justice Partnership comprised of former New York Chief Judge Judith Kaye and representatives from the NAACP recently released a report asking for the city to establish an inter-agency initiative to reduce suspensions. Activists in Los Angeles have succeeded in making penalties for being late to school less punitive and expensive.

Meridian, Miss., recently resolved a federal case similar to the Dallas complaint. After an investigation found that in Meridian, black students were five times more likely than their peers to be suspended, the district and the government reached an agreement for Meridian to come into compliance with non-discrimination law by 2017.

Texas in particular has been known for its zero-tolerance school policies. A 2001 study reported that 31 percent of students there were suspended or expelled in secondary school, four times each on average, and linked the discipline with lower academic performance.

The Dallas complaint outlines the cases of seven students in the county's four school districts. One student, identified as B.B., says she was absent because the school didn't provide her with "necessary special education services," the complainant says. J.D. missed school because of a chronic respiratory disability. K.W., got stuck in the truancy system because she was tending to her mother, who had heart disease. S.M. missed school because she had medical complications after giving birth. I.J. got a court summons because she was late to class — for using the restroom. And L.P. is on the books because she was sick, and her legal guardian didn't call the school to tell them.

In Texas, students who miss three days of school in four weeks, or 10 days of school within six months, can be charged with failure to attend school. This offense is a Class C misdemeanor under the state Education Code, or a juvenile offense under Family Code. The Texas legislature signed off on a special truancy court for students in Dallas about a decade ago. At the time, the goal was to address cases in a timely manner. The court prosecutes children in these courts, subjecting students as young as 12 to "an adult criminal court process," according to the complaint. Because these children have no attorneys, the complaint alleges, "these children are almost guaranteed a criminal conviction."

Convicted students can be handcuffed and imprisoned. Their parents can be charged, and often miss work days to attend court hearings. The complaint alleges that students are often "coerced and cajoled into pleading 'guilty,' even when they have valid excuses for school absences." Children who miss court, the complaint says, are arrested at school. Three-quarters of the court system is financed by the fines, which "creates an incentive to make sure you have a high volume of cases," the complaint says.

"We were so alarmed with what we saw," said Fowler, who saw arrests and court appearances firsthand in her investigation. "Because they created a specialized system, there's a tendency to feed the system."

The complaint asks the Department of Justice to require schools to use court as a last resort after a long process of school-based interventions. The complainants ask that schools be more flexible about accommodating students for "sound reasons for tardiness or truancy;" that they take disabilities into account and that they provide positive behavioral supports.

Calls to the Dallas school district and truancy court were not immediately returned.

The truancy court often boasts that 90 percent of students who go through the system graduate from high school. But, Fowler said that statistic only includes students who were eligible to graduate the year they are entered into the system and "only students who are motivated enough to appear in court." In 2012, only 41 percent of students charged with truancy appeared for their first hearing.

The court system's pervasive influence may distance students from learning.

"I used to love coming to school and getting an education," Ashley Brown said. "But now it's like my school is more of a prison to me."

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments