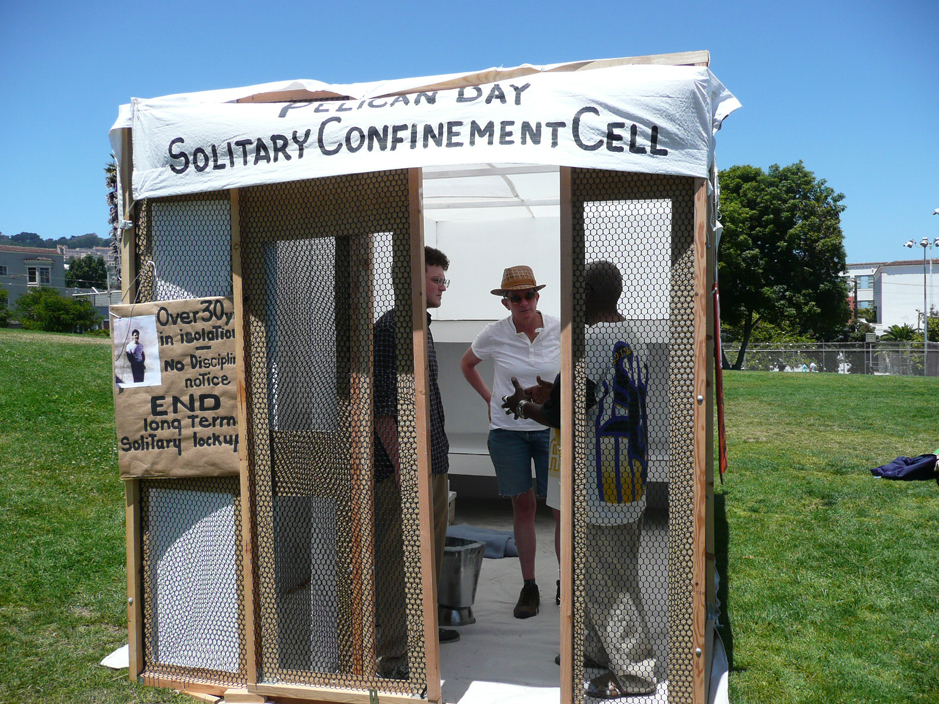

Shortly after two statewide hunger strikes rocked the California prison system in 2011, I began corresponding with several of the men who had participated in the protests. They were mostly alleged prison gang members who have been sentenced to indefinite terms in California's Secure Housing Units, known as SHUs. They spend 22.5 hours of every day in 7 by 11ft windowless cells. If they're lucky, the remaining 1.5 hours are spent alone in a barren exercise yard with 15 foot high concrete walls and a covered ceiling that prevents them from catching a proper glimpse of the sky.

They are allowed no phone calls, no contact visits with loved ones and their only physical interactions with fellow humans is when they are handcuffed or strip searched by guards. The worst part of this intolerable existence, they say, is that because of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR)'s gang policy, once a prisoner is sent to the SHU, it's next to impossible for him to get out again. One of my correspondents, Patrick, explained his motivation for going on hunger strike:

"I have been in the SHU for 14 years, I've been in the short corridor here since its opening. I am validated (as a gang member) and have an indefinite SHU term. I have a life sentence. If the gang policy doesn't change, I will die in this unit. I am 41 years old."

The first two hunger strikes both eventually ended after approximately three weeks when the CDCR agreed to make some changes to the policies that keep men like Patrick in the SHU for decades. Two years later, however, it seems that little meaningful reform has taken place and so, on 8 July, nearly 30,000 prisoners across the state began a third hunger strike, which may end up being the largest and longest in California's history.

Despite the gravity of the situation and the prisoners' evident desperation, so far the CDCR has shown little willingness to cede any ground.

At the heart of the protest is the CDCR's policy of taking validated gang members and associates out of the mainline prison population and handing them a one way ticket to the SHU. This policy was borne out of an effort to curb gang control of prison yards and to keep other inmates safe from violence.

There is no external review of the validation process, however, and many prisoners, and their legal representatives, claim to have been falsely validated on flimsy evidence such as possessing the wrong kind of book or the wrong kind of tattoo or simply greeting a known gang member. The CDCR's own former under-secretary, Scott Kernan, (who retired after the first two hunger strikes), admitted in an interview that the department was guilty of "over-validating" inmates, and that their SHU policies had "gone too far". Yet, once a validated prisoner ends up in the SHU, his only way out is to become a state informant debrief), or in prison parlance, to snitch on other inmates.

This is something of a non-option for SHU prisoners who have no valuable information to offer the authorities in exchange for their release. It's also a non-option for most gang members who do happen to have valuable information, because becoming an informant will almost certainly put their lives and the lives of innocent family members in serious danger. So SHU prisoners who may have long since dropped any gang affiliations and simply want to serve out their time are faced with an impossible choice: debrief and risk death, don't debrief and remain buried alive.

I raised this Catch-22 with Pelican Bay's Warden Greg Lewis when I visited the prison's notorious SHU last year. Lewis acknowledged the dangers associated with debriefing but said, "the men who choose to debrief tend to recognize that they put their families at risk by joining the gang in the first place". A fair point, I suppose, but hardly a constructive one. Lewis also emphasized that debriefing was a vital component of the prison's overall gang management strategy and would remain so, regardless of that risk.

After the first round of hunger strikes, the CDCR did make some concessions to prisoners, however, promising to use new criteria for placing inmates in the SHU and to institute a step down program that would allow inmates an opportunity to get out of isolation that didn't necessarily involve debriefing. Since these changes were implemented, vorrections officials say they have reviewed nearly 400 cases and around half of those have been returned to the general population. That is welcome news for those lucky few but has had no impact on the vast majority of long term SHU inmates.

According to Alexis Agathocleous of the Center for Constitutional Reform, which has filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of prisoners at Pelican Bay "not a single one of our clients has experienced any change in their situation whatsoever". Even more disturbing is the fact noted by Shane Bauer in the Los Angeles Times recently, that in the past year, despite the reforms (or possibly because of them) the overall SHU population has actually increased by 15% to a total of 4,257 statewide.

Little has changed then for the men who remain trapped in what they describe as living graves and so they have resorted once again to the only means of protest available to them. As of Monday, day 8 of hunger strike number three, thousands of prisoners were still refusing meals. One of the strike's organizers, Todd Ashker, who has been locked in a cell in the Pelican Bay SHU since 1990, declared at the outset that "this time there's a core group of us committed to taking this all the way to the death if necessary".

It remains to be seen if the CDCR will let that happen, but it seems that unless they embark on meaningful change to their long term isolation policies, things could start to get ugly.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments