Debbie Bourne, 45, was at her apartment in the Liberty Village housing projects in Plainfield, N.J., on the afternoon of April 30 when police banged on the door and pushed their way inside. The officers ordered her, her daughter, 14, and her son, 22, who suffers from autism, to sit down and not move and then began ransacking the home. Bourne’s husband, from whom she was estranged and who was in the process of moving out, was the target of the police, who suspected him of dealing cocaine. As it turned out, the raid would cast a deep shadow over the lives of three innocents—Bourne and her children.

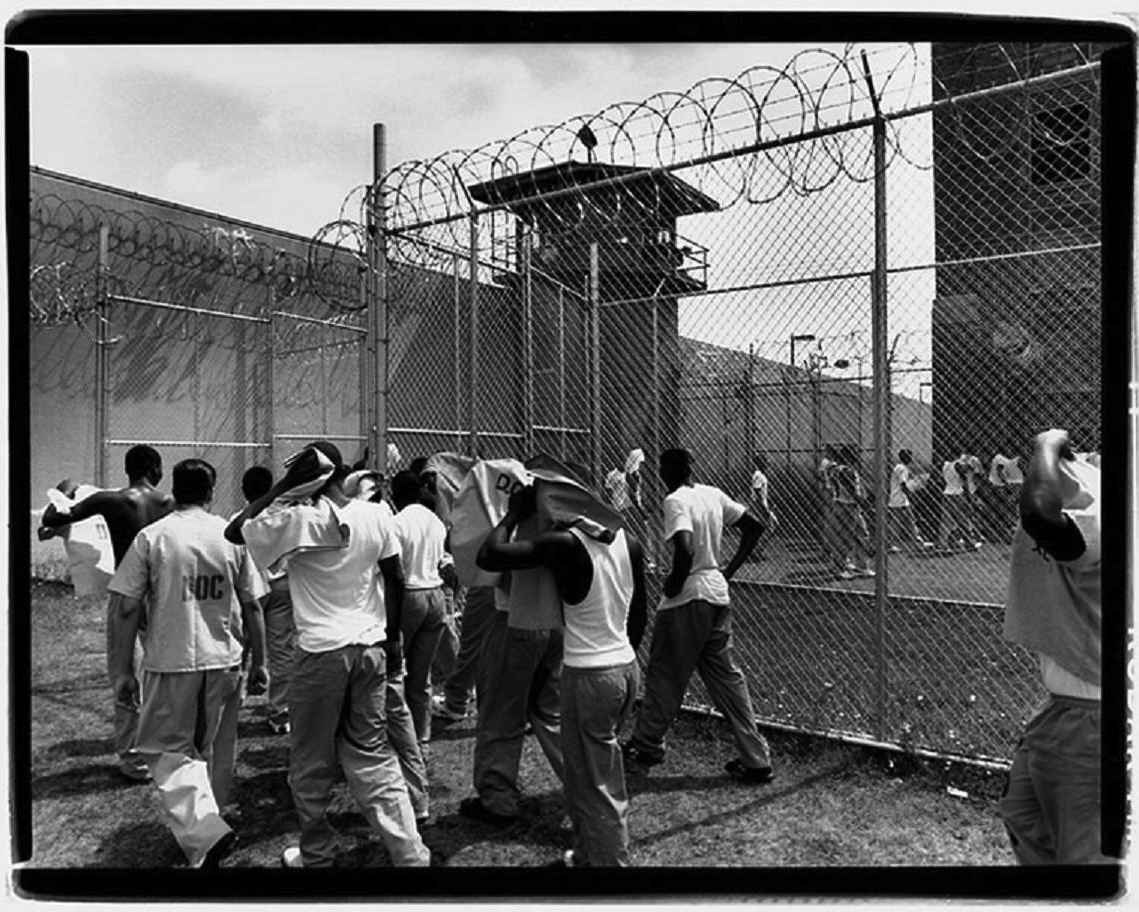

The murder of a teenage boy by an armed vigilante, George Zimmerman, is only one crime set within a legal and penal system that has criminalized poverty. Poor people, especially those of color, are worth nothing to corporations and private contractors if they are on the street. In jails and prisons, however, they each can generate corporate revenues of $30,000 to $40,000 a year. This use of the bodies of the poor to make money for corporations fuels the system of neoslavery that defines our prison system.

Prisoners often work inside jails and prisons for nothing or at most earn a dollar an hour. The court system has been gutted to deny the poor adequate legal representation. Draconian drug laws send nonviolent offenders to jail for staggering periods of time. Our prisons routinely use solitary confinement, forms of humiliation and physical abuse to keep prisoners broken and compliant, methods that international human rights organizations have long defined as torture. Individuals and corporations that profit from prisons in the United States perpetuate a form of neoslavery.

The ongoing hunger strike by inmates in the California prison system is a slave revolt, one that we must encourage and support. The fate of the poor under our corporate state will, if we remain indifferent and passive, become our own fate. This is why on Wednesday I will join prison rights activists, including Cornel West and Michael Moore, in a one-day fast in solidarity with the hunger strike in the California prison system.

In poor communities where there are few jobs, little or no vocational training, a dearth of educational opportunities and a lack of support structures there are, by design, high rates of recidivism—the engine of the prison-industrial complex. There are tens of millions of poor people for whom this country is nothing more than a vast, extended penal colony. Gun possession is largely criminalized for poor people of color while vigilante thugs, nearly always white, swagger through communities with loaded weapons. There will never be serious gun control in the United States. Most white people know what their race has done to black people for centuries. They know that those trapped today in urban ghettos, what Malcolm X called our internal colonies, endure neglect, poverty, violence and deprivation. Most whites are terrified that African-Americans will one day attempt to defend themselves or seek vengeance. Scratch the surface of survivalist groups and you uncover frightened white supremacists.

The failure on the part of the white liberal class to decry the exploding mass incarceration of the poor, and especially of African-Americans, means that as our empire deteriorates more and more whites will end up in prison alongside those we have condemned because of our indifference. And the mounting abuse of the poor is fueling an inchoate rage that will eventually lead to civil unrest.

“Again I say that each and every Negro, during the last 300 years, possesses from that heritage a greater burden of hate for America than they themselves know,” Richard Wright wrote. “Perhaps it is well that Negroes try to be as unintellectual as possible, for if they ever started really thinking about what happened to them they’d go wild. And perhaps that is the secret of whites who want to believe that Negroes have no memory; for if they thought that Negroes remembered they would start out to shoot them all in sheer self-defense.”

The United States has spent $300 billion since 1980 to expand its prison system. We imprison 2.2 million people, 25 percent of the world’s prison population. For every 100,000 adults in this country there are 742 behind bars. Five million are on parole. Only 30 to 40 percent are white.

The intrusion of corporations and private contractors into the prison system is a legacy of the Clinton administration. President Bill Clinton’s omnibus crime bill provided $30 billion to expand the prison system, including $10 billion to build prisons. The bill expanded from two to 58 the number of federal crimes for which the death penalty can be administered. It eliminated a ban on the execution of the mentally impaired. The bill gave us the “three-strikes” laws that mandate life sentences for anyone convicted of three “violent” felonies. It set up the tracking of sex offenders. It allowed the courts to try children as young as 13 as adults. It created special courts to deport noncitizens alleged to be “engaged in terrorist activity” and authorized the use of secret evidence. The prison population under Clinton swelled from 1.4 million to 2 million.

Incarceration has become a very lucrative business for an array of private contractors, most of whom send lobbyists to Washington to make sure the laws and legislation continue to funnel a steady supply of poor people into the prison complex. These private contractors, taking public money, build the prisons, provide food service, hire guards and run and administer detention facilities. It is imperative to their profits that there be a steady supply of new bodies.

Bourne has worked for 13 years as a locker room assistant in the Plainfield school system. She works five hours a day. She does not have medical benefits. She struggles to take care of a daughter in fragile health and a disabled son.

Bourne and her children sat terrified that April afternoon in their apartment. After about 10 minutes four more police officers arrived with her husband. His clothes were torn and disheveled. His face was swollen and bruised. He was handcuffed. “He looked like he been beat up,” she said.

“They were telling him, tell us where you have the stuff at, the drugs at,” Bourne said when we met at a prison support group I help run at the Second Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, N.J. “Tell us where you have the stuff at ’cause if you don’t we are going to handcuff her and the kids. And you be a man, you know, you know be a man and tell so we ... don’t have to handcuff her and the kids. And he told them they [she and the children] have nothing to do with this, and there’s nothing in the house.”

The police took her husband to the kitchen. “They were hittin’ him in the kitchen,” she said, “punchin’ him, like in the stomach. Like by his ribs. He was saying they don’t have nothin’ to do with it, you know, they don’t.”

She could hear the officers repeating: “Where are the drugs?” They beat him for about 10 minutes, she said. The police then went into the living room and handcuffed Bourne and her son and daughter. They took her husband out of the apartment. Three officers remained until a K-9 dog unit arrived. The police removed the handcuffs and took Bourne and her children into the kitchen. A dog was guided around the living room and then coaxed up the stairs to the bedrooms, where it stayed for five minutes before being brought back down. The police remained in the bedrooms about 30 minutes.

Bourne heard banging sounds. She heard one of the officers say: “We found drugs in a black boot.” Her husband’s boots had been in a plastic bag with his clothes in preparation for his moving out of the apartment.

Although not under arrest, Bourne was taken to the police station, where she filled out forms and was fingerprinted. No charge was filed against her at the time. Two hours later the police drove her home. It would be weeks before Bourne learned—in an indirect way—that she, too, would face the possibility of jail time because of the raid.

When Bourne returned home that spring night, “It looked like a tornado had went through my bedroom. Everything was piled on top of each other. The TV was broken. It had been pushed over on the floor. I had my cellular phone charging in the socket—the charger was ripped out the socket. There were nails holes [made by the police] in the wall. You could see little dots, probably about six, seven, 10. The computer was pushed over on the ground. The cable was pull out the TV. The blinds was removed. The shades were removed from the windows. The containers that I have clothes in was all thrown on the bed. The dresser drawers were sitting high on top the bed.”

“I felt violated,” she said. “Very violated. I felt that if [they] wanted him so bad, why destroy my stuff?”

In cleaning up she found that her wedding and engagement rings, kept on the top of her dresser in a small box from Macy’s, had disappeared. She soon found that other items were missing.

“They took video games that I bought for my kids that was packaged inside a closet in a shoe box,” Bourne said. “They took a remote control that go with one of the game systems. I had collectible like coins that I bought way back. That was gone.”

She had seen police leaving the apartment with a yellow plastic container that had a new Acer computer she had bought for her cousin. “I had told them, ‘Where are you going with that computer?’ ” she said. The police immediately returned it.

Her husband is in Union County Jail in Elizabeth. He is charged with possession of drugs in public housing and possession of drugs in a school zone. When Bourne spoke to him by phone he told her the police had taken $900 he had in his pocket and that he had $2,000 in the apartment closet. When she checked the closet the money was not there. The police report in Bourne’s possession claims the officers confiscated $134 from the apartment and $734 from her husband. There was no mention of the other missing items, including her rings.

When Bourne was in court for her husband’s arraignment in early July she was stunned to hear the prosecutor tell the court that cocaine was also found by the police in a pocket of her jeans.

She told me she was not wearing jeans at the time. She said she does not take or sell drugs. And she pointed out that the police report, which she showed to me, never mentioned finding drugs on her person. After being charged she met with a public defender who told her that she should urge her husband to confess that the cocaine was his. If he does not, Bourne could face six years in jail.

The state-appointed attorney, with whom Bourne spent less than 15 minutes, told her to stay out of trouble. She has never been arrested at any time in her life. She said the encounter with the lawyer left her feeling “degraded.”

“I have two kids,” she said. “I’m 45. Why would I be trying to go to jail? That’s not me, that’s not how I was brought up. My daughter is sick. My son has a disability. I’m the only one that take care of both of them.”

If she goes to jail it will be catastrophic for her children. But this is not a new story. It happens to families every day in our gulag state. Bourne is one human being among hundreds of thousands routinely sacrificed for corporate greed. Her tragedy is of no concern to private contractors or supine judges and elected officials. They do not work for her. They do not work for us. They are corporate employees. And they know something Bourne is just discovering: Incarceration in America is a business.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments