It’s been 16 straight days of protests in the San Francisco Bay Area, during which activists have filled the streets demanding justice for Eric Garner, Michael Brown and the many other black men killed by police officers nationwide. Businesses have been vandalized, ATMs smashed and people injured, including peaceful protesters who tried to intervene in the looting that has occasionally accompanied the rallies.

The anger and frustration at a policing system protesters rightly describe as discriminatory has become palpable. But now comes the hard part: Can the anti-police brutality movement go beyond rhetoric and offer concrete ideas that result in new policies and legislation?

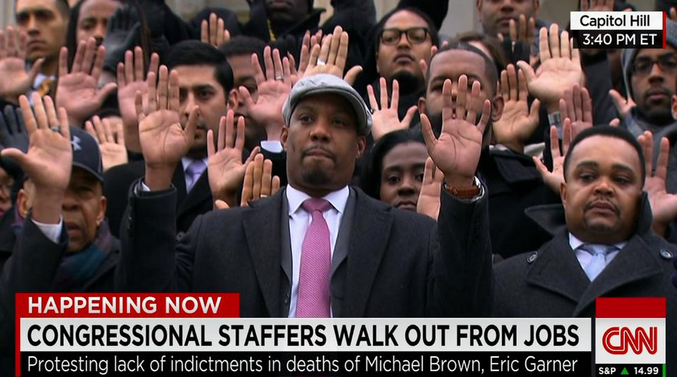

A National Day of Anger has been scheduled for Saturday, Dec. 13, in New York City and Washington, DC, with similar protests planned throughout the country, organized by coalitions of rising leaders.

“We want people to shut down their cities for justice,” said Synead Nichols, a lead organizer with the Millions March, in a statement posted on the group’s site. “We are continuing where the freedom fighters of the Civil Rights Movement left of…(and) are a new generation of young multiracial activists willing to take up the torch and we’re not going to stand for this anymore.”

Dozens of groups have sprung up in the months following the death of Michael Brown, including Ferguson Action, Black Lives Matter and Mobilizing Our Voices Everywhere (MOVE). Some have issued a list of demands, ranging from ending all forms of discrimination to “the full employment of our people” and decent housing. Others include freedom from mass incarceration and an end to the schools to prison pipeline.”

These are all fair demands, but they are vague and unlikely to result in real changes. Why? Because blaming everything on racism and discrimination absolves the African-American community and its leaders from taking responsibility for its problems, including black-on-black violence, youth who would rather sell drugs than work, low graduation rates and lack of good role models.

Driving in to work each day, I see homeless black men and women sitting in parks in north Oakland, and young black men standing on corners in the middle of the day. It is entirely possible that I will one day write about their murders, usually over drugs, in my job as a local reporter. So far this year, Oakland has recorded 80 homicides, most of them young black men killed by other black men.

This violence is something the black community has not always been willing to address — least of all at a moment as tense as the current one, where passions have reached a pitch over white men murdering black men with impunity. At a recent event discussing solutions to police brutality, I raised a question about the role of personal responsibility among black men and many bristled at the question.

“Black folks are not breaking the law at any more disproportionate rates than whites, but they are much more likely to be punished for it,” said Zach Murray, a 25-year-old Oakland resident, echoing the sentiment of many of his peers. "People's identities have been marked as illegal."

Murray, a Cornell University graduate, recounted a story about struggling with his bike lock and having police arrive after someone reported an "attempted bike theft."

"It doesn't matter where you went to school or what you are wearing," he said. "To many people, you're still a nigger."

There is evidence of disproportionate punishment when it comes to drugs, with a recent ACLU study showing blacks are arrested for marijuana possession nearly four times more often than whites, despite using the drug at the same rates.

But the prejudice is less clear for other crimes. According to FBI statistics, blacks are arrested for 50 percent of all murders and 56 percent of robberies, but make up just 13 percent of the population. Are blacks punished for crimes committed by others? Hardly. While the reasons people commit crimes are complex, it can’t be denied that blacks have higher incidents of “engagement with police” because they break the law more often.

I’m not saying that African-Americans are more “criminally minded.” Far from it. But anyone who works with communities of color can attest that inter-generational incarceration, drug use, teen parents, absentee fathers and the crack epidemic have left black communities demoralized and not at all hopeful about the future.

One of the first stories I worked on at my job was about a 17-year-old girl who had been killed by her brother, then only 14. Both teens were already parents and had not attended school on a regular basis. They were living with their grandmother because their mom was in prison and their father, who also had a lengthy rap sheet, was out of the picture.

Any attempt to reduce encounters with police need to start by dismantling the cycle of apathy, fatalism, low self-esteem, easy access to guns, gangs, prison, broken families, and few job skills that are causing so many young black men to choose violence.

Psychologists have a term to describe the way minorities have assimilated racist attitudes of mainstream culture into their lives, resulting in lower self-esteem: internalized oppression.

Robert Castro, who works with gang members in Oakland through a group called United for Restorative Youth Justice, said that youth involved in crime often target each other because it’s a way of feeling more in control over their lives.

“These kids have no outlets so they take it out on whoever looks like them,” he said. “We see it all the time.”

Clearly, reforms are needed on the police front too, including a reevaluation about how to deescalate situations without resorting to lethal force. Police have a variety of tools, including Tasers, batons, and calling for backup. Instead, they are taught to shoot at center mass and ask questions later. That too must change, and can best be accomplished through meetings between activists and police groups.

There are no easy answers. But given the current crisis that is bubbling over into nationwide strife, now is the time for black leaders—and I’m not just talking about Rev. Al Sharpton—to step up and have an honest conversation about the conditions facing African-Americans in the U.S., without blaming racism for everything. That’s too easy and absolves the black community from engaging in the hard work of telling its youth to shape up, obey the law, stay in school, go to college and pursue interesting work instead of joining gangs or selling dope.

These leaders can come from community organizations or political movements, and they can come from celebrities like Beyonce and LeBron James. Look at the enormous strides made by Michelle Obama when it came to fighting childhood obesity and other initiatives in recent years. There could be many more Obamas who serve as role models and encourage other professional black men and women to become mentors for the younger generation of blacks in America.

Instead of breaking windows and beating up police officers or the reporters who film them when they’re getting violent, protesters need to articulate a clear message of the changes they want to see, while getting real with themselves.

A.B. Chase is a reporter living in the San Francisco Bay Area.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments