The top five countries most affected by threats were all found to be in south-east Asia. Malaysia was the most affected, followed by Brunei and Singapore. Photograph: Romeo Gacad/AFP/Getty Images

More than 1,200 species globally face threats to their survival in more than 90% of their habitat and “will almost certainly face extinction” without conservation intervention, according to new research.

Scientists working with Australia’s University of Queensland and the Wildlife Conservation Society have mapped threats faced by 5,457 species of birds, mammals and amphibians to determine which parts of a species’ habitat range are most affected by known drivers of biodiversity loss.

The project is from the same team of researchers that found just five countries are responsible for 70% of the world’s remaining wilderness.

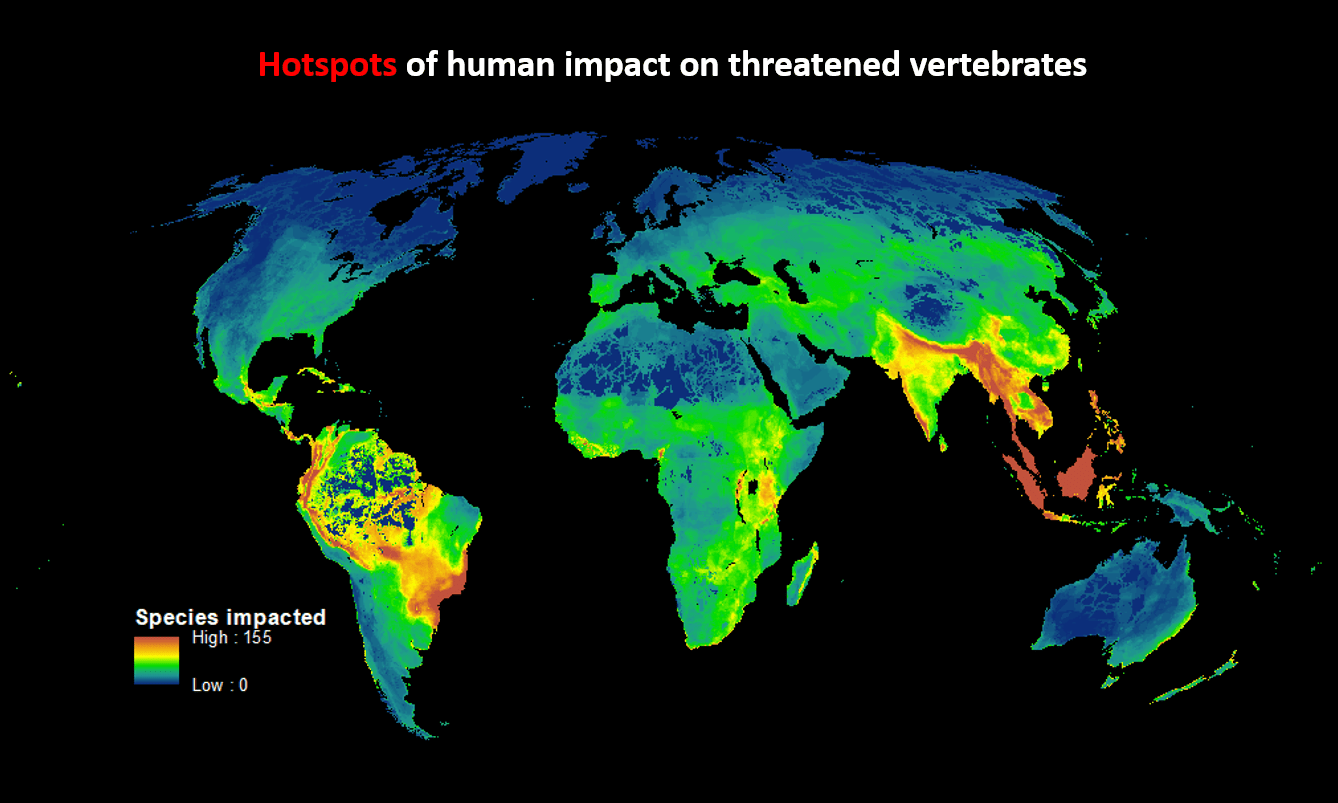

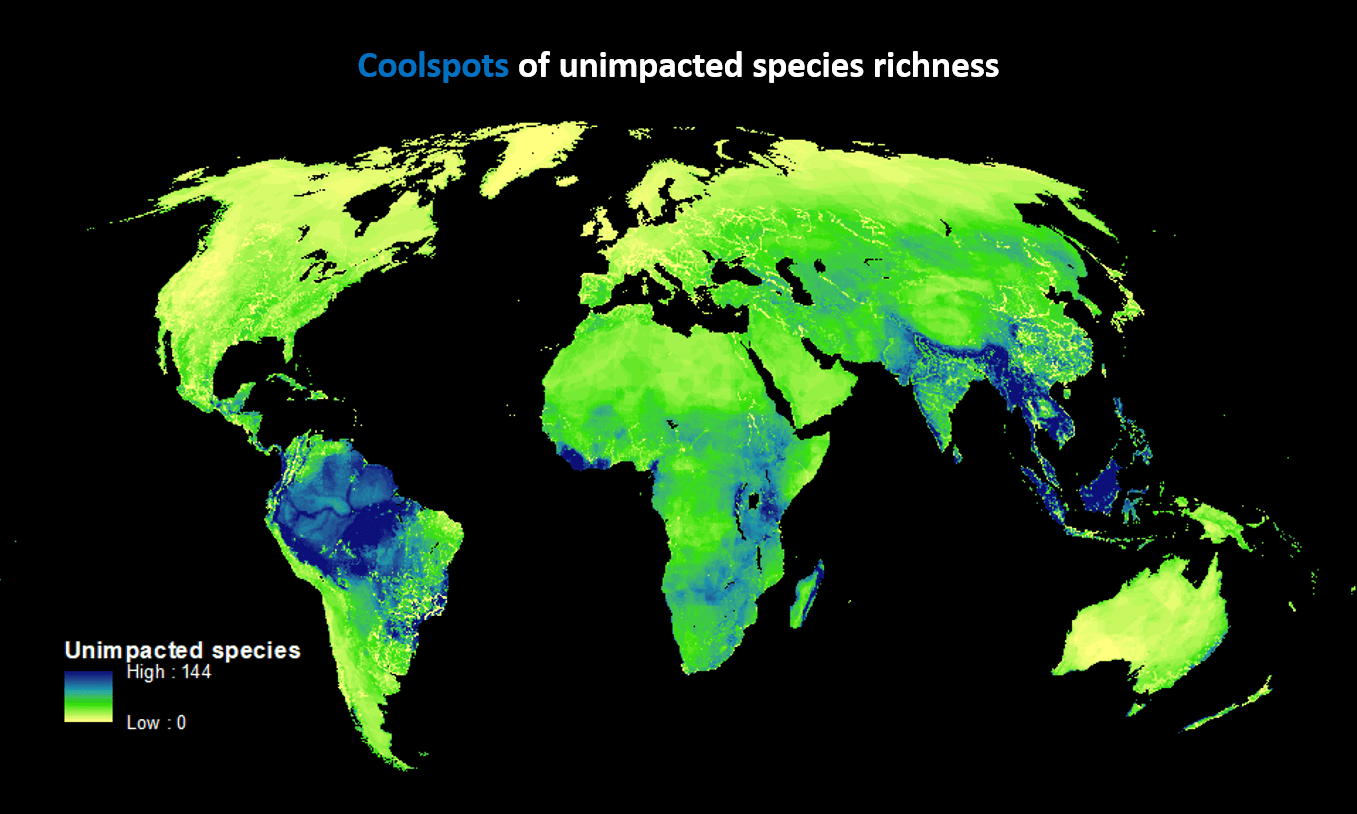

The new research, published in PLOS Biology, maps “hotspots” where species are most affected by threats such as agriculture, urbanisation, night lighting, roads, rail, waterways and population density, and “coolspots” that provide refuge from these threats.

The team looked only at threats that were known to affect a species within its habitat range and found that for the majority of wildlife studied, intrusions were “extensive” across most habitat, “severely limiting the area within which species can survive”.

They said most concerning was their finding that 1,237 species – nearly a quarter of the animals assessed – were affected by threats across more than 90% of their distribution.

The situation was worse for 395 species, or 7%, which were found to be affected by at least one relevant threat across their entire habitat range.

“These results are very alarming and that’s because the threats we’ve mapped are specific to the species,” said James Allan, a University of Queensland post-doctoral researcher and the study’s lead author.

“They’re the primary causes of the species’ decline and the reason they are threatened with extinction. Where a threat overlaps with a species, we know that species will continue to decline.”

Mammals were identified as the most affected group studied, with on average 52% of a species’ distribution degraded by threats.

One in three of the species studied were found to have no exposure to threats across their habitat range, but the researchers cautioned that this result “should be interpreted within the context of threats we consider”.

Two major threats they had not mapped were diseases affecting amphibians and climate change, which threatens all species.

Human impacts were found on species across 84% of the earth’s terrestrial surface.

The top five countries most affected by threats were all in south-east Asia. Malaysia was the most affected, followed by Brunei and Singapore.

The most affected biomes included mangroves, tropical and sub-tropical moist broadleaf forests in southern Brazil, Malaysia and Indonesia, and tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests of India, Myanmar and Thailand.

The countries with the greatest areas of “coolspots” or refuges from threats were also in south-east Asia, as well as the Amazon rainforest, parts of the Andes and Liberia in west Africa.

Allan said that in some cases, hotspots and coolspots were found side by side, which he attributed to the fact there was such a high diversity of species there.

“The obvious thing we need to do is protect the coolspots, the unimpacted areas of species ranges,” he said. “We need to stop threats getting into those areas.

“There’s room for optimism. Every threat that we mapped can be stopped through conservation effort.”

The most affected biomes were in southern Brazil, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Myanmar and Thailand. Photograph: PLOS Biology The countries with the greatest areas of coolspots were also in south-east Asia, as well as the Amazon rainforest, parts of the Andes and Liberia. Photograph: PLOS BiologyOriginally published by The Guardian