On Dec. 8, Canada's newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the start of a process leading to an inquiry on the crisis of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls across the country. The decision was a long time coming, as the previous Conservative government refused to call for any federal investigation – claiming the disappearances and deaths amounted a “police issue” rather than a human rights abomination.

Meanwhile, the Canadian federal police, or RCMP, insisted for years that the vast majority of murdered women were killed by their spouses or other family members. But the claim was shown to be false in a recent investigation by the Toronto Star. The newspaper's investigative team reviewed more than 750 murder cases, some dating back to the 1960s – 224 of which remain unsolved – and found that 44% of victims were killed by acquaintances, strangers and serial killers.

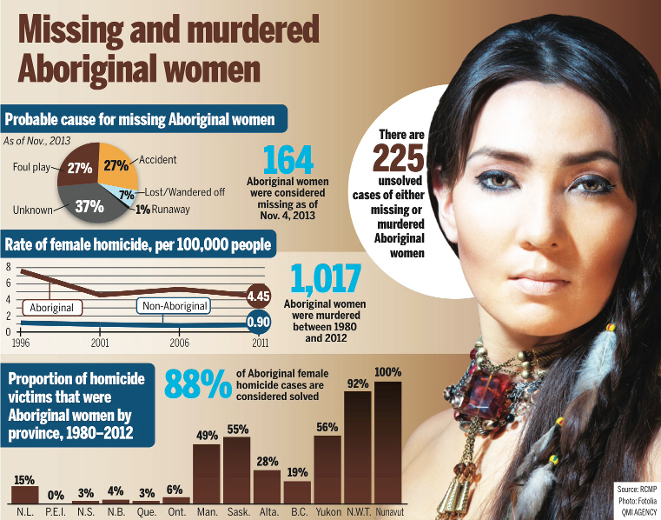

The statistics, covering a 32-year period, reveal that more than 1,200 indigenous women have either been murdered or gone missing. Though First Nations women make up just 4 percent of Canada's female population, 16 percent of women murdered in the country between 1980 and 2012 were indigenous. The Trudeau government’s announcement came as a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was ending its investigation into yet another tragic chapter of the First Nations community: abuse at Christian residential schools.

As explained in the capital’s newspaper, The Ottawa Citizen, “Beginning in the 1880s, more than 150,000 aboriginal children were torn from their families and sent to the schools. They were poorly fed, housed in badly constructed buildings that were often described as fire-traps, and neglected when their health deteriorated..” The last of these schools – which were run by various churches in the interest of “assimilating” native people – was closed in 1996, but the scars left by this history of abuse will likely take generations to heal.

A recent case in Val D’or, a remote mining community of Quebec, showed that while there is hope for conditions changing in the future, in many ways life remains the same for native people. In that instance, eight police officers from the provincial police force have been suspended and stand accused of numerous assaults and abuses of power against aboriginal women in the community.The national French-language broadcaster, Radio Canada, was investigating the disappearance of a native woman named Sindy Ruperthouse when it discovered the many allegations against the officers in Val D’or – demonstrating once again to the Canadian public that the crisis of missing and murdered aboriginal women is ongoing and systemic.

What Radio Canada’s reporters found was not only horrifying but long-running. One woman described what happened to her 20 years before, when she was caught by police drinking a beer on the street. One of the accused took her into an interrogation room at the station. “He pulled down his pants and that was that. After we went back downstairs and it was as if nothing had happened,” she said. The woman was 19 at the time of the assault and was too afraid to report it to higher authorities at the time.

The tragic stories of abuse coming out from Val D’or aren't distinct to Canada. Across the border in the U.S., African American and other women of color have suffered ongoing assaults by police, such as the high-profile case recently exposed in Oklahoma City. There, officer Daniel Holtzclaw, or “Claw” as his friends called him, abused African American women with impunity, most of them poor and suffering with substance abuse issues. He now faces up to 263 years in prison, though the actual penalty will be decided by a judge in early 2016.

Violence against minority women, whether committed by outsiders or members within their own communities, is often not reported by the victims – either out of fear that they won't be believed, or a desire to protect those they know. This experience is borne out by the stories of survivors, whether native and other minority women in Canada or predominantly, though not exclusively, African American women in the U.S. As Dr. Charlotte Pierce-Baker explained to Forbes magazine in 2012:

“We are taught that we are first Black, then women. Our families have taught us this, and society in its harsh racial lessons reinforces it. Black women have survived by keeping quiet not solely out of shame, but out of a need to preserve the race and its image. In our attempts to preserve racial pride, we Black women have sacrificed our own souls.”

Black Lives Matter – along with Native Lives Matter, which it inspired – brought much needed focus to the fatal shootings by police of mostly black men that have become an almost daily occurrence in the U.S. But that focus must be extended to the violence aimed at African American women from both inside and outside their communities. Whether in Canada or the U.S., women of color in North America have a long way to go before they see justice for the crimes committed against them. Let alone equality.

3 WAYS TO SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

- Log in to post comments